Global supply chains are undergoing change. One reason is that Japan, the United States and European countries have been restricting trade and investment relationships with China since around 2019, as they have recognized the security risks involved in their relationships with that country.

In recent years, in order to disconnect supply chains for key products, such as semiconductors, from China and increase supply chain resilience, Japan, the United States and European countries have used huge amounts of subsidies to promote efforts to bring production facilities back to their home turf (onshoring). The Japanese government earmarked a total of 620 billion yen as financial aid under the FY2021 supplementary budget to encourage TSMC, a major semiconductor manufacturer in Taiwan, to build a factory in Kumamoto Prefecture in southwestern Japan and to undertake other similar initiatives. The Japanese government has also provided around 520 billion yen in subsidies for domestic capital investments in order to reduce the risk of supply chain disruption in high-tech industries.

This article provides an overview of changes in supply chains, offers evaluation of policy initiatives that support onshoring and presents relevant proposals.

◆◆◆

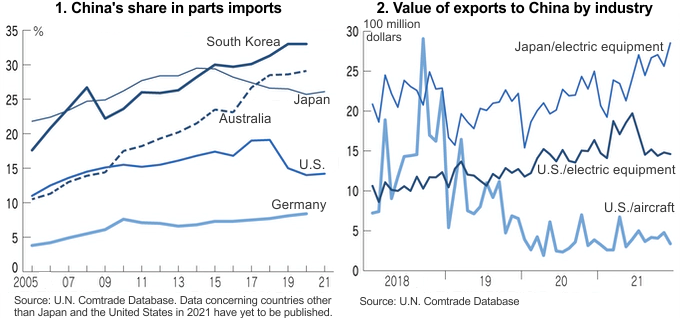

For some time, as Japanese firms' supply chains have depended heavily on China, they have faced a serious risk of supply disruption. Data on China's shares in other countries' parts imports show that the share in Japanese parts imports hit a record high of around 30% in 2014 but it has continued to decline since 2015 (see Figure 1). The Chinese share in U.S. parts imports has also decreased steeply since 2019. However, South Korea, Australia and Germany have become increasingly dependent on imports from China.

On the other hand, the total value of exports from Japan and the United States to China has increased steeply over the past three years. Even exports of electronics and electrical products from both countries have increased. (see Figure 2). Among the few products whose exports to China have declined are aircraft and some semiconductor-related products, such as dry-etching equipment, from the United States.

Supply chains become more resilient if they are more geographically diversified. That is because geographical diversity makes it easier to switch to an alternative supply source country when a pandemic or a natural disaster causes disruptions in supply from a certain country. That has been confirmed by the results of studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including our analysis based on firm data collected by the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA).

While reducing their dependence on China, diversifying parts supply sources, and cutting back on exports of strategically critical items to the country, Japan and the United States have increased overall trade with China. That is a favorable trend from the viewpoints of enhancing supply chain resiliency and promoting economic growth.

Policy initiatives are contributing to this trend. In the case of Japan, whose dependence on China in terms of imports has declined since 2015, there is another major factor, that is, a change in Japanese firms' risk perceptions due to the intensified anti-Japan protest movement following Japan's nationalization of the disputed Senkaku Islands in 2012.

However, as Japan also still continues to depend heavily on China, it must promote diversification further in order to develop resilient supply chains. To do that, some policy initiatives are essential, but the currently implemented policy initiatives have some problems.

First, if onshoring of supply sources goes too far, supply chains could become vulnerable rather than resilient. In Japan, which is a country prone to natural disasters, the risk of domestic supply chain disruption is high. This risk can be reduced by dispersing supply chains internationally.

In addition to the support for onshoring, the government is providing subsidies for the transfer of production facilities to ASEAN countries, and this is desirable from the viewpoint of enhancing supply chain resiliency. Moreover, public organizations, such as the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), have been providing information that is useful for overseas business expansion and supporting the development of networks through business matching. There is much evidence to indicate that those support measures are effective, so they should be further utilized to promote the diversification of supply chains.

Second, it is doubtful whether using subsidies to encourage the construction of production facilities in Japan will revive the domestic semiconductor industry. In the past, there was a similar measure, that is, a subsidy program to encourage the construction of high-tech industry production facilities in provincial areas. However, according to Keio University Professor Toshihiro Okubo and his colleagues, policy initiatives implemented in the 1980s and 1990s to promote research and development (R&D) and other intellectual business activities ended up attracting low-tech industries in many cases. That is because innovative firms are unwilling to move away from dense industrial clusters where technology and information are accumulated, even if subsidies are offered.

A similar problem has occurred in the case of the effort to encourage TMSC to build a factory in Kumamoto. The factory planned by TMSC is expected to manufacture commodity semiconductors, rather than state-of-the art chips. That is unlikely to lead to advanced industrial development.

Third, it is also doubtful whether "industrial policy" as narrowly defined, that is, policy focusing on supporting a particular industry, such as semiconductors, can produce positive effects. Industrial policy is attracting renewed interest globally. One reason is the rapid growth of China, which is implementing industry-supporting programs on a massive scale. However, according to University of Tokyo Professor Tomoo Marukawa, China's industrial policies are a series of failures. Even the program to support the semiconductor industry has not necessarily been successful, with the domestic production ratio falling far short of the government's target.

A study by Philippe Aghion of INSEAD and his coauthors, which used data for Chinese firms, found that industrial policy improved firms' productivity only when competition was maintained within the supported industry. In other words, it may be said that China’s high-tech industry's rapid growth has essentially been driven by intense competition between private-sector companies although industrial policy may have made some contributions.

Therefore, going forward, industrial policy should be devised so as to encourage the exercise of ingenuity in the private sector by promoting competition in a broad range of industries, rather than focusing on a particular industry, as has been argued by Harvard University Professor Dani Rodrik.

I do not deny that semiconductors are strategically important. However, it is not necessary to keep the full range of production processes, including design and production of materials and manufacturing equipment, within Japan. That is because the risk of supply disruptions lasting for an extended period of time on a large scale is small so long as supply chains are located in countries that do not pose a security risk.

Furthermore, thanks to their cutting-edge technological prowess, Japanese firms have large global shares of some important production processes, and Japan has some degree of influence over the semiconductor supply chain. Making more Japanese firms globally competitive not only in the semiconductor industry but in a diverse range of industries will continue to be critical for both economic growth and supply chain resiliency.

◆◆◆

Providing policy support for R&D and intellectual partnerships is effective in strengthening competitiveness. That is because the benefits of R&D and intellectual partnerships proliferate throughout society, as was observed by Paul Romer, laureate of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Providing massive support for R&D will be the second pillar of U.S. and European plans to strengthen supply chain resiliency, along with encouraging onshoring of supply chains. On that point, Japan should follow the example of the United States and Europe.

As part of its support for the semiconductor industry, Japan is also assisting intellectual partnerships. In 2021, TSMC established an R&D center in Tsukuba City, Ibaraki prefecture. In addition to the provision of subsidies by the government, the establishment of a framework for partnerships with Japanese firms and universities under the leadership of the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) served as an inducement for TSMC to set up R&D operations in Japan.

Our empirical research has shown that encouraging foreign firms to establish R&D centers in Japan and promoting joint research with foreign firms in that way helps improve Japanese firms' technological prowess significantly. Firms can learn about each other's technologies through international partnerships. Therefore, the government should encourage foreign firms to establish R&D centers in Japan and support intellectual partnerships between Japanese firms and universities and their foreign counterparts in a broad range of industries. However, when undertaking these measures, it is essential to avoid national security risks, so it is desirable to use international frameworks that Japan has formed with countries that pose little national security risk, such as the Free and Open Indo-Pacific initiative and the QUAD group, which brings together Japan, the United States, Australia and India.

Only if Japanese firms and individuals make successful use of policy initiatives under such governmental support to keep connected with the world and engage in constructive competition can Japan's economic growth be achieved, and supply chain resiliency be enhanced.

When confronted with economic shocks, the government tends to adopt an isolationist policy as people cast a wary eye toward other countries as possible sources of the shocks. After the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, the government implemented many policy measures intended to promote economic growth driven by domestic demand, but those measures ended up prolonging Japan's economic stagnation. This time around, the government should overcome the current crisis without leaning towards an isolationist policy.

* Translated by RIETI.

March 9, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun