The Bank of Japan (BOJ) has started a review of the last 25 years of its own monetary policy from a broad perspective. In December 2023, the BOJ held the first workshop to examine the benefits and negative side effects of its unconventional monetary policy. This article looks back at the unconventional monetary policy from two viewpoints: the natural rate of interest and inflation expectations.

One reason why the unconventional monetary policy became necessary was a decline in the natural rate of interest (the interest rate at which supply and demand match on an economy-wide basis). If the natural rate of interest becomes negative and low inflation continues it is difficult to align real interest rates with that rate, because even if nominal interest rates have been reduced to zero, real interest rates remain high. The unconventional monetary policy (e.g., quantitative easing and forward guidance, which refers to a commitment to future monetary easing) was introduced for that purpose. It was expected to directly raise the people’s inflation expectations.

According to some estimates, the natural rate of interest has been trending downward in Japan since the second half of the 1990s. Paul Krugman, the economist who first argued for the adoption of an unconventional monetary policy in 1998, also pointed out that the natural rate of interest in Japan had become negative.

There are various factors that could account for the decline in the natural rate of interest, including the aging of society and low birthrate. Summarizing all those factors, Krugman argued that the natural rate of interest in Japan was declining because of the long-term expectation that the Japanese economy would contract in the future. He went on to assert that one effective way of resolving the demand shortage seen at that time was to boost the demand by adopting an unconventional monetary policy, taking the decline of Japan in the long-term as a given condition.

◆◆◆

However, if the decline in the natural rate of interest is the problem, adopting a policy that aims to raise that rate (raise the economic growth rate over the long term) should be the right course of action in principle. The natural rate of interest cannot be increased through monetary policy measures. This is because in order to increase productivity, implementing structural reforms in the labor and financial markets is essential. That is exactly what a growth strategy is.

Indeed, a joint statement issued by the government and the BOJ on January 22, 2013, stated that the government would “formulate measures for strengthening the competitiveness and growth potential of Japan's economy and vigorously promote them” together with the BOJ’s monetary easing. However, whether or not those measures were effectively conducted is unclear. Verifying the progress made in the implementation of the governmental measures and improving their effectiveness is a major challenge going forward.

Although expansionary fiscal policy accompanied by increased fiscal expenditure may have temporary economic-stimulating effects, it is unable to raise the economic growth rate or the natural rate of interest in the long term. On the contrary, such policy could increase concerns over the future of fiscal management, leading to declines in the economic growth rate and the natural rate of interest, as pointed out by my 2022 paper with Professor Kozo Ueda of Waseda University. In other words, it is necessary to implement structural measures intended to promote growth simultaneously with “measures aimed at establishing a sustainable fiscal structure,” which were mentioned in the BOJ-government joint statement.

The next question is whether unconventional monetary policy can create inflation expectations. Underlying the argument for the unconventional monetary policy—that increasing money supply under the zero-interest rate environment will lead to inflation—was the reasoning that if prices do not increase in the future despite an increase in money supply, transversality conditions concerning future currency value would no longer be satisfied.

In simpler terms, the reasoning can be described as follows. If prices do not increase despite an increase in money supply, some amount of currency in circulation may be left unused and remain as a surplus. However, if currency-holders are rational, there should be no such surplus. Therefore, prices should increase so that no surplus money remains unused.

While this argument may initially seem very solid, it is predicated on the central bank’s ability to manipulate people’s long-term expectations that money supply will continue to increase until the distant future. In other words, the assumption is that the central bank can, through its current policy, control ordinary people’s long-term expectations concerning the distant future, but is that assumption valid?

There are two problems that make it theoretically difficult to create inflation expectations. One is the absence of a device that guarantees that commitments by the central bank will be implemented, and the other is the time inconsistency problem. For example, even if the BOJ has increased money supply and declared an intention never to reduce money supply until inflation firmly takes hold, it would not impact people’s lives or the business environment for companies because interest rates in Japan have remained near zero for many years. In effect, the BOJ would be doing nothing more than announcing a plan that may or may not actually be carried out.

If ordinary people believe that the BOJ could reduce the money supply if inflation rises, a BOJ announcement of its future plans is unlikely to counteract that belief. Apart from interest rates with which they are familiar, there is no other basis for the people to believe that a BOJ commitment regarding a distant future (e.g., future levels of prices and money supply) will be honored.

As for the time inconsistency problem, in order to create inflation expectations in times of deflation, it is necessary to convince the people that the BOJ will maintain monetary easing for a sufficient period after the onset of inflation. However, once inflation has begun, common sense dictates that the BOJ will lean toward monetary tightening as early as possible as it wants to avoid excessive inflation.

In other words, the optimal action for the BOJ in times of deflation is to make a commitment to maintaining monetary easing in the long term even if inflation occurs in the future. Even so, once inflation has emerged, the BOJ has a strong incentive to ignore that commitment and quickly shift to monetary tightening. For the BOJ, honoring the ex-ante optimal commitment may not necessarily turn out to be optimal ex-post. In this case, time inconsistency refers to the difference between what is optimal at the time of the commitment and what later turns out to be optimal.

When such a time inconsistency problem exists, a commitment to maintaining monetary easing after the onset of inflation is highly likely to be ignored. The people, likewise, expect that the commitment will be ignored, resulting in the loss of credibility of commitments by the central bank. The fact that the central banks in the United States and Europe, which had long promised to maintain monetary easing, suddenly shifted to rapid, steep interest rate hikes since 2022 in response to rising inflation, appears to be a typical example of the time inconsistency problem occurring in the real world in the eyes of monetary policy amateurs. This experience may have further weakened the credibility of central banks’ commitments.

◆◆◆

Given the double burden of the absence of a device to guarantee central bank commitments and the time inconsistency problem, the monetary authority’s commitment to maintaining monetary easing after the onset of inflation is unlikely to be trusted. The idea that policymakers can control ordinary people’s expectations regarding the distant future, thereby leading to inflation, is implausible as an economic theory.

[Click to enlarge]

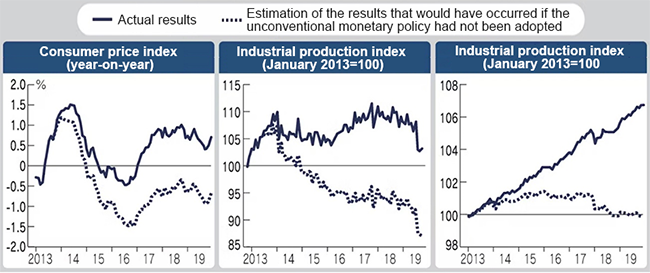

Of course, the monetary authority’s announcement of a strong resolve regarding future action could have a “psychological effect” that could influence people’s expectations, and many empirical studies have shown that the BOJ’s unconventional monetary policy has actually had the effect of boosting the economy and prices. The figure above shows the analysis results based on the BOJ’s broad policy review, claiming that as a result of the unconventional monetary policy, which was introduced in 2013, prices, production volume, and jobs all increased. However, as mentioned earlier in this article, it is still theoretically difficult to fully guarantee that the unconventional monetary policy can reliably generate inflation expectations.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

February 14, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun