In Japan, the population shrinkage and aging of society coupled with a low fertility rate are continuing at a tremendous pace. In 2030, the proportion of people who are aged 50 or older among the total number of eligible voters is set to exceed 60%. This is the first case in human history of a democracy experiencing such a situation. There are also concerns that the difference in the weight of each vote between urban and rural areas may widen further and that the rise of a “gray haired democracy” may accelerate. Under these circumstances, over the past 10 years or so, various arguments have emerged in relation to voting rights and election systems.

To redress the advance of the gray-haired democracy through election system reform, proposals have been put forward for adopting a generation-by-generation electoral constituency system, which allocates parliamentary seats across generations, rather than across geographic districts, in accordance with each generation’s share in the voter population; and a life expectancy voting system, which allocates seats across generations in accordance with each generation’s remaining life expectancy. The “voting rights for newly born babies” concept, which has recently attracted media attention after being mentioned by some politicians, is another proposed option.

This last concept is formally known as “Demeny voting,” after the Hungarian demographer who proposed it, Paul Demeny. Under the Demeny voting system, children, including newly born babies, are granted voting rights under the assumption that their parents vote as their proxies. In many cases, those who advocate this system propose splitting by half the voting right granted to each child and allocating them between the parents. In Hungary, there was a proposal for giving an additional one vote to the mother.

While some people criticize Demeny voting for contravening the principle of one vote for one voter by granting extra votes to parents as proxies, from Demeny’s perspective, the more substantial problem was the absence of voting rights for children, who constitute a substantial portion of the population. The essence of Demeny voting is, first and foremost, granting a voting right to each child, including newly born babies, as the ultimate form of the lowering of the eligible voting age under the principle of one vote for one voter. With that in mind, Demeny voting should be understood as a voting system which allows parents to cast a proxy vote when children themselves cannot vote.

Regarding proxy voting, a system which allows proxy voting on behalf of elderly people with dementia, in fact exists, for example. The proxy voting issue requires dispassionate discussion, including addressing consistency with and the actual situation of existing cases of proxy voting like the aforementioned case.

◆◆◆

Historically, democracy has developed with the expansion of suffrage. In Japan’s first democratic election with limited suffrage (held in 1890), only men aged 25 or older who paid at least 15 yen in direct national tax (at the time accounting for 1% of the population) were allowed to cast a vote. As suffrage gradually expanded, all men aged 25 or older were in principle granted the right to vote in 1925. However, women continued to be excluded from the electoral process throughout the prewar period.

It was not until 1945, after the end of World War II, that universal suffrage for men and women was introduced in Japan, with the eligible voting age lowered to 20 years old. In 2015, the voting age was lowered further, to 18 years old.

Outside Japan, there are countries where the eligible voting age is 16 years old (e.g., Australia, Brazil, and Argentina). It is therefore quite natural to ask why the eligible voting age cannot be lowered even further. Is it really not possible to lower the age limit to 15 years old, or 10 years old, for example? The “voting rights for newly born babies” concept is an extension of that fundamental question.

What becomes a point of contention here is how this matter is related to the Constitution. Article 15, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution stipulates the following: “Universal adult suffrage is guaranteed with regard to the election of public officials.” The issue is what the word “adult” here means.

A reference document prepared by the Research Commission on the Constitution of the House of Representatives states the following: “There are arguments as to what the term “adult” means under the Civil Code… In either view, the Constitution merely guarantees suffrage for adults and does not prohibit suffrage from being extended to other persons.” In short, the possibility of extending suffrage to those who are below the age of 18 has not been rejected. The Ministry of Justice’s “Final Report on Lowering of Adult Age under the Civil code” includes a similar observation.

More interestingly, outside the scope of national elections, there have been cases where suffrage was extended to those who were below the age of 18 in local referendums. For example, some underage children were granted the right to cast a vote in three local referendums that were held in 2003 on whether or not to approve the merger of municipalities: the voting age limit was lowered to the fifth grade in a referendum in Naie Town, Hokkaido and to the seventh grade in referendums in Hiraya Village, Nagano Prefecture, and Mitsuse Village (now part of Saga City), Saga Prefecture.

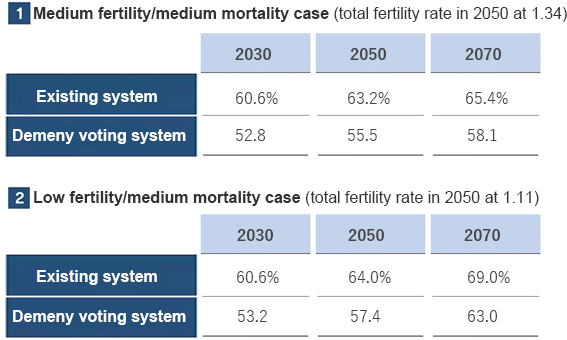

How will the proportion of people aged 50 or older in the total number of eligible voters change by 2030, 2050, and 2070 if the “voting rights for newly born babies” concept is put into practice? (see the table below).

According to calculations based on the Population Projections for Japan (2023), prepared by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the proportion of people aged 50 years or older in the voter population is projected to be 60.6% in 2030 in a medium fertility/medium mortality case under the existing voting system with the voting age limit of 18 years old. The figure is projected to rise to 63.2% in 2050 and to 65.4% in 2070.

If suffrage is extended to children, including newly born babies, the proportion of people aged 50 or older would decline to 52.8% in 2030. The figure would remain below 60% until even later, at 55.5% in 2050 and at 58.1% in 2070.

According to the Public Opinion Survey on the Life of the People (November 2023 Survey), conducted by the Cabinet Office, people in the age group of 18 to 39 years old place a high priority on employment and education as policy challenges. On the other hand, people aged 60 years old or older place high priority on pensions, healthcare, and measures to address problems related to an aging society. If the proportion of elderly people in the voter population changes, the political platforms advanced by candidates (election strategies) are also expected to change.

◆◆◆

There is also an argument that the introduction of Demeny voting could improve the fertility rate. Although this possibility cannot be dismissed on theoretical grounds, nobody knows how effective Demeny voting would be in raising the fertility rate because no real-world cases of its introduction yet exist.

Nevertheless, there is an important perspective that the political influence of households with children will grow if Demeny voting is implemented, and the effects of this will vary from region to region

Many people are of the opinion that in order to raise the fertility rate, it is necessary to improve the childcare environment in urban areas. The situation in Tokyo is a case in point. Although Tokyo has the lowest total fertility rate of Japan’s 47 prefectures, a different picture appears if we look at the situation by another measure of fertility.

In terms of the average fertility rate (the number of children that are born to every 1,000 women who are of reproductive age, that is, who are in the age group of 15 years old to 49 years old, including unmarried women) by prefecture, calculated on the basis of the 2020 Population Census data, Tokyo, with a rate of 31.5, is in the 42nd position, up from the very bottom of the ranking table. If we focus on the downtown business area of Tokyo (Chiyoda, Minato and Chuo Wards), the change is striking: the average fertility rate in that area, at 41.7, would be the nation’s second highest (after the rate of 48.9 in Okinawa).

The number of births is higher in urban areas than in rural areas, where the proportion of elderly people is relatively large. If Demeny voting were introduced and consequently the childcare environment improved in urban areas, where there is a higher concentration of younger people, it may be possible to curb, to some degree, the pace of the decline in the number of births.

Regarding election systems, there are also arguments over whether to lower the age limit for candidates. The interests of future generations who have yet to be born are also important. Apart from election system reform, there are other possible ways of inducing voters to make rational decisions that incorporate intergenerational interests. Japan should consider establishing an independent fiscal institution that is responsible for making long-term fiscal projections and publishing generational accounting analysis, modelled on the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and the UK.’s Office for Budget Responsibility.

José Ortega y Gasset, a Spanish philosopher, argued as follows in his book The Revolt of the Masses. A democracy’s soundness is affected by a single trivial technical detail regardless of its form or degree of development. That detail is the election procedure. Other matters are secondary. If the election system is appropriate and is aligned with reality, everything will go well. Otherwise, everything will go badly even if other matters turn out to be ideal.

A super aging society is about to arrive. Resolving fiscal problems and intergenerational inequity will become more and more important. Now is the time to start in-depth discussions in earnest on the vision of an ideal democracy that lays the foundation for decision-making.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

Augusut 30, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun