In early October 2023, the Reiwa People’s Council (popularly known as Reiwa Rincho), which was established by Mogi Yuzaburo, Kikkoman’s honorary CEO and chairman of the board, and others, compiled and announced a proposal paper titled “Toward Realization of Fiscal Management for Creating a Better Future—Establishment of a Long-Term Fiscal Projection Committee and a Policy Program Evaluation Committee.” The proposed long-term fiscal projection committee is equivalent to an entity known in other countries as an independent fiscal institution (IFI). I also proposed the establishment of an IFI in one of my book, Restructuring of the Japanese Economy (written in Japanese, Nikkei Publishing Inc.), and other publications that came out more than 10 years ago.

Establishing an IFI is important because reducing fiscal deficits is politically rather difficult. Political factors that may generate fiscal deficit include (1) the political business cycle, (2) politicians’ strategic motives, and (3) the common resource problem. Of the three, the common resource problem is considered to be the most potent factor.

Generally speaking, the common resource problem refers to the tendency of publicly shared resources to be overly used compared with privately owned resources. The “tragedy of the commons,” which represents the worst case of the commons resource problem, has become quite well-known as a phenomenon of common resources being entirely depleted due to excessive use. In the case of fiscal management, fiscal transfer policy is by nature a zero-sum game, and therefore, if fiscal expenditure is increased, ultimately, someone (including future generations) will be made to bear the cost of fiscal expansion.

However, as individual agents’ benefits and costs are not necessarily linked to each other in a clear-cut manner, cost awareness tends to be weak. As a result, the phenomenon of growing political demand for increasing fiscal expenditure resulting in fiscal deficits is becoming more common. This is exactly the fiscal equivalent of the tragedy of the commons.

In any case, political actions seem to create significant pressure in the direction of larger fiscal deficits. Some studies have pointed out that if the fiscal authorities, including the Japanese Ministry of Finance, had actually possessed greater authority, it is possible that the fiscal situation would not have deteriorated to the levels that we now see in Japan and other countries. Therefore, in order to control political pressures, the development of fiscal policy rules has been promoted, particularly in the United States and Europe in the 1990s (depoliticization of fiscal policy). This initiative has been successful in some countries, as shown by the fiscal consolidation achieved in Canada and Australia. However, as fiscal management is closely interconnected with economic cycle projections, it is rather difficult to control it with simple fiscal rules. Conversely, if overly flexible and lenient rules are set, the objective of restraining political pressures toward the creation of fiscal deficits cannot be achieved.

Therefore, since the 2000s, debate on whether or not to establish an IFI equipped with a high level of professionalism and analysis capability for the purpose of resolving such problems has become livelier, mainly in Europe. An IFI is supposed to be given a degree of political independence and be charged with responsibilities such as (1) making economic projections that form the basis of budgeting, (2) conducting fiscal estimation, and (3) evaluating fiscal policy.

Among existing IFIs, the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis (established in 1945) and the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) (established in 1974) are well-known as institutions with long histories. Since 2000, IFIs have continually been established in OECD countries, including the U.K. Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) (established in 2010), the Swedish Policy Council (established in 2007), the Canadian Parliamentary Budget Officer (established in 2008), and the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (established in 2011).

Although it is therefore also important to establish an IFI in Japan, it may be necessary to hold more dispassionate discussion on whether or not doing so will actually contribute to earnest efforts toward fiscal consolidation. That is because the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy under the Cabinet Office already compiles the Economic and Fiscal Projections for Medium to Long Term Analysis report twice each year—although the projections are relatively short-term compared with the ones made by typical IFIs—and announces the primary balance (PB) and fiscal balance (FB) projections for the next 10 years that cover both the national and local governments.

In the most recent version of this report, published in July 2023 by the Cabinet Office, the baseline case projection of fiscal deficit as a proportion of GDP in FY2032 is 1.3%. The convergence value of the outstanding amount of debt as a proportion of GDP calculated based on Domar's proposition (Note 1) and the average growth rate of nominal GDP between FY1995 and 2022 (0.35%) comes to approximately 371% (=1.3÷0.35). This suggests the possibility that the outstanding amount of debt as a proportion of GDP will expand further from the current level (approximately 210%), but there are no signs of efforts toward fiscal consolidation beginning in earnest.

What is the cause of the lack of action toward fiscal consolidation? There is a host of factors, one of which is the absence of a system of ex-post review of governmental projections. The fiscal deficit projections and the primary balance as a proportion of GDP published by the Cabinet Office as part of the medium- and long-term economic and fiscal projections are too optimistic in the first place.

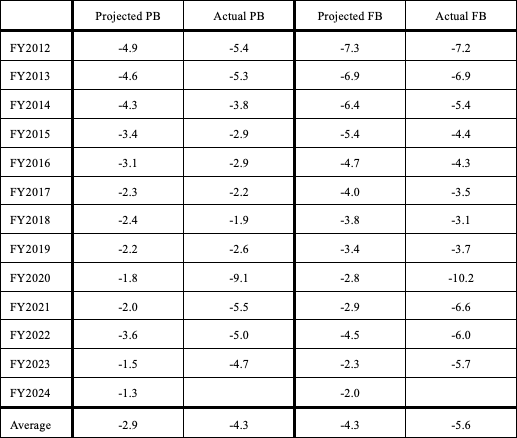

That is obvious from the table below. The table shows the projections presented by the Cabinet Office in the Economic and Fiscal Projections for Medium to Long Term Analysis (baseline case) and the actual fiscal balance. Since FY2019, the deviation of the projection from the actual balance has expanded. If this trend continues, the most likely scenario is that it will become difficult to turn the primary balance to surplus in FY2025, with the outstanding amount of government debt as a proportion of GDP continuing to grow.

While the average projected deficit is 4.3% as a proportion of GDP as shown in the table, the average actual deficit is as high as 5.6%. If the assumed average growth rate of nominal GDP is set at 1.4%, four times as high as the average in the past (0.35%), under Domar’s proposition and if the fiscal deficit is fixed at 5.6% as a proportion of GDP, the convergence value of the outstanding amount of debt as a proportion of GDP comes to 400%.

The government has maintained the goal of turning the primary balance to surplus in FY2025. At a meeting of the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy on July 25, 2023, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida stated that if appropriate economic fiscal management and expenditure reform continues, the possibility of turning the primary balance, including the balances of the national and local governments to surplus, will come within sight. If the goal of turning the primary balance to surplus is achieved, it will certainly mark the first step toward fiscal consolidation. However, if additional government bonds are issued and if the government continues to compile supplementary budgets and implement tax cuts every year, it will become impossible to achieve the primary surplus goal. Analyzing and explaining the factors that caused the fiscal projections to deviate from the actual results to the people will be the first step toward fiscal consolidation in the true sense of the word.