PDF version [PDF:233KB]

How to Look at the Rate of Return on Higher Education

As the Fourth Industrial Revolution, encompassing Artificial Intelligence (AI), Big Data and the Internet of Things (IoT) has progressed, with new knowledge and ideas becoming great sources of economic growth, education has become an investment in the next generation who will be responsible for the future. Education is also a "long-term national plan," the key to breaking the cycle of poverty in overcoming the different conditions that children are placed in. In other words, education, which plays a role in the formulation of "human capital," is not only a source of growth but also possesses the function of correcting disparities.

Under such circumstances, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe introduced the promotion of a "Revolution in Human Resources Development" at a press conference on June 19, 2017. Free higher education and university reforms are its pillars, and the prime minister appointed the former chairman of the Policy Research Council of the Liberal Democratic Party, Toshimitsu Motegi, to concurrently serve as minister for this "Revolution in Human Resources Development" and as minister of state for economic and fiscal policy. It goes without saying that education is a "long-term national plan" which must not be used as a policy just to "attract popularity." To begin with, what is the impact of higher education in looking at its relationship with human capital investment and growth? Empirical analysis of the impact of education is not easy, but from a cost-benefit analysis perspective the rate of return on education serves as an important indicator of the impact of the educational budget.

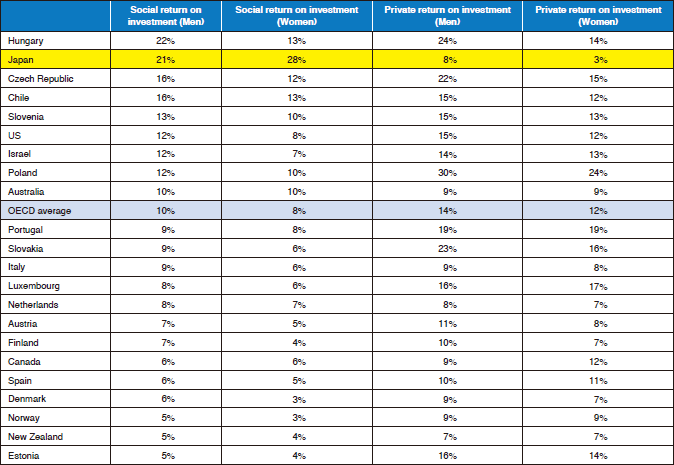

The rate of return on education implies a "rate of return where education is considered to be an investment in human capital," and there are two concepts that exist: "private rate of return" and "social rate of return." Of the two, private rate of return refers to "internal rate of return calculated from private expenses which includes private benefits such as additional lifetime earnings obtained through university education, and acquired earnings lost (opportunity costs) with university admission and admission costs." Social rate of return refers to "internal rate of return calculated from the sum of benefits which includes social benefits such as increased tax incomes through education and lower employment rate, and the sum of expenses which includes social expenses such as financial subsidies and scholarships, etc."

For example, according to the "Useful Labour Statistics 2015—Series of Processed Indices of Labour Statistics" published by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, while the average lifetime wages that high school graduate workers (men) receive are around 240 million yen, the lifetime wages for those who finished university and graduate schools are around 311 million yen, and the difference in lifetime wages between high school graduate workers and university graduate workers stands at around 70 million yen.

On the other hand, "Education at a Glance 2016," an OECD reference material on education, shows that private rate of return (annual) on higher education in Japan was at 8% for men and 3% for women, lower than the OECD average (14% for men and 12% for women). This reflects the situation in Japan where the wage disparity between university graduates and high school graduates is not as large compared to other OECD countries. But given the low standard of public payment on higher education in Japan, the social rate of return (annual) is much higher than the OECD average (10% for men and 8% for women) at 21% for men and 28% for women.

How to Acquire the Financial Resources

What about the financial resources? To begin with, there is fundamentally no "free lunch" with policies and there is a need for some type of financial resource. If free higher education, one of the pillars of the reform, was to be implemented, what sort of financial resources will be required? Hints to this can be found in the reference materials for the Eighth Proposal of the Headquarters for the Revitalization of Education (May 18, 2017).

This paper publishes estimation results which show that if tuition for higher education including universities and professional colleges were to be made free, financial resources of roughly 3.7 trillion yen (equivalent to a consumption tax rate hike of 1.4%) would be required, and even if an income restriction (households with income below 9 million yen) was implemented, financial resources of roughly 2.7 trillion yen (consumption tax rate hike of 1%) would still be required.

In addition, if the entire amount of tuition fees were to be exempted for households with less than 3 million yen or if they were half exempted for households with income between 3 million and 5 million yen, financial resources of around 0.7 trillion yen would be required. But under the current grave financial situation, it is not easy to secure such sums every year.

Under such circumstances, an "education bond" concept to secure new financial resources is looming in the political arena, and could possibly ignite a fire. Educational bonds are bonds issued with the purpose of extending financial resources for higher education including universities. It is, in essence, an educational loan where the entire next generation (children) pays off the loan with their own tax payments once they grow up to be adults, and if its social rate of return exceeds the market interest rate, then the "education loan" may be theoretically justified.

[Click to enlarge]

However, under the current financial situation, tax income cannot cover current expenses including the educational budget, and the fiscal deficit is chronic. In other words, issuing deficit bonds has become chronic, and it can be said that a portion of that has become an "education bond." Thus, issuing more bonds in the noble cause of "education" should not be tolerated.

During the House of Representatives Election (October 2017), Abe announced his intention to use roughly 2 trillion yen, a portion of the increased income from the consumption tax rate hike planned for October 2019, in financial resources for child care support and free education. But since free daycare for children and kindergarteners was also announced, there were no prospects of securing financial resources for free education.

As a result, the government and the LDP went on to consider targeting students from households with income of less than 2.6 million yen for free higher education, but this would result in excluding students from households with income of more than 2.6 million yen, and the initial enthusiasm for the reform began to fade.

This cannot be helped since there is an aspect of limitation to financial resources, but it still leaves the fundamental question of why students from households with an income of less than 2.6 million yen are able to apply for free education while students from households with an income of 2.7 million yen cannot. Can the LDP-Komeito coalition continue consultations within the government and seek ways to somehow resolve the challenge of financial resources?

Similar Mechanism to the Australian Mechanism Can Be Replicated with Fiscal Investment & Loan Program

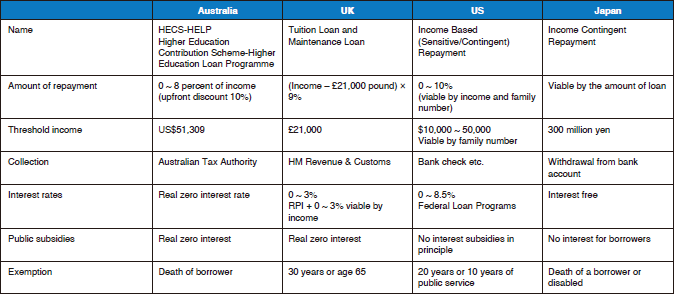

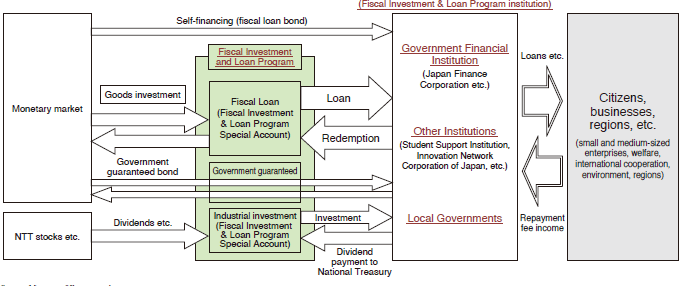

Hence, some experts are focusing on the newly introduced schemes, "Higher Education Contribution Scheme" (HECS) in Australia, and its successor "Higher Education Loan Programme" (HECS-HELP), and the Japanese government has also announced its consideration of a similar system under the "Revolution in Human Resources Development." (For more details on HECS and HELP, see Risa Itoh, "Recent trends in cost bearing system for higher education in Australia," National Diet Library Reference (658) pp. 113-121, 2005.) In fact, the LDP's Headquarters for the Revitalization of Education has also announced that it aims to come up with details of a system by the first half of 2018, where tuition while at university will be exempted and the loan paid back after graduation once graduates start working, referencing the Australian system and others. Laying out the conclusion first, I believe that with adequate political leadership from the government, a system resembling the Australian system may be achieved by using the Fiscal Investment and Loan Program.

[Click to enlarge]

The process will be explained in steps. First, HECS-HELP can be considered a "career advancement" system, and tuition is free while attending university. Upon graduation, the tuition is paid back under the taxation system according to income, and roughly more than 80% of the students receive payments such as HECS-HELP etc. (the numerical data for "roughly more than 80%" is from Hiroshi Suzuki, "Scholarship system in Western nations and the situation in Japan," 2005 (http://www.suzukan.net/03report/syougakukin_ronbun.html). While HECS-HELP is a no-interest framework for selected students, there are other interest-bearing frameworks such as FEE-HELP that other students can apply for.)

