In recent years, the risk of global supply chain disruption has grown due to national security problems, COVID-19, and natural disasters. To address the growing risk, large-scale policy measures have been implemented, raising the possibility that global supply chains may be drastically reorganized in the future. With this situation in mind, the author published a RIETI policy discussion paper titled “Resilient and Innovative Supply Chains: Evidence-based policy and managerial implications,” in which policy and managerial suggestions related to global supply chains are presented. This article is a summary of that paper.

What Are Resilient and Innovative Supply Chains?

What are resilient and innovative supply chains? On this point, many researchers, including the author, have conducted empirical analyses from various angles. As a result of those analyses, it has been found that when suppliers are dispersed and diversified across countries, the impact of a disruption in supply of products or parts from a certain supplier can be minimized, by sourcing from alternative suppliers (Kashiwagi, et al., 2021; Todo, et al., 2021).

Moreover, geographically diversified supply chains make it possible to obtain new technology, knowledge and information from foreign partners, and in that sense, they are more innovative than undiversified ones. Many studies have empirically shown that imports and exports as well as inflows and outflows of foreign direct investments bring productivity improvements. In the case of domestic supply chains in Japan, companies doing business with suppliers and customers outside their own regions have higher total sales and sales per employee and file more patent applications than those which concentrate on business transactions within their own regions (Todo, et al. 2016).

In addition to supply chains, networks of enterprises linked through transactions of materials and parts, and knowledge networks, such as research collaboration networks, are quite helpful for learning and innovation (Iino, et al., 2021).

Current Situation of Global Supply Chains

Let us look at the current status of policies related to global supply chains and international knowledge networks from the viewpoints of resilience and innovativeness.

Since 2018, the United States has implemented trade and investment policies that seek to decouple the U.S. economy from the Chinese economy in the high-tech sector due to national security concerns. More recently, it has started large-scale policy assistance for the purpose of strengthening supply chains in the semiconductor industry. Japan and European countries have followed suit in providing similar policy assistance. China reacted to those policy moves by imposing restrictions on trade and investments in Chinese enterprises, providing massive assistance for the high-tech industry, and strengthening controls of Chinese technologies.

However, despite those policy moves, the volumes of China’s trade with Japan, the United States and Europe have not necessarily declined. Rather, trade volumes have been trending slightly upward since the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. Trade shrank only in terms of exports of some semiconductor-related items from the United States to China.

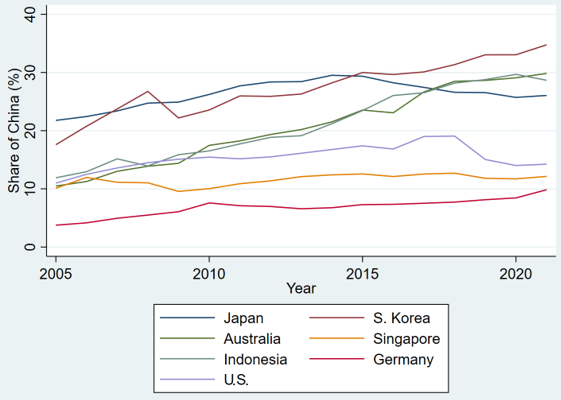

In fact, many countries’ dependence on China for imports of parts—that is, China as a supplier—has continued to increase for the past 10 years or longer, while Japan’s and the United States’ dependence has been on a downtrend, since 2015 in the case of Japan and since 2018 in the case of the United States (see the figure below). In other words, Japan and the United States have lowered the risk of supply chain disruption without losing benefits from trade, and this trend is favorable for economic growth and supply chain resilience.

However, China’s share of imports by Japan is still high compared with the share of imports by the United States, Singapore and Germany (see the figure above). In particular, the Chinese share in Japanese imports of electrical and electronic equipment is around 50%, while the Chinese share in Japanese imports of auto parts is around 40% and has continued to rise in recent years.

As for the current status of international knowledge networks, Japan has lagged far behind in internationalization of research and development activity. For example, the share of international co-inventions in all patent applications during the period from 2012 to 2015 was 1.3% in Japan, much smaller than the shares of 3.6% in South Korea, 5.7% in China, and 10.0% in the United States (OECD, 2017). According to the OECD, 2021, Japan ranked 15th for the number of biomedical publications related to COVID-19 and 18th for the number of publications written in international collaboration. This sluggishness in international research collaboration is a factor behind the prolonged stagnation of the Japanese economy.

First, the Japanese government and companies should aim for internationalization of supply chains, rather than onshoring/reshoring of production operations to Japan. Many policies implemented in recent years have been intended to bring supply chain operations to Japan by offering subsidies. The Japanese government is assisting investment in Japan by TSMC, a Taiwan-based major global semiconductor manufacturer, using a subsidy of around 620 billion yen. However, large-scale onshoring/reshoring runs counter to the internationalization of supply chains and heightens the risk of supply chain disruption. In particular, Japan is prone to natural disaster risks, and supply chain disruptions caused by a natural disaster in the country are likely to have a huge impact. Onshoring/reshoring also significantly undermines economic efficiency.

Therefore, policies should not focus exclusively on onshoring/reshoring of supply chain operations to Japan. They should focus more on the geographical diversification of supply chain partners across national borders while reducing dependence on China. However, this effort should aim for “friend shoring,” that is, expanding supply chain operations to countries that do not pose national security concerns. To that end, support for information sharing and business matching initiatives to promote overseas business expansion should be provided, using international frameworks among friendly countries, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF), the QUAD group, which is comprised of Japan, the United States, Australia and India, and the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI), which brings together Japan, Australia and India.

Second, industrial policy targeting a specific industry is not necessarily effective. In recent years, industrial policy has in many cases targeted a specific industry, the semiconductor industry in particular. Such targeting has come to be favored by policymakers at a time when economists are beginning to re-evaluate the effectiveness of industrial policy. However, economists who are re-evaluating industrial policy have negative opinions about the kind of traditional industrial policy in which the targeted industry is determined by the government under a top-down policymaking approach (Aiginger and Rodrik 2020). One empirical study has shown that China’s industrial policy was effective only when competition between companies was ensured (Aghion et al. 2015). Therefore, at the very least, an industrial policy targeting the semiconductor industry should be implemented together with policy measures to promote openness and competition. One way of doing that is to diversify supply chain partners across national borders through providing assistance for information sharing and business matching, as already mentioned.

Third, it is essential to develop international rules so that private companies can appropriately deal with economic regulations concerning national security. There are growing risks that due to national security concerns, exports of specific products to China may be prohibited and that because of a conflict, China may face sanctions, restrict exports, or demand that foreign companies provide technology. To minimize and make those risks visible, it is necessary to develop transparent international rules that stipulate under which conditions specific products or industries may be subjected to investment or trade restrictions for national security reasons. Now that the World Trade Organization (WTO) has ceased to function adequately, it is desirable to discuss and develop such rules under international frameworks, such as the G7, IPEF, QUAD, RCEP, APEC and CPTPP. If Japan develops transparent rules for the designation of “critical products” under the recently enacted economic security law, the Japanese rules could serve as the basis for international rules. I look forward to the Japanese government playing an important role in developing international rules in various cases. I also hope that Japanese companies will actively engage in public communication and dialogue so that the government can understand their positions.

Finally, in the medium to long term, promoting innovation is the key to making Japanese industries more internationally competitive and more resilient, and it is therefore important to expand international knowledge networks. In fact, the policy packages adopted in recent years in Japan, the United States and Europe have included measures to support research and development and international research collaboration in the high-tech sector, including the semiconductor industry. In addition to attracting TSMC's semiconductor production plants to Japan, the R&D center for developing 3D integrated circuits will come to Japan so that Japanese companies and research institutions can undertake collaborative research. In addition, Japan and the United States have agreed to engage in research collaboration to produce a next-generation semiconductor. The Japanese government and companies should take further steps in this desirable direction and make stronger commitments toward engaging in international research collaboration. However, it is necessary to cooperate with countries that do not pose national security concerns in internationalizing knowledge networks, as in the case of internationalization of supply chains—that is, knowledge friend-shoring is essential. Therefore, it is desirable to support initiatives intended to find research partners, such as information sharing, business matching and personnel exchange, through international frameworks among friendly countries (e.g., IPEF and QUAD).