When people form expectations and make decisions, they are subject to constraints, such as limited information-gathering capacity, time, and the ability to think. Such cognitive capacity and available time are called cognitive resources. People try to use these finite cognitive resources in the most rational manner, and in this sense, people are resource rational.

In recent years, studies focusing on the finite nature of people's cognitive resources have been spreading in the fields of cognitive science, psychology, neuroscience, AI research and other research fields. These are also collectively referred to as the analysis of resource rationality. Here, I would like to introduce several resource rationality approaches in economics and consider the implications for research on currency bubbles (deflationary equilibrium) and other themes.

◆◆◆

In macroeconomics, the finite nature of cognitive resources was first emphasized in the theory of “rational inattention” advocated by Prof. Christopher Sims of Princeton University. He pointed out that people restrict their focus in order to effectively utilize their finite attention, which causes a gap between the people’s inference and complete rationality.

Prof. Michael Woodford of Columbia University also states in his paper in 2012 that people, intending to optimize their finite cognitive resources, respond to any gaps between their subjective expectations (reference points) and actual outcomes.

As a result, dependence on reference points arises in people's behavior. Dependence on reference points refers to situations where, for example, if an empty cup is a reference point, then a half cup of water is recognized as 'a lot', but the same half cup of water is recognized as 'a little' when a full cup of water is a reference point.

Dependence on reference points in economic behavior is also well known in the “prospect theory” in behavioral economics. Prof. Woodford said that the emergence of dependence on reference points can be explained by resource rationality.

Additionally, in a 2022 paper, Prof. Xavier Gabaix and Prof. David Laibson of Harvard University discussed how time discounting―evaluating future value as less than that current value―can be explained based on incomplete information and the finite nature of cognitive capacity. Even individuals who do not inherently have a tendency to discount future value eventually behave as if they are, due to increasing noise in predicting a more distant future.¬

Advancement of AI also influences economics. Mr. Artem Kuriksha, a graduate school student at the University of Pennsylvania, in his paper in 2021, proposed a model where people have a multi-layered neural network and conduct deep learning from experienced data. This model assumes that people's expectations are formed similarly to recent AI principles.

Since expectations are formed through learning from experience, differences in experience create differences in expectations. As a result, some save money excessively while others do not save at all, which increases inequality.

◆◆◆

The research presented above highlights that people's expectations are not “perfectly rational.”

Modern macroeconomics is based on the rational expectations theory. Complete rationality, one of the components of this theory, is the assumption that people can make decisions by utilizing all information completely and rationally, which implicitly suggests that people's cognitive resources are infinite. Questioning these assumptions and trying to bring them closer to reality is what the resource rationality approach, that emphasizes the finite nature of cognitive resources, aims to achieve.

The rational expectations theory involves not only the complete rationality idea, but also recursiveness, as its components.

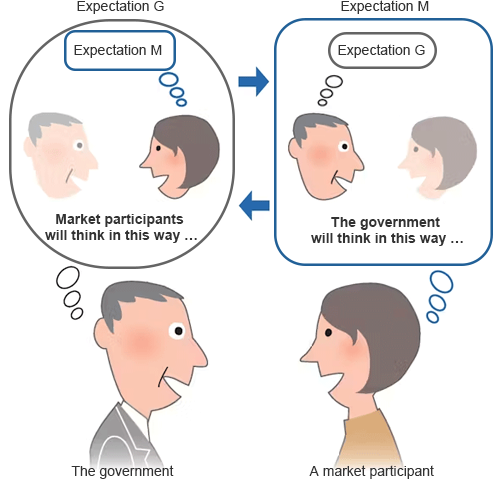

Let us consider the recursiveness of expectations by citing an example of Government G and Market Participant M. This is the example used in my article on February 20, 2017. G formulates policy based on predictions of how M will think and react. Here, the expectation of G (Expectation G) is "G's expectations regarding 'M’s expectations'."

Conversely, M reacts to a policy while considering how her behavior affects G's policy. Here, the expectation of M (Expectation M) is "M's expectation regarding 'Expectation G'."

In other words, Expectation M is determined by Expectation G and Expectation G is determined by Expectation M. The definition of Expectation G includes Expectation G via Expectation M. The characteristic in which something is recurrently a participant in its own definition is called recursiveness.

The recursiveness of expectations is considered to be key in the development of resource rationality approaches.

The possibility that incomplete information and the inherent recursiveness of the relationship change the nature of the equilibrium has been pointed out in theories of global games and higher-order beliefs. It is also known that when the recursiveness of expectations is associated with constraints in cognitive resources, monetary bubbles wherein worthless strips of paper circulate as a currency can occur even in an economy with finite numbers of transactions (as discussed in the 2024 paper by Dr. Janet Hua Jiang, principal researcher, the Bank of Canada, et al.). This is surprising when considering a state of complete information.

In an economy where with a finite number of transactions, the last person to receive money has no opportunity to transact. Accordingly, no one receives money in the last transaction. Knowing this means that no one will receive money in the second-to-last transaction, because there is no one to whom money can be passed in the last transaction.

If there is no one who receives money in the penultimate transaction, there is also no one who receives money in the third-to-last transaction. The continuation of this reasoning results in a situation where no one receives money from the very initial potential transaction, and a currency will cease to circulate.

However, Dr. Jiang, et al. demonstrated that when participants have incomplete information regarding their transactional position in a finite number of transactions, people accept money. This is because in all transactions, people consider that they will have a chance to use the money in the next transaction, and this reasoning also applies in the last transaction.

For example, in the world consisting of only two people, A and B, B considers that A is wondering whether this is the last transaction. In the same manner, A also considers that B is wondering whether this is the last transaction. Furthermore, A and B both recognize that the counterparty is reading their own thoughts, so recursiveness is also observed here.

Incomplete information propagates due to the recursiveness of expectations, meaning that worthless strips of paper circulate as currency even in an economy with a finite number of transactions.

By applying this mechanism of currency bubbles, it may be possible to explain why Japan continues to experience deflation despite the government’s continued increases in the money supply through monetary easing in the 2000s.

Deflation occurs when the value of money increases relative to goods and services. While increasing the money supply should naturally decrease the value of money, the increase in the value of the currency in reality suggests the occurrence of a currency bubble.

Approaches based on the idea of resource rationality, by focusing on recursiveness, have great potential in creating new developments in rational expectations theory.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

October 8, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun