The latest Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform, released in June 2017, defined human resources (HR) development and productivity improvement as priority policy issues. As someone who has consistently emphasized the importance of implementing measures designed to enhance productivity ever since Prime Minister Shinzo Abe returned to power and formed his second Cabinet, I cannot help but feel that things are finally beginning to happen albeit belatedly.

It is not that the government of Prime Minister Abe has done nothing to implement its growth strategy. Over the past four and a half years, the government has launched reform efforts in the areas of agriculture and tourism. Just recently, Japan and the European Union (EU) reached an "agreement in principle" on an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). Still, there is no denying that the growth strategy has taken a backseat throughout those years with Abenomics centered on monetary policy, i.e., massive quantitative easing under the banner of ending deflation.

♦ ♦ ♦

There are two reasons why the growth strategy has now come to take the center stage in the pretext of improving productivity.

First, monetary policy, which has been the key driver of Abenomics, has reached a dead end with the Bank of Japan (BOJ) running out of magic. Second, on the back of a series of economic stimulus measures implemented to date and chronically low fertility, aggregate demand-supply gaps narrowed and Japan's labor market has tightened to the level it experienced during the bubble years of the late 1980s. In other words, although some goals are yet to be achieved, the government has reached the conclusion that it can no longer afford to rely on pump-priming measures as the key driver of the economy and must focus its efforts on improving long-term growth potential.

When measures designed to promote growth and structural reform are introduced, their effects tend to concentrate in specific areas in the initial stage, with some groups suffering disadvantages until the effects become widespread enough to reach them. Thus, such measures are politically unpopular and inevitably difficult to implement unless the government has been in power for many years and continues to enjoy strong and stable support. However, even with this taken into account, Japan's growth strategy has been unbearably slow to come by.

Indeed, few governments formed since the burst of the bubble have enjoyed long-term stability, and such political instability is one factor. Apart from this, the biggest factor behind Japan's failure to have a solid growth strategy in place is that the information technology (IT) revolution, a game-changing innovation, occurred in the United States and other parts of the world in the second half of the 1990s, just as the effects of the prolonged post-bubble malaise were beginning to manifest in Japan. The problem of nonperforming loans surfaced and paralyzed the banking system exactly at the time when the Japanese economy needed to cope with the new wave of technological innovation.

Both businesses and banks took backward-looking measures to defend themselves. Businesses embarked on restructuring as their top priority and increased their reliance on non-regular workers, i.e., those other than permanent full-time employees. Banks had no choice but to devote their efforts to collecting debts and avoid making risky loans. The situation was in stark contrast to that of the United States, where a number of startups emerged and grew rapidly against the backdrop of the IT revolution.

♦ ♦ ♦

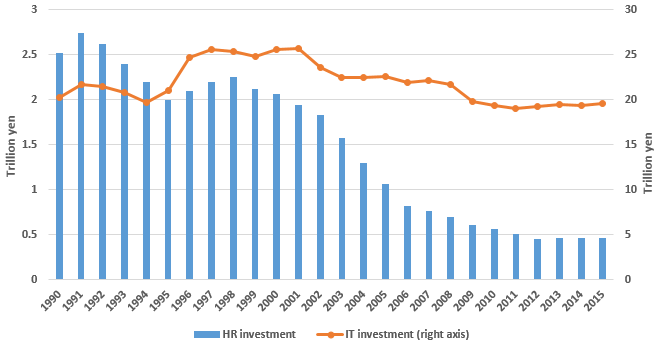

Shown in the Figure are changes in IT and HR investment in Japan since around the end of the bubble economy. The amount of IT investment is the sum of investment in computers and their peripheral equipment, telecommunications equipment, and software. Meanwhile, the amount of HR investment is the estimated cost of off-the-job training based on data on the cost of education and training from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare's General Survey on Working Conditions.

IT investment in Japan plateaued in the wake of the financial crisis in 1997, and has been on a downward trend since 2000. Even more shocking is the trend of HR investment, measured as the cost of off-the-job training. HR investment, which began to drop immediately after the burst of the bubble economy, temporarily recovered but took a downturn to decline more sharply after 2000.

Indeed, many Japanese companies are providing extensive on-the-job training. However, such training is not enough