To successfully implement the Regional Revitalization 2.0 initiative, which is one of the policy pillars of the Ishiba administration, it is necessary for the government to separate (i) demographic issues (including the stagnant fertility rate) from (ii) the issue of regional sustainability. The government must seriously address (ii) based on a strategy centered on “smart shrinkage,” on the premise of a shrinking population. Below, I will briefly explain the reasons for this approach.

The first point is the importance of squarely looking at data. The government is promoting the Evidence-Based Policy Making (EBPM) approach. Naturally, policies based on inaccurate data or misguided assumptions will not provide maximal benefits. To achieve intended goals, it is essential to determine policy targets based on accurate data. In this respect, there are two important datasets.

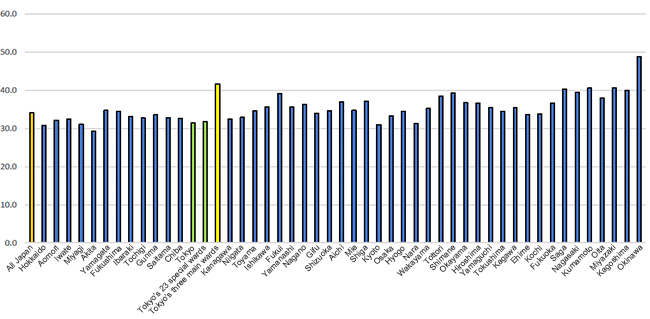

The average fertility rate in Tokyo’s three central wards is the nation’s second highest, following Okinawa

The first of the two important datasets is the birthrate data. In existing regional revitalization initiatives, the so-called “Tokyo Demographic Black Hole Hypothesis” (which maintains that the concentration of the young population in Tokyo, where the fertility rate is low, drags down the overall fertility rate in Japan) has been justification for efforts to lower the concentration of people in Tokyo. However, the potential of this hypothesis being flawed is starting to become clear when examining prefecture-to-prefecture comparisons of the demographic situation based on various fertility rate-related indicators.

It is true that when using total fertility rate (TFR) to compare prefectures, Tokyo tends to rank near the bottom; however, in terms of the average fertility rate (the number of births per 1,000 women of reproductive age, or women aged between 15 and 49 years old, including single women), its ranking rises.

[Click to enlarge]

The graph above shows the average fertility rate (the number of births per 1,000 women of reproductive age [between 15 and 49 years old]) by prefecture based on the Population Census (2020) data, providing evidence regarding the demographic situation in Tokyo compared with other prefectures.

Okinawa has the highest average fertility rate, at 48.9, followed by Miyazaki with 40.7. Meanwhile, Tokyo, with an average fertility rate of 31.5, is ranked 42nd among the 47 prefectures. Ranked just above Tokyo are Iwate (32.4), at 40th place, and Aomori (32.2), at 41st place, and ranked just below it are Nara (31.4), at 43rd place, Miyagi (31.1), Kyoto (31), and Hokkaido (30.8). At the bottom is Akita (29.3). What is interesting is that the average fertility rate in Tokyo’s three central wards (Chiyoda, Minato and Chuo Wards), at 41.7, is higher than the average values in all prefectures except Okinawa.

85% of young people who migrate to Tokyo do so when starting to work

The other important dataset is data on the demographics of the young population moving to Tokyo. While the media and some experts commonly state that young people come to Tokyo from other parts of Japan mainly for university, this is a misconception. That is immediately apparent from the Report on Internal Migration in Japan Derived from the Basic Resident Registration (2023). According to the dataset available from the report, the net population inflow into Tokyo in 2023 was around 58,000 people (38,000 people moved out of Tokyo and 96,000 people moved into Tokyo). Of the 96,000 people moving into Tokyo, only 14.5% were aged 15-19, while the share of people aged between 20 and 24 was 63.6%, and people aged 25 to 29 accounted for 21.8%. Those two age groups (people aged between 20 and 29) account for as much as 85.3% of the total inflow.

Given that the typical age of university enrollment is 18 and the typical starting age of work is 22 or 23, it is clear that young people come to Tokyo mainly to start careers, rather than for university, as is widely assumed. The data readings are also consistent across genders: for males, 13.9% of the influx was aged 15-19, while 86% were in the 20-29 age bracket; for females, the 15-19 age bracket represented only 15.1% and 84.6% were aged 20-29. In fact, examining the data from the Basic School Statistics (FY2023), among students enrolling in universities inside Tokyo, approximately 70% are from Tokyo and three neighboring prefectures and 80% are from the broader Kanto region.

With the ongoing population shrinkage, it is important to promote the compact city approach in view of the relationship between the economic growth rate and population density. I do not in principle support the idea of restricting population inflows into urban areas because such restriction would have a negative impact on the economic growth rate. However, if the government earnestly hopes to restrict the inflow of young people into Tokyo, it is necessary to consider how to curb youth migration to Tokyo at the start of their working career, rather than at the time of university enrollment.

Importance of the “smart shrinkage” strategy premised on a shrinking population

According to the National Grand Design 2050, published by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in 2014, it is projected that by 2050, 60% of Japan’s land area will be subject to population declines of over 50% from 2010 levels, or become uninhabited. It is necessary to come to the sober realization that halting population decline through the regional revitalization initiative and measures to raise the fertility rate will not be an easy task. In fact, following the launch of the regional revitalization initiative in 2014, the total fertility rate declined for eight straight years, from 1.45 in 2015 to 1.20 in 2023, and the regional revitalization initiative has yet to produce any observable effect on the fertility rate.

As the situation indicates, the disappearance of several cities is inevitable. Therefore, a shift to a smart shrinkage policy based on the premise of population decline is imperative. Regarding the smart shrinkage strategy, a report (June 2008) by the Study Group on Future Framework of Urban Area Development under the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, is one early example where the importance of measures to “smartly shrink” urban areas was mentioned. The report recommended “inducing land use transitions, including converting urban areas into ‘green spaces,’ including forests; ‘farmland,’ including cultivated areas and plots for citizen farms; and ‘residential areas,’ including new types of suburban housing adapted to purposes such as dual-location living, in order to prevent the areas from falling into decay, while maintaining their public services to some degree.” More than 15 years have passed since the issuance of the report, and its principles remain urgent and relevant today. To successfully implement the Regional Revitalization 2.0 initiative, it is necessary to separate (i) demographic issues (including the stagnant fertility rate) from (ii) the issue of regional sustainability. The government must then seriously address (ii) above by thoroughly promoting smart shrinkage strategies including the compact city approach and other related initiatives in order to create a sustainable future.

November 19, 2024

>> Original text in Japanese