To be more concrete, if taxable income after graduation exceeds 5 million yen (Australian $56,000), repayments are made at a return rate of 4% to 8% depending on the amount of taxable income, and once the repayments reach the total amount of the loan, the repayment is complete. To note, the real interest on the repayment is zero, the nominal interest rate is only the inflation rate, and repayments are exempted when the grantee of the loan is deceased. Under HECS-HELP, students are able to choose between receiving a 20% reduction on tuition for higher education in the form of advance payments every semester, or paying back the total amount of the loan through the tax system (e.g. tax withholding) once taxable income exceeds the minimum amount.

This HECS-HELP is a type of "Income Contingent Loan" (ICL), and while not widely known, Japan has also introduced an ICL type scholarship from the Japan Student Services Organization using the overseas mechanisms as references. For example, under the "Income Contingent Loan Type Scholarship System" which the Japan Student Services Organization introduced in April 2017, while there does exist a 2,000 yen minimum monthly repayment, it allows repayment at a rate of 9% interest depending on income, and if annual earnings are lower than 3 million yen, the repayment is deferred in principle. This is more or less the same as the mechanism in Australia, but the difference is in the application conditions for the loan, the benefit rates, the repayment methods, etc. The ICL system of the Japan Student Service Organization differs from the Tax Withholding System of Australia (HECS-HELP) in that repayments are made through direct bank debit and other similar methods. In addition, compared to Australia, scholarship application is limited to those students from households with annual income (legal guardian or total of both parents) of less than 3 million yen, and this is very strict.

For application conditions, "Preliminary Findings of the Follow-up Surveys of High School Graduate Students" conducted by the Center for Research on University Management and Policy of the University of Tokyo (2007) is useful. According to this report, while the percentage of those who went on to study at four-year universities was 62.4% for households with an annual income of more than 10 million yen, the percentage goes down to 49.4% for households with an annual income between 6 and 8 million yen, and for households with an annual income of less than 4 million yen the percentage goes down to 31.4%. The Constitution of Japan states that "As set forth by law, all Japanese citizens are entitled to the right to receive education equally according to their abilities" (Article 26 Paragraph 1), and if children of low-income families wanting to go on to study at four-year universities are indeed unable to receive that education because of the family situation, then that is a problem, and it is vital that equal opportunities are sought so that all citizens can receive higher education.

[Click to enlarge]

The main cause of this problem is the so-called "liquidity constraints" which households face. The aforementioned statistical research says 70 million yen, but generally the difference in lifetime earnings (average) between university graduates and high school graduates is said to be more than 50 million yen, and if one can get into a four-year university one can earn private marginal benefits in the amount of more than 10 times the tuition of four-year universities. Thus, if a student can receive a temporary loan for tuition and living expenses for the four years while at university, there will be ample return and the loan can be repaid with income that will be earned after graduation. But in reality, when households try to get a loan, they have no choice but to face interest rates that are higher than the interest on savings. Since getting a loan is more difficult than savings, there are cases where there is no chance of getting a loan.

This situation where such restrictions on financing exist is called "liquidity constraints," and the policy method to resolve this in the education field is "scholarship." It would be ideal to expand the ICL scholarship system of the Japan Student Service Organization to aggressively address this issue. In this instance, since the Japan Student Service Organization currently already uses the Fiscal Investment and Loan Program mechanism, etc. to obtain funding for scholarships, expansion of the ICL system requires expanding the Fiscal Investment and Loan Program mechanism.

Challenges & Essence of "Career Advancement Type" Scholarship

As there have already been challenges with the ICL (=HECS- HELP) in Australia, ICL may have the potential for losses on unpaid loans if there are too many low-income households, and there is a need to note this point when considering its expansion.

This is because the "government recovery rate is roughly 80%" for the ICL (HECS-HELP) in Australia (as noted by Shiro Armstrong and Bruce Chapman in "Japan's ‘Income Contingent Type’ scholarship system reform is not enough under global standard" (Nihon Keizai Shimbun, ‘Economics Class,’ June 20, 2017). As of June 2013, there has been roughly 700 billion yen (A$710 million) in accumulated losses, and new loan applicants for 2013-2014 were estimated to produce additional losses of around 100 billion yen (A$110 million). In addition, the ICL in the United Kingdom was estimated to hold roughly 3 trillion yen (£16-18 billion) of accumulated losses at the end of fiscal 2012, and there are estimations that calculate accumulated losses in the amount of roughly 16 trillion yen (£70-80 billion) by the end of fiscal 2042.

What Is Required to Solve This Problem?

First is to set the minimum amount related to the ICL moratorium of repayments adequately. Naturally, if the minimum amount of the ICL is lifted, the losses associated with unpaid loans will become larger. But the real question is whether the minimum amount is adequate or not. For example, the ICL in Australia has the minimum amount set around 5 million yen, and since the average annual earnings in Australia are 7 million yen, the minimum amount is 70% of the annual earnings. In Japan, the minimum amount for the ICL is 3 million yen, and since the average annual earnings in Japan are around 4.5 million yen, the minimum amount in Japan is also at around 70%. Thus, the minimum amount in Japan (3 million yen) is at the same level as Australia and therefore it is thought that further reduction is not necessary. On the contrary, to condense losses associated with the unpaid loans, the mechanism that basically allows a grace period for repayment for households with annual earnings of less than 3 million yen should be modified. For example, in addition to the minimum monthly repayment of 2,000 yen, the repayment rate can be revised to [9-0.03 × (300-Z)] % for annual earnings of Z million yen (Z is less than or equal to 3 million yen).

Second, since losses on the ICL are written off in the mid to long term, additional payments (for example, an additional payment around 1% on top of the 9% repayment rate) can be introduced. Once this is set, students who are likely to become mid-to high-income workers can be included as much as possible in the ICL. In other words, losses that will arise with unpaid loans of low-income workers will be written off with additional payments levied on the mid-to high-income workers. But in reality, it is impossible to predict which students will become high-income workers and which ones will become low-income workers. Thus, one of the policy options may have to be having a mechanism for one-time repayment or prepayment, and that all students join the ICL at least once.

However, tuition at private universities is set higher than tuition at national universities, and tuition also varies depending on what the students major in, such as medicine, and thus when introducing additional payments it may give rise to unfairness depending on which university the student chooses and what the student majors in. Two choices can be considered to resolve this.

The first is to set the maximum scholarship amount to be issued by the ICL to correspond to the tuition at a national university. For example, if annual tuition at a national university is 600,000 yen and 1 million yen at a private university, the cap on the scholarship can be set at 600,000 yen and the remainder of the tuition, 400,000 yen, can be paid up front. If such a policy were to be implemented, payment of a certain percentage of the tuition will remain, but tuition for students enrolled at national universities will be zero.

The other is to set additional payment at a "set amount" rather than a "percentage." For example, setting a monthly payment of 3,000 yen. This means that for households with less than 3 million yen in annual income, the minimum monthly payment will be 2,000 yen and for households with annual income of more than 3 million yen, in addition to repayment at 9%, an additional payment of 3,000 yen will be set. In this case, even if tuition differs between universities and departments, the inequality in additional payments that arises from which university or what major one chooses will be eased.

A third choice is to utilize the My Number system and make sure incomes are properly captured and repayments are made appropriately. The ICL utilizing the My Number system has already been implemented for students starting the school year in April 2017, and for taxable household income the Japan Student Service Organization will use the My Number submitted by the students to obtain information on taxable income. The Japanese ICL currently uses direct bank debit, but if the ICL were to be extended, collection must be undertaken strictly, and to strengthen the scholarship collection the Australian (HECS-HELP) method of tax withholding will need to be considered.

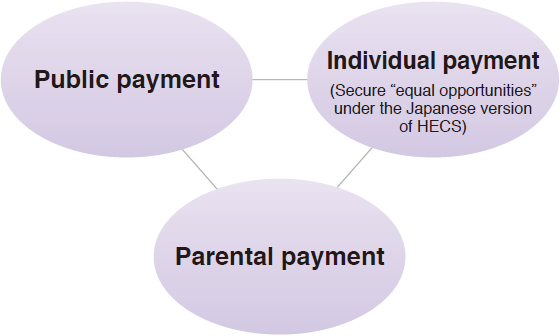

Either way, as Nelson Mandela, who strived to abolish apartheid and became the first African president of South Africa, said, "Education is the strongest weapon. Education can change the world." The Japanese version of HECS and the expansion and extension of the ICL scholarship means that Japan needs to fundamentally transform the way the cost of higher education is covered, and change the system so that what used to be mainly paid by parents will be transformed to be jointly paid by the student and society which benefits from higher education. This shift is also related to the question of where the "center of gravity" of the education burden should be placed. For a country with poor natural resources, human resources are Japan's greatest asset and thus, needless to say, a Revolution in Human Resources Development is important. But it is also highly hoped that a Japanese version of HECS will come to life through adequate political leadership, with considerations to ICL loss write-offs and financial limitations.

This article first appeared on the May/June 2018 issue of Japan SPOTLIGHT published by Japan Economic Foundation. Reproduced with permission.

May/June 2018 Japan SPOTLIGHT