What should be the design of social systems in order to solve intergenerational policy issues affecting the sustainability of our society—such as global environmental problems, a declining population, and swelling government debt—and ensure that we pass on a sustainable natural environment and human societies to our future generations? A research movement called "future design" is about finding the answers to this question.

The movement advocated by Tatsuyoshi Saijo, founding director of the Kochi University of Technology Research Institute for Future Design, was initiated in 2012 by a group of researchers, mainly from Osaka University. It has expanded across disciplinary boundaries to involve researchers from various fields including economics, psychology, ethics, and neuroscience today. On January 27-28, 2018, the First Future Design Workshop was held at the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature.

♦ ♦ ♦

One of the purposes of future design research is to bring on actors representing the interests of future generations to take part in present-day political decision making. An experiment introduced in a 2017 paper co-authored by Osaka University Associate Professor Keishiro Hara and Professor Saijo typically reflects this idea.

The experiment, conducted in 2015 in the town of Yahaba, Iwate prefecture, asked citizens to draw up a long-term vision, which would define the future course of the town over the period through 2060, with the help of a group of researchers studying future design. The participants were split into four groups—each consisting of five to six members—to discuss and develop a draft plan. Two of the groups were to represent the interests of the current generation, whereas the remaining two groups were asked to stand in the shoes of future generations who would be active in 2060.

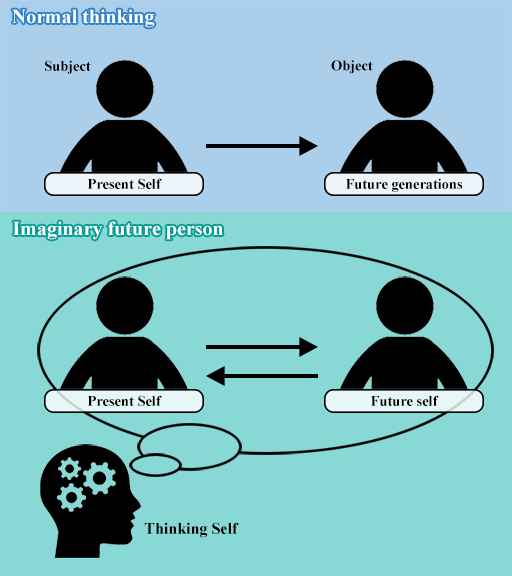

As it turned out, there was a distinct difference between the first two and latter two groups in their way of thinking and agreement reached. For instance, whereas the current generation groups drew up a vision as an extension of the status quo, taking the constraints and challenges that exist today as given, the future generation groups called for efforts to address tough challenges in order to enhance the strengths of the town. When they were interviewed half a year later, those in the future generation groups said that they had been able to take an objective view of themselves and reconcile conflicting interests between their two selves, i.e., the present self and the future self, and that they were glad to have been able to think that way.

Professor Saijo calls this future self a "Imaginary future person" (Figure). If those of us who belong to the current generation think in the shoes of a Imaginary future person, we would be able to make our society more sustainable. Some researchers are considering the possibility of establishing a government agency representing the interests of future generations—e.g., "Ministry of the Future" as part of the central government and "Department of the Future" as a unit within a local government—as a specific measure to reform relevant institutional systems.

♦ ♦ ♦

At the workshop, a series of social experiments with deliberation among citizens conducted in various part of Japan—including the one conducted in Yahaba, Iwate prefecture; as well as those in Matsumoto, Nagano prefecture; Kochi prefecture; and Onuma in Hokkaido—were presented. In all of the experiments, the presence of a participant assigned to represent the interests of future generations made a difference to the outcome of deliberation.

Interestingly, researchers had the impression that there were significant changes in the psychology and emotions of those participants assigned to represent future generations. This suggests that some changes have occurred in the brain activity of those participants. In the light of this observation, some researchers proposed a research project, in which functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) would be used to measure changes in the brain activity of participants in the course of deliberation.

In addition, a group led by University of Tokyo Professor Tatsuya Kameda presented the results of a psychological experiment, pointing to the tendency that those with offspring are more concerned about the interests of future generations than those without. Meanwhile, Waseda University Professor Tomohide Suzuki introduced India's "One Additional Line" financial reporting scheme as a real-world example of successful institutional design. The scheme made it mandatory for listed companies to report the amount spent on corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities in the income statement. Concerned about their reputation, Indian listed companies have increased their CSR spending significantly, to the tune of 300 billion yen a year.

Kochi University of Technology Professor Yoichi Hizen presented the results of an experiment that tested how people react to the introduction of Demeny voting, which would give minors the right to vote and let their parents or guardians vote on their behalf. The experiment found that those without children voted more in favor of the current generation under a Demeny voting system than under the conventional voting system. This suggests the possibility that the emergence of those representing the interests of future generations could provoke a backlash from other people. This is an interesting finding and should be kept in mind in considering a new system design.

As possible directions for future design research, I would like to raise three questions to ponder.

♦ ♦ ♦

The first question is how an imaginary future generation (represented by public agencies such as the Ministry of the Future) would function. Suppose that we create agencies representing the interests of future generations. But then, how and why can we be sure that these agencies will truly represent the interests of future generations and keep an eye on the public policy process of the current generation?

If the above experimental finding that participants assigned to represent the interests of future generations were able to act as imaginary persons holds true in general terms, public agencies such as the Ministry of the Future could work properly. Assigned to represent future generations, officials of the Ministry of the Future would take on the personality of imaginary future persons. In order to evaluate this point scientifically, it is necessary to explain scientifically the mechanism by which imaginary future persons form their identity by applying statistical techniques typically used in brain science and psychology.

The second question is where to find the politico-philosophical grounds for justifying the creation of an imaginary future generation (i.e., establishment of a new institutional system such as the Ministry of the Future). In order to establish a new institutional system for future generations, such reform must have legitimacy in the current political system of democracy.

For instance, many scholars in law and political science remain opposed to Demeny voting, which they see as violating the fundamental principle of democracy called “one person, one vote.” Simply being necessary for future generations does not necessarily warrant public acceptance. In order to gain broad public support, we need to develop a political philosophy that justifies the creation of an imaginary future generation in the current landscape of democracy.

We might be able to justify it by drawing on a social contract theory (“A Theory of Justice”) advocated by John Rawls, an American philosopher, using the “veil of ignorance.” If people are to agree to a social contract without knowing which generation they will be born into (i.e., they are covered by the veil of ignorance), they would be afraid of being born into the most unfortunate generation and therefore should support the creation of an imaginary future generation so as to reduce the burden on such generation.

The third question is what it would take for ordinary people to spontaneously become Imaginary future persons. In other words, what does it take to make people more altruistic (loving) toward future generations? This may be better defined as a political thought question, going beyond the realm of science.

Although it may seem paradoxical, when we think about love for future generations, connecting with the past is a critical factor. Disconnecting our current society from its past would make us feel rootless, which would undermine our motivation to fulfill our responsibility as the current generation and pass our society onto future generations. The sense of weariness resulting from the severance from the past would gradually paralyze society. This is what we might call the "revenge of the past," which makes us delay efforts to tackle fiscal and environment problems.

Only when people feel that their present is connected with the past can they embrace love for future generations and feel willing to take on whatever it takes to pass this world on to the next generation. Just like love for individuals, love for the world is a faith given by history, not by reason. Maybe we should say that our challenge is to restore our history from the past into the future and rediscover the public things that should be passed down throughout history.

Future design research may change the nature of human knowledge in a broad spectrum of fields including not only social science but also neuroscience and political philosophy. It is hoped that various studies will be carried out under this new framework.

* Translated by RIETI.

February 13, 2018 Nihon Keizai Shimbun