The Japanese economy is transitioning from a protracted deflationary environment to an inflationary one. As real wages continue to decline despite increases in nominal wages and tax revenues, the government faces new challenges, such as how to increase the take-home pay of the working generation and how to balance anti-inflation measures and fiscal consolidation. These challenges are beginning to manifest not only as issues of redistribution and taxation, but as distortions caused by healthcare financing.

This is because, even if wages increase thanks to anti-inflation measures and improvements in labor productivity, it will be difficult to increase the take-home pay of the working generation if social insurance premium contributions rise faster than wages.

◆◆◆

According to a long-term projection for the economy, public finance, and social security presented by the Cabinet Office at the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy on April 2, 2024, healthcare and long-term care insurance premium contributions as a percentage of gross domestic product could rise from 4.8% in FY2019 to 7.2% in FY2060. If these estimates are accurate, healthcare and other social insurance premium rates would have to be raised by about 50% by FY2060, greatly squeezing the take-home pay of the working generation.

Similar issues once occurred in pension financing in the past. Around 2003, the government estimated that if no reform was implemented, employee pension insurance premium rates would exceed 25% in the future. This estimate created strong opposition from the Japan Business Federation (known as Keidanren) and the Japanese Trade Union Confederation (known as Rengo), leading to a pension reform realized in 2004 in which the premium rate was fixed at 18.3% and inflation-indexed pension benefits were replaced with a macroeconomic slide mechanism to automatically adjust pension benefits.

This situation overlaps with recent concerns about growing social insurance premium contributions by the working generation, triggered by the Kishida administration’s unprecedented policy package which would secure resources to combat declining birthrates. Of the approximately 3.6 trillion yen in additional funding for the policy package, approximately 1 trillion is to be financed through an increase in medical insurance premium rates, which sparked criticism from business and labor interests.

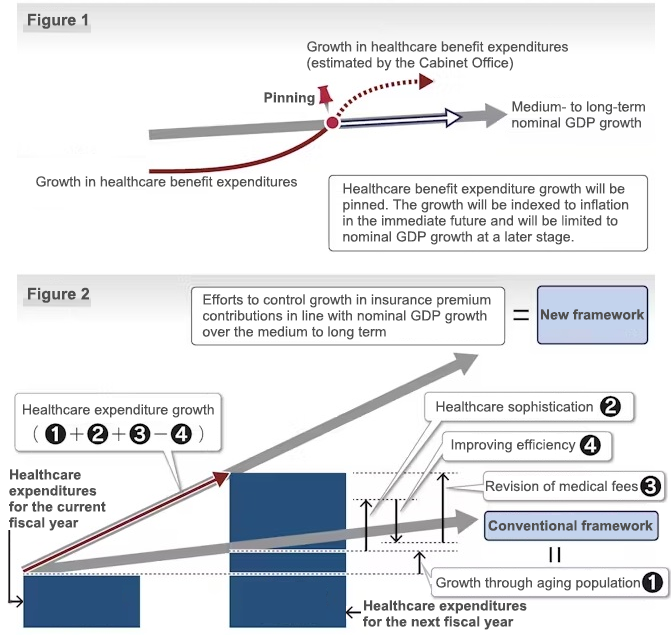

As a result, a footnote in the Children’s Future Strategy adopted by the cabinet in December 2023 called for a policy of minimizing premium rate increases to maximize take-home pay for young people and child-rearing households. This has the potential to lead to a healthcare-version of the macroeconomic slide mechanism (a healthcare expenditure growth adjustment mechanism), which would limit the long-term growth of total healthcare expenditures to within the range of nominal GDP growth (see Figure 1).

While total pension benefits are roughly controlled as a percentage of GDP under the macroeconomic slide mechanism, no such mechanism exists for the healthcare financing system.

From a macro perspective, however, the healthcare insurance premium rate equals healthcare insurance premium contributions divided by total employee compensation. Since healthcare insurance premium contributions are roughly proportional to healthcare benefit expenditures and employee compensation to nominal GDP, fixing the healthcare insurance premium rate will generally lead to keeping healthcare benefit expenditures within the range of nominal GDP growth over the medium to long term.

At first glance, the macroeconomic slide mechanism may be perceived as a draconian measure for the healthcare industry, but perceptions are changing as the economy shifts from deflation to inflation. In the initial FY2024 general account budget, healthcare expenditure growth after a medical fee revision stood at 1.0% for FY2024 and 0.8% for FY2025. Meanwhile, nominal GDP growth was forecast at 3.0% (estimated at 2.9%) for FY2024 and 2.7% for FY2025.

In other words, recent healthcare expenditure growth has been kept below nominal GDP growth. Healthcare expenditures as a percentage of GDP are likely to decrease for the second straight year. Behind this trend are an inflation rate above 2% and a slowdown in population aging. If this gap (about 2%) continues for 10 years, healthcare expenditures as a percentage of GDP may shrink by about 20%.

As a result of this inflation, growth in medical fees has failed to keep pace with healthcare institution expenditure growth, leading to a rapid increase in the number of deficit-ridden hospitals and growing calls for the improvement of the current healthcare expenditure system. In the future, in order to make healthcare sustainable, the introduction of a price indexation system for medical fees may become unavoidable.

On the other hand, if a price indexation system is introduced for medical fees, the ratio of healthcare expenditures as a percentage of GDP could continue to increase. If healthcare expenditure growth exceeds nominal GDP growth over the medium to long term, under the price indexation system for medical fees, a mechanism that can slightly reduce medical fee growth will be necessary to keep healthcare expenditure growth commensurate with nominal GDP growth over the medium to long term.

Since nominal GDP growth represents a combination of real GDP growth and inflation, a system which keeps healthcare expenditure growth in line with economic growth would incorporate inflation into healthcare expenditures, which would also benefit healthcare institutions.

◆◆◆

The specific adjustment method is as follows: Healthcare expenditure growth is determined by factors that increase healthcare costs (e.g., (1) population aging, (2) healthcare technology sophistication, and (3) revision of medical fees), as well as factors that improve efficiency (e.g., (4) effects of institutional reforms) (see Figure 2).

Consider a case for the annual average nominal GDP growth forecast at 3% (covering a real economic growth rate of 1% and an inflation rate of 2%) over the next several years. Here, let’s assume the upper limit of healthcare expenditure growth at Z=3%, and assume (1) equals 0.9%, and (2) equals 1%. Under this assumption, since the inflation rate is 2%, the revision rate for medical fees is set at +2% ((3)=2%) under the price indexation system for medical fees.

In this scenario, if institutional reform effects are small and represent a 0.5% reduction in healthcare expenditures (4), the projected healthcare expenditure growth will be 3.4% ((1) + (2) + (3) + (4)), exceeding the upper limit Z=3%. Therefore, the revision rate for medical fees must be adjusted to within Z.

Specifically, the price indexation rate for medical fees (2%) is reduced by 0.4 percentage points resulting in a final medical fee revision rate of 1.6% (3). Conversely, if institutional reform effects are large and represent a 1.2% reduction in healthcare expenditures (4), the projected healthcare expenditure growth will be 2.7%, which is 0.3 percentage points lower than Z=3%. In this case, the medical fee revision rate (3) is raised to 2.3% through a carryover adjustment to offset past reductions, aligning healthcare expenditure growth to the upper limit of Z=3%.

Since the actual revisions of medical fees occur every two years, it is important to consider a mechanism for automatic annual adjustments. There are also concerns that GDP will shrink if the population decline continues. Historically, however, the correlation between population and GDP is not particularly strong. While Japan’s population tripled in some 100 years from 1900, its GDP expanded more than 50-fold. The main sources of economic growth are productivity improvement and capital accumulation, meaning that economic growth can be achieved even under population decline.

The government’s traditional Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform, which provides guidelines for annual budget formulation, has controlled growth in healthcare and other social security expenditures based on population aging ((1) in Figure 2). However, with the slowdown in population aging combined with healthcare institutions’ anti-inflation measures and demands for wage increases among healthcare workers, this framework is gradually losing substance. As a new framework is required, a political decision to establish a forum for discussion within the government is desirable.

While some believe that the current inflation is temporary, changes in the global order, a reversal of economic globalization, and growing labor shortages in Japan suggest that inflation may not be temporary.

Japan’s real interest rates are negative, exerting downside pressure on the yen. Given the Japanese government’s massive debt and the impact on long-term interest rates, the Bank of Japan faces structural challenges in normalizing monetary policy, leaving various factors that could prolong an inflationary environment. The question is how to balance the sustainability of healthcare financing with excessive burdens on the working generation and anti-inflation measures.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

October 24, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun