Global warming, the demographic crisis (the aging society, the low birthrate, and the shrinking population), fiscal sustainability, and the final disposal of radioactive wastes from nuclear power stations are a type of policy challenge from which the current generation of people can gain no benefits even if they pay the costs for resolving them, but which will bring benefits to future generations. In short, they are intergenerational problems.

If existing intergenerational problems are discussed from the viewpoint of a hypothetical future generation—people in a world 50 years from now, for example—different policy decisions may be arrived at compared to when the problems are discussed from the current generation’s viewpoint. In the February 13, 2018 edition of this column, I introduced readers to the future design initiative, being led by researchers and practitioners who are studying this matter and trying to reflect future generations’ interests in policymaking by local governments. At this time, I will discuss what kind of approach may be taken toward intergenerational problems from philosophical and ethical perspectives.

◆◆◆

To achieve the sustainability of the global environment, society, and the economy, it is necessary to establish intergenerational ethics. Intergenerational ethics is a discipline that explores the question of whether the current generation can pay the cost of resolving intergenerational problems when they cannot expect to benefit from those costs. Toshiaki Hiromitsu of the Policy Research Institute under the Ministry of Finance dealt with this matter squarely in his book.

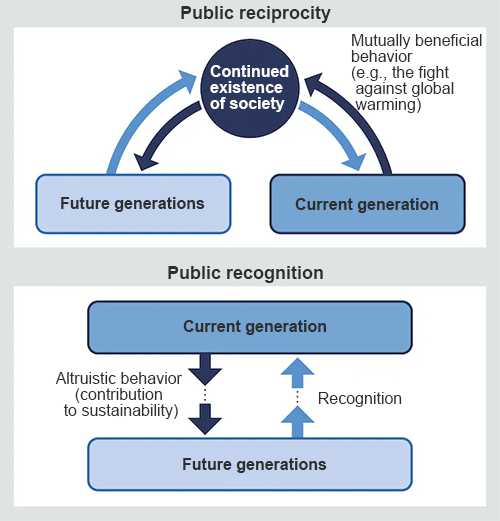

Citing an argument by Professor Samuel Scheffler of New York University, Hiromitsu asserted that there is a relationship of mutual public benefit between current and future generations as follows. People would feel that most of what they achieved in their lives would be meaningless if they knew that society would come to an end soon after their death. In other words, Scheffler argues, the continued existence of society is our greatest concern. The continued existence of society is a value that can be shared by both current and future generations. Protecting that value is an act that is mutually beneficial for both current and future generations (Hiromitsu calls this “public reciprocity”). If the current generation pays the cost of protecting that value, they may appear to be making an unrewarding self-sacrifice, but in fact, they do so in anticipation of contributions from future generations (see the upper panel of the figure below).

The altruistic behavior between generations is said to be possible because of a sense of connection with the humans of future generations, allowing current people to treat the interest of the future generations as their own. Here, I would like to propose the concept of “public recognition” as an idea that is mutually complementary with the relationship of public reciprocity outlined above.

According to the Hegelian philosophy as interpreted by Professor Axel Honneth of Columbia University, human history is the struggle for recognition. Both individual persons and nations struggle for recognition from others in order to satisfy their own desire for recognition. Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” theory, which was based on a similar historical perspective, maintained that liberal democracy is the ultimate form of government because it is a political system that maximizes mutual recognition between the people.

However, it is not that recognition from others in itself has a fundamental value. Rather, the persons who give me the recognition that I value also themselves need to gain recognition from others. If we trace this chain of recognition through time, ultimately, we arrive at recognition from yet-to-be-born generations in an infinite future. Scheffler’s argument—that we are unable to find meaning in our life unless we believe that society will continue to exist after our death—can be understood to mean that individuals’ purpose in life has meaning only if we can expect to gain recognition, directly or indirectly, from future generations.

The concept of public recognition holds that the basis of the value of what we pursue, including for selfish reasons, is recognition from yet-to-be born generations in an infinite future. Individuals who have an awareness of public recognition are more strongly tempted to behave altruistically for the sake of future generations when their desire to serve their own interests is stronger. That is because people who seek recognition for selfish reasons have a strong desire to gain recognition from future generations (see the lower panel of the figure above).

It is natural for us to have a sense of connection with future generations who satisfy our desire for recognition. This natural connection for future generations forms the basis of the relationship of public reciprocity. Moreover, the connection with future generations further increases the value of recognition gained from them for our generation. Public reciprocity and public recognition mutually complement each other.

In order to invigorate public reciprocity and public recognition, it is desirable that the current generation’s preferences change. The deliberative democracy initiative can be considered to be an effort to make that happen.

With respect to the argument that citizen deliberation—deliberation at civic gatherings and mini-publics events, for example—changes the people’s mindset, there has been a controversy between proponents who emphasize the impact that citizen deliberation has had on important policy decisions regarding matters such as climate change (e.g., Professor James Fishkin of Stanford University and Professor Hélène Landemore of Yale University), and skeptics who, while acknowledging the significance of citizen deliberation, assert that its role should be nothing more than supplementary (e.g., Professor Ian Shapiro of Yale University and Professor Cristina Lafont of Northwestern University).

In the arguments over deliberative democracy, deliberation among the current generation is the main focus. The arguments lack the perspective of future design, which looks at things from the perspective(s) of future generations. However, going forward, deliberative democracy coupled with future design will help to complement democratic decision-making so that it can deal with inter-generational problems.

There are also several initiatives aimed at influencing the current generation’s preferences by creating some kind of institutional system or organization. One of them aims to provide a legislative basis for the formulation of intergenerational sustainable development plans. In Wales, the Well-being of Future Generations Act is a pioneering example of this. According to a recent book by Project Professor Tsuyoshi Saijo of Kyoto University of Advanced Science, this law, enacted in 2015, provides guidelines for the Welsh government’s formulation of development plans in order to increase the appeal of the region’s natural environment, culture, and heritage.

Another example is the establishment of independent fiscal institutions, which are becoming more and more common in Europe and the United States. Independent fiscal institutions are neutral entities that present long-term fiscal projections for the next four or five decades to the people and governments. Establishing such an agency is expected to increase information about the future that is available to the people and help to incorporate consideration for future generations into the current generation’s policy decision process.

◆◆◆

To conclude this article, let me introduce a utopian vision. An ideal institutional system is one that brings about the kind of outcome depicted by The Fable of the Bees, written by Bernard de Mandeville, that is, where the people’s actions based on the selfish motives unintentionally strengthen the sustainability of society.

One example of an institution that could produce such an outcome may be an electronic money system based on carbon emission credits. A currency system based on the gold standard could cause a gold rush among greedy, selfish people. However, if emission credits can be used as currency, people are expected to try to create credits due to the profit motive. They will voluntarily engage in forestation activity and develop technology to reduce carbon emissions.

Pursuing profit, which is a selfish motive, would lead to public good activity through the activities that are necessary to create emission credits. Emission credits would circulate as currency in a situation similar to the popularization of crypto asset mining which advanced despite the absence of government regulation. If the people believe that yet-to-be-born generations in an infinite future will recognize the value of emission credits as currency despite the absence of a strong regulatory measure, such as the imposition of governmental restrictions on emission volumes, the emission credits (that is, the currency) would become a shared value. This means that an emission credit-turned-currency would in essence become a present embodiment of the public recognition.

Intergenerational problems are difficult for any existing political system to resolve. It is imperative to create a new political philosophy and decision-making mechanism that complement our democratic systems.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

June 16, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun