As COVID-19 has been downgraded to a Class-5 infectious disease like influenza under the Infectious Disease Act, the time has come for Japan to fully consider its economic recovery. Economic indicators over the three years of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrate that there was no economic growth in Japan.

In 1956, the Economic White Paper declared that Japan was no longer in a postwar reconstruction phase as the economy had surpassed its pre-WWII level. At present, however, Japan’s annual gross domestic product is still below the 2019 level, indicating that Japan cannot declare that it has exited from the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many Japanese people realized the vulnerability of their livelihoods with the declining technological standards as delays in digitalization and semiconductor shortages appeared during the recovery period. Therefore, there is concern that even if economic stimulus measures are implemented on the demand side, no sustainable growth may be expected due to immediate supply constraints.

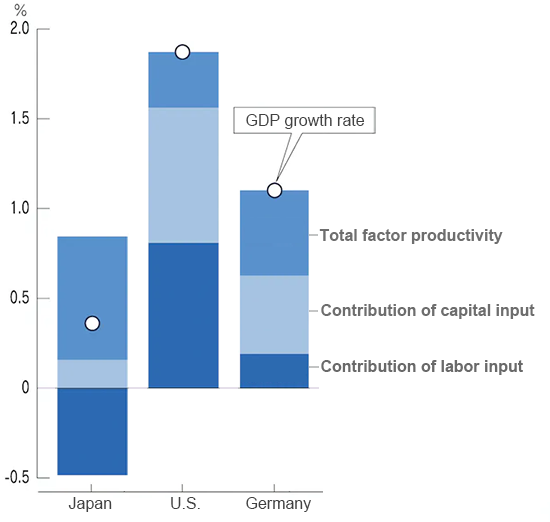

In addition, the decline in the number of births accelerated under the pandemic, making long-term economic growth prospects increasingly pessimistic. Decomposing the economic growth in the last decade into the contributions of labor, capital and total factor productivity (technological innovation) in Japan, the United States and Germany indicates that gaps in labor input between Japan and the other two countries contribute significantly to differences in their GDP growth rates (see the figure below).

◆◆◆

Based on the following two points, however, I believe that there is no need to be overly pessimistic about the future of the Japanese economy.

First, economic growth theories should focus on growth in per capita GDP or income. Due to Japan’s longstanding position as the country with the world's second or third largest GDP, we tend to focus on the size of GDP. However, we should pay more attention to per capita GDP growth.

It is pointed out that per capita GDP in Japan has continued to decline in world rankings. In fact, however, countries that post higher per capita GDP than Japan, excluding the United States, have smaller population sizes than Japan. Given this fact, it can be concluded that Japan has the potential to increase economic affluence further despite future population loss.

Second, Japan is not the only country that has been losing growth potential. Since the 2008 global financial crisis, developed countries have been growing at slower rates than earlier, with significant variety. Apart from the United States, per capita GDP growth rates in European developed countries have stayed around 1%, close to Japan’s. In addition, supply-side constraints have become even stronger in Europe due to the Ukraine conflict. Essentially, Japan is not being left behind other developed countries.

In the 2020s, competition and collaboration that will enhance the supply side are expected to unfold not only in Japan but also in other developed countries.

Per capita GDP growth largely depends on labor productivity growth. Labor productivity growth depends on capital accumulation and total factor productivity growth, which is influenced by technological capabilities. As the figure shows, the combination of capital accumulation and total factor productivity growth in Japan is about the same as in Germany, though it is less than in the United States. Japan can therefore increase per capita GDP by boosting capital accumulation and technological capabilities.

In particular, the sluggishness of capital accumulation in Japan has been remarkable. In the 2010s, Japan tried to create a virtuous cycle from the demand side by taking advantage of wage hikes to stimulate consumption and induce inflation to decrease the real interest rate and eventually increase consumption and investment expenditures. However, the demand-focused economic stimulus policy left the supply side vulnerable while wage hikes failed to materialize.

In contrast, in the 2020s, Japan should first consider an investment-based virtuous cycle. Capital investment will not only strengthen the demand side but also the supply side supported by capital accumulation and will lead to a virtuous cycle in which productivity improvement facilitates wage increases, expanding consumption.

Since the second half of the 2010s, capital investment in construction and in information and communications equipment has increased in Japan. The construction subjected to the investment expansion have apparently included facilities for the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics and for foreign tourists visiting Japan for the event. The rise in investment in information and communications equipment might have been attributable to an increase in telework during the COVID-19 pandemic.

An important question is whether such increases in investment are sustainable. What is worrisome is that growth in software investment has failed to accompany growth in digital hardware investment. Of course, many software products used for business purposes are now largely free, while in many cases software products have moved to a subscription model, meaning that they would not be counted as fixed assets.

I would like to introduce the “Survey on Information Technology and Human Resources that can Improve Productivity,” which I conducted jointly with Waseda University Professor Daisuke Miyagawa and Gakushuin University Professor Miho Takizawa in 2019. The survey, despite its small sample size, found that the ratio of cloud spending to sales stood at 0.12%, which is close to the ratio of information technology hardware spending to sales, at 0.17%.

It is possible that the total factor productivity growth in the 2010s shown in the figure include subscription software, which would not be valued as fixed assets in Japan resulting in such business efficiency gains. Intangible assets are difficult to measure correctly, obscuring the real effects of capital accumulation. In the future, it will be necessary to account for the use of software that is not recorded as a fixed asset in Japan.

◆◆◆

In order to realize a virtuous cycle based on investment, the following two factors are required beyond the promotion of individual investment deals.

The first factor is the realization of a stable inflation rate. Inflation lowers the value of money and makes the corporate sector's retention of cash and deposits accumulated since the early 21st century relatively disadvantageous, which would promote real investment.

The second factor is more active foreign investment in Japan. It has been confirmed through various studies that foreign investment improves productivity by introducing business management capabilities and technologies that are not then available in Japan. Productivity gains will contribute to upskilling human resources and raising wages that continue to be low. Because the government is aware of these effects, it is actively trying to support the expansion of foreign semiconductor companies into Japan.

To spread such government support to other industries, the government should create a centralized foreign investment attraction system akin to the Japan Tourism Agency.

However, the importance of capital accumulation does not mean that the government should continue to enhance its involvement in private sector capital accumulation. While the government has increased its involvement in private sector activities in the face of major crises such as the Japanese financial crisis, the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis, this seems to have created a dependence on the government within the private sector. Once the economy recovers to the level before the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the government should focus more on developing infrastructure that supports private sector growth.

Since the Kishida administration took office, the government has been focusing on supporting human resource development at private companies. However, the foundation of the education system, which is even more necessary for human capital formation, has been shaken. The government should seriously consider that unless the foundation of basic education is reconstructed, all other productivity improvement measures may end up being a house of cards.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

June 19, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun