In late 2023, Japan's international rankings for gross domestic product and productivity were published. Japan’s nominal per capita GDP in 2022 released in the revised National Accounts ranked 21st among the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the lowest among the Group of Seven countries. According to the International Comparison of Labor Productivity 2023 by the Japan Productivity Center, Japan’s per capita labor productivity in 2022 ranked 31st among the OECD members.

Additionally, due to the yen’s depreciation, Japan was overtaken in terms of total GDP by Germany with less than 70% of Japan’s population, falling to fourth place in the world. News reports lamenting declines in Japan's economic status seem to have become frequent. However, focusing on the latest rankings alone does not lead to solving the problems facing Japan. In this paper, we would like to discuss Japan's options, including the improvement of labor productivity, while keeping in mind the international status of the Japanese economy.

◆◆◆

Why do international rankings of economic well-being indicators such as per capita GDP and labor productivity differ? While the numerator for both per capita GDP and labor productivity is GDP, the denominators that divide GDP for these indicators are different. GDP is divided by population for per capita GDP and by the number of workers or working hours for labor productivity. What has a greater impact is the difference in the dollar-yen exchange rate when GDP is converted to dollars. Since Japan’s Cabinet Office uses a temporary exchange rate for ranking per capita GDP, the ranking is affected greatly by the recent depreciation of the yen.

On the other hand, the Japan Productivity Center uses purchasing power parity when converting GDP to dollars. Purchasing power parity is calculated at an exchange rate to level Japanese and U.S. living standards. The exchange rate is 155 yen to the dollar for 2000 against 98 yen to the dollar for 2022, indicating the yen’s appreciation rather than its depreciation. This means that goods and services in Japan today are of better quality and can sell at higher prices in the United States. Still, Japan’s labor productivity fell to 31st place in 2022 because Japan has a higher employment rate, with living standards in some European countries being higher than indicated by the euro’s valuation. Therefore, the ranking of labor productivity should be taken seriously.

Why have Japan’s per capita GDP and productivity stagnated over the long term? Having made international comparisons of productivity since the beginning of the 21st century, we feel that structural reforms designed to improve productivity have been abandoned under economic management that has relied on the fiscal and monetary policies represented by Abenomics.

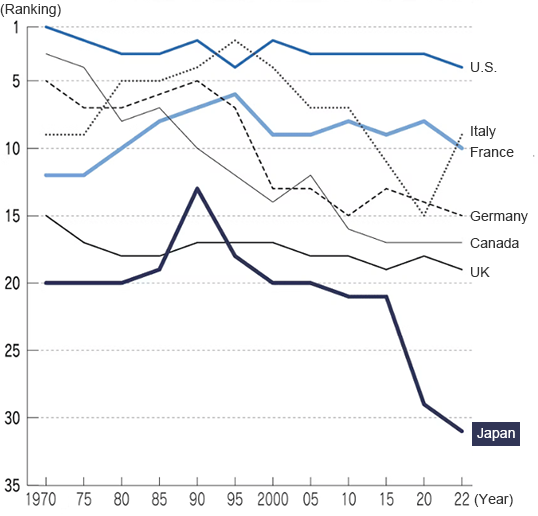

In the past, the government set a goal of realizing one of the world’s most advanced information technology societies. However, we doubt if a society that features the insufficient spread of My Number cards and the absence of ride-sharing services can be called the world’s most advanced society in terms of IT. In fact, the ranking of Japan’s labor productivity has been declining sharply since the middle of the 2010s (see the chart).

Source: Japan Productivity Center

One of the reasons why productivity has not improved is, as is often criticized, that structural reforms are intensifying labor. Unless workers try to acquire new skills, however, both economic well-being and safety may degrade.

When we began to advocate the improvement of productivity as a solution to one of the challenges facing the Japanese economy, there was an expectation that the Japanese economy would eventually rebound. However, the longer-than-expected slump harbingers Japan’s gradual Argentinization.

◆◆◆

Despite being on opposite sides of the globe, Japan and Argentina have a strange connection regarding economic growth. In past discussions on what countries would become developed countries after Western countries did so through the Industrial Revolution, Japan and Argentina were often mentioned as candidates.

Later, Japan was more economically successful than Argentina, contrary to most expectations. Since the beginning of the 21st century, however, Japan has continued to roll downhill in a manner that resembles Argentina. In World Bank labor productivity rankings, Japan fell from 28th in 1995 to 45th in 2022, while Argentina dropped from 44th to 55th.

Argentinization features an outflow of high-quality people, goods, and money. In terms of human resources, Japan's education level is extremely high among developed countries. In sports, Japan and Argentina have produced once-in-a-century players such as Japan’s Shohei Ohtani in baseball and Argentina’s Lionel Messi in soccer. However, they demonstrated their abilities in Western countries. In Japan, the innovative, two-way player might not have been embraced to the same degree. And while Japan’s population has declined, in fact, the number of Japanese permanent residents overseas has continued to increase.

In countries that lack innovation, investment in goods is directed overseas. In order to make money from conventional businesses, it is advantageous for Japanese companies to raise funds at low interest rates in Japan and invest them in foreign countries that feature higher profitability.

Regarding money, Argentina has suffered economic crises due to capital outflows on numerous occasions. Signs of capital outflows are beginning to appear in Japan as well. While Western countries have raised interest rates since 2022, Japan has maintained zero interest rates, leading to capital outflows and the yen’s depreciation.

The outflow of high-quality people, goods, and money will lead to further impoverishment, prompting people ironically to become even more dependent on the government. However, the government itself does not have the ability to revitalize the economy. There is a significant possibility that Japan could enter a situation in which voters say “no” to a bloated, immobilized government, as seen in Argentina.

Is there any way to prevent the gradual Argentinization? One conceivable method is to enhance the implementation of the conventional growth strategy. However, this may be infeasible. Vested interests and regulatory barriers are major reasons for the infeasibility. The protracted economic stagnation have made it difficult for the generation who had no business experience before the 1990s to recognize significant growth after the reforms, making the reforms less convincing.

The generation who began to work during and after the so-called employment ice age has experienced little economic growth and has only seen a stagnant Japanese economy. For this generation, Japan is not a world-class country in terms of economic vitality or science and technology. The scenario of the older generation, which prioritized economic prosperity may not seem attractive to them. They may need to be convinced using a vision that encompasses a richer life experience overall. The Japan Productivity Center’s attempt to explore comprehensive well-being indicators, including productivity, as introduced by Professor Miho Takizawa at Gakushuin University in this column on January 18, seeks to revise the Showa-style orientation towards growth that was prevalent before the 1990s.

A more economic and political approach is the "capital approach" presented in the Final Report of the Independent Review on the Economics of Biodiversity led by Professor Sir Partha Dasgupta at the University of Cambridge. The capital approach considers services that enrich people's lives as including not only services provided by the market economy but also environmental and other non-market services and sets out a policy goal of providing these services by combining private capital, social infrastructure, natural capital, and human capital.

It will take time for this approach to take hold. In the future, GDP, which has always served as a key measure of economic well-being, will change to represent more comprehensive well-being. While it is important to take the GDP and productivity stagnation seriously, a strategy for "well-being" that goes beyond a simple return to the past must be developed.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

February 21, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun