Monetary policy, fiscal policy, and growth strategy management should occur in tandem with the aim of achieving economic stability and growth. Monetary and fiscal policies are short-term demand-side tools used to reduce supply-demand gaps by adjusting demand and achieve economic stability in a state of full employment. Meanwhile, growth strategy is a long-term supply-side tool used to achieve economic growth through the expansion of supply capacity.

However, as different organizations are responsible for monetary policy, fiscal policy and growth strategy, with each organization striving toward its goals within its own jurisdiction, “coordination failures” may occur meaning that the results achieved may create lose-lose situations as a result of the various organizations individually pursuing partial optimization.

A vicious circle theory is often mentioned in reference to the relationship between monetary and fiscal policies. According to this theory, a prolonged state of low interest rates promotes the expansion of government debt, a situation that hampers structural reforms, thereby causing economic growth to remain stagnant, and as a result, it becomes difficult to remove the low interest rate policy.

There is a consensus on the point that both a low interest rate policy and an expansionary fiscal policy relying on increased government debt have the effect of contributing to economic stability by reducing supply-demand gaps. However, there are various opinions on how those policies affect long-term economic growth. Proponents of neoclassical economics argue that whereas neither monetary policy nor fiscal policy affect long-term economic growth, supply-side structural reforms, such as deregulation, have an impact on economic growth.

However, when considering the political effects that policies can have beyond private sector entities, different conclusions arise. If low interest rates continue for a long period, politicians and policymakers assume that interest rate cost associated with government bond issuance has declined, weakening fiscal discipline, leading to increased borrowing and fiscal expenditures. If the government’s fiscal position deteriorates, it is theoretically possible that economic growth may slow due to the deepening of anxiety among households and companies over future prospects (see the research paper co-written by this author and Professor Kozo Ueda of Waseda University in 2022, for example).

In this case, the “anxiety over future prospects” refers to concerns shared by many people over the future sustainability of social security and public services. As such concerns spread, they create a vicious circle of low interest rates causing fiscal deterioration, which causes low growth, which makes it necessary to keep interest rates low.

As this vicious circle represents a coordination failure arising as a result of both the Bank of Japan (BOJ) and the government acting in ways that achieve local optimization within their own area of responsibility, assigning blame is unconstructive. The BOJ and the government should hold discussions from the perspective of overall optimization while considering their own policies’ political effects on the policymakers who are responsible for other policy areas, and to the possibility that fiscal deterioration could have negative effects on economic growth. That is, when the BOJ and the government act locally, within their respective areas of responsibility, they should keep overall optimization in mind.

◆◆◆

Around 2013, when the Abenomics policy was launched, the government’s growth strategy was intended to create an environment that was favorable for the growth of private-sector companies through deregulation and other structural reforms. At present, industrial polices involving significant increases in fiscal expenditure have been brought to the forefront. A typical example is the expansion of the government’s fiscal support for the semiconductor industry.

The government’s fiscal support for the semiconductor industry as a proportion of Japan’s GDP is 0.71% (a total of around 3.9 trillion yen over the past three years), which is smaller than the amount deployed in the United States for their semiconductor industry, but fairly large among major developed countries. With more than 6 trillion yen also provided for gasoline subsidies, fiscal expenditures for industrial policy measures are increasing rapidly in Japan.

It cannot be denied that those industrial policies are intended not only to make the supply structure more efficient but also to stimulate demand in the short term. Another major factor behind the increased fiscal expenditures is the loss of aversion to further fiscal spending due to the continuation of the low interest rate policy over more than 20 years; that is, low interest rates have induced fiscal deterioration, as described earlier.

There is strong justification for industrial policies involving fiscal expenditures when they create global public goods or in cases of coordination failure that cannot be resolved by private agents alone.

One typical example of a public good is research and development on new technologies that are useful for dealing with societal changes such as climate change and aging populations. The government aims to both deliver on its international commitment to reduce of greenhouse gas emissions and achieve economic growth through green transformation (GX) investments by the public and private sectors totaling around 150 trillion yen over the next 10 years. Of the total investment amount, around 20 trillion yen will come from fiscal expenditure financed by the issuance of a new type of government bond known as the GX Economy Transition Bond. It is crucial that GX investments both boost demand in the short term and create new markets and realize supply-side reforms in the long term. Continuous evaluation of policy is essential in this effort, and especially critical is developing a system to prevent moral hazards.

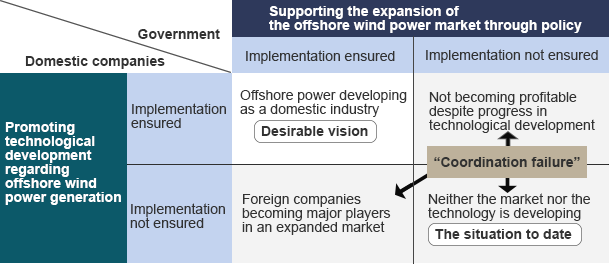

As an example of problems that cannot be resolved by private-sector agents alone, let us examine floating offshore wind power generation. While the potential energy capacity of the wind power available in the seas surrounding Japan is theoretically sufficient to cover primary energy needs in Japan, floating offshore wind power will be the mainstay form of wind power available because of the depth of the seas. The difficult technological challenges involved in floating offshore wind power generation have caused Japanese heavy machinery manufacturers to withdraw from this sector, while Chinese and European companies have held technological superiority with respect to wind turbines and other elements of wind power generation.

One factor that has prevented Japanese companies from overcoming the technological challenges is a lack of sufficient research and development investment. Behind the lack of investment is the Japanese companies’ determination that the risks involved are too high given the uncertainty over the future development of offshore wind power generation in Japan.

In short, private-sector agents cannot take risks because the government has not presented a strong vision for developing the offshore wind power market. On the other hand, the government cannot bet the entire future of Japan’s renewable energy policy on the offshore wind power sector because Japanese companies lack relevant technological expertise. This situation represents a coordination failure between the government and private-sector companies, with each side unwilling to take risks exactly because the other side remains risk-shy.

If the technological challenges were overcome, wind power and related industries would have the potential to grow into a major industrial sector that supports regional employment. The government must resolve the coordination failure by exercising strong leadership in providing reassurances about the future prospect of wind power and encouraging Japanese companies to invest in the technological challenges.

◆◆◆

Increasing fiscal expenditures for the purpose of producing public goods or resolving coordination failures may be a legitimate policy option. However, without satisfactory explanations regarding the financial sources of those expenditures, doubt in terms of policy continuity are likely to increase among the public, then leading to restriction of private sector activity. This is a “fiscal deterioration to low growth” cycle mechanism in which cumulative increases in government debt damage the credibility of policy, hampering economic growth.

In short, going forward, the hurdle to clear is reconciling two contradictory needs—(i) increasing the fiscal expenditure which is essential for GX and measures to raise the birthrate and (ii) preventing the uncertainty over the financial sources from deepening. To that end, it is necessary to develop mechanisms to provide the public with long-term, credible outlooks on policy programs, including funding sources.

What is needed is a neutral organization that does not hesitate to make necessary investments but that also avoids overly optimistic assumptions, such as the idea that economic growth will sweep away debts. One example is an independent fiscal institution (IFI), which major countries have established or are currently planning to establish. We can probably take the first step toward resolving coordination failures when an institution like an IFI has developed and announced long-term forecasts, including prospects for policy exits and future funding sources, to be shared by the policymaking authorities and the public so that long-term trust in policies can be cultivated.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

June 12, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun