Many people are concerned that the economic policies of the second U.S. Trump administration, or Trump 2.0, may have a negative impact on the Japanese economy. Whatever happens with Trump 2.0, however, two points are clear.

One is that the United States will continue to be the center of the world’s advanced technologies for decades to come. The other is that emerging and developing “Global South” countries will have a larger share of the global economy. India’s gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to become the third largest in the world by 2028. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) will have a similar economic size, and Japan should deal with Trump 2.0 based on these two realities.

◆◆◆

First of all, Japan should maintain and expand its knowledge network with the United States irrespective of any decrease in U.S.-bound exports, as long as the United States remains the center of advanced technologies. According to our study, inward and outward foreign direct investment accompanied by international research greatly improves Japanese companies’ innovation capabilities and productivity. Expanding the knowledge network is important because technological progress is the ultimate source of economic growth.

However, Japan’s international joint research has been sluggish. The share of patents from international joint research in Japan is the second lowest among major countries. In contrast, China has taken advantage of joint research with developed countries to achieve high economic growth. In recent years, however, U.S.-China joint research has been rapidly shrinking due to their bilateral political confrontation. This trend is accelerating, providing room for the expansion of Japan-U.S. joint research.

Therefore, it is reasonable for the Japanese government to have adopted a new industrial policy to support Japanese companies’ joint research with their counterparts from friendly countries, such as the United States, in the semiconductor industry.

For example, Rapidus Corp., a government-backed Japanese semiconductor company, is collaborating with foreign companies and research institutes such as International Business Machines Corp. (IBM) and the U.S. National Center for Semiconductor Technology (NSTC). Taiwanese semiconductor giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. (TSMC) has set up an R&D base in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture, with support from the Japanese government, and is collaborating with many Japanese companies and universities.

Such international collaboration can bring new technologies to each participating country and be a catalyst for economic growth. "Knowledge friend-shoring" to expand intellectual cooperation with friendly countries in semiconductor and other fields must become a priority for Japan under Trump 2.0.

As it is difficult for companies to find suitable foreign joint research partners on their own, government policy support is required. Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of government support in matching between companies through international exhibitions and trade fairs. Recently, the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) announced that it will partner with a U.S. semiconductor research facility operator to support joint research between Japanese and U.S. companies. Future industrial policy should not only provide subsidies, but also strengthen support for such business connections.

Trump 2.0 is also expected to expand restrictions on technology transfers for national security reasons, becoming an obstacle to joint research between Japan and the United States. In order to prevent such a development, Japan’s public and private sectors should work together to explain and demonstrate to the U.S. government that joint research with Japan is in the interests of the United States.

In order for Japanese companies to benefit in a way that is acceptable to the Trump administration in Trump 2.0, Japanese companies should make direct investment in the United States, establishing both R&D and production bases there. If high tariffs are imposed, Japanese companies may have to relocate production bases to the United States to some extent. Japan should invest in R&D while relocating production bases to bring U.S. advanced technologies to Japan.

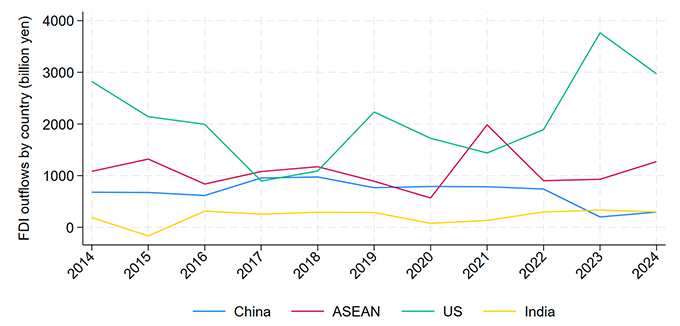

However, it should be noted that Japanese manufacturing investment in the United States stagnated under Trump 1.0 between 2017 and 2021 (see the chart). Under the subsequent Biden administration, as a consequence of the U.S.-China divide, Japanese companies reduced investment in China while increasing investment in the United States. This trend should not be halted.

(Manufacturing industries)

Trump has indicated that he will oppose the acquisition of United Steel Corp. by Nippon Steel. It is a foregone conclusion that greenfield investments that create new business bases in the United States are more likely to gain easy approval under Trump 2.0, rather than mergers with or acquisitions of U.S. companies.

One good example is TSMC’s new manufacturing base in Arizona which has attracted increased investment by Japanese companies in the surrounding area. Japanese companies are also participating joint semiconductor-related research led by Arizona State University. It is hoped that industry and government sectors will work together to increase R&D-related investment in the United States and deepen their win-win relationship.

◆◆◆

Expanding sales channels to the rapidly emerging Global South will also be essential for Japan under Trump 2.0. As the risk of disruptions to supply chains with China is increasing, it is necessary for Japanese companies to transfer their production and procurement operations to the Global South to some extent.

However, Japanese companies’ expansion of supply chains to the Global South has made little progress due to the various barriers in place, and the level of Japan’s direct investment in manufacturing in ASEAN and India has remained mostly unchanged from the 2016-2018 period before the current U.S.-China trade tensions to between 2022 and 2024 after the COVID-19 disaster (see chart).

One of the reasons for the stagnation is competition with China. The Global South has not sided with the West politically or economically, seeking to benefit from dealing with both the United States and China in a balanced manner.

Moreover, China has provided infrastructure and economic benefits to the Global South through its Belt and Road Initiative. In contrast, the United States, which leans toward protectionism, has not opened its market sufficiently to the rest of the world. From that perspective, it is understandable that many emerging and developing countries are enhancing their relations with China.

Japan must work with other Western countries to deepen ties with the Global South through infrastructure assistance and technical cooperation. Multilateral frameworks, such as the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) initiative, and official development assistance (ODA), whose flexible operation has become possible, will prove useful to this end.

There are other major challenges in expanding supply chains to the Global South. Western countries are urging Global South countries to abide by democratization, human rights, and environmental standards that are on par with those in developed countries. From the end of 2025, the European Union will require palm oil and cocoa producers to prove that their exported products are not the cause of deforestation. Indonesia and Malaysia are strongly opposed to the imposition of such standards.

Data for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries clearly demonstrate the tendency for trade to decline with greater differences in democratization and economic freedom between trading countries. In that sense, institutional differences are an obstacle to developed countries’ economic relations with the Global South.

Japan, as a country located in Asia that developed later than Western nations, has a deeper understanding of the realities facing the Global South than the West. Japan should become a bridge between the West and the Global South by tolerating incremental improvements in areas such as democratization and environmental regulations.

Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba will visit Indonesia and Malaysia in early 2025. About 70 years ago, in 1955, Indonesian President Sukarno organized the Asian-African Conference (Bandung Conference) which advocated unity through peaceful coexistence, with participation by developing countries of the time.

I hope that the Japanese government will take this opportunity to propose a “New Bandung Consensus” which will set out the direction of institutional reform in line with the realities of the Global South. Trump 2.0 may be more flexible to institutional differences, and we should explore opportunities for Japan and the United States to cooperate to win the trust of the Global South.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

December 26, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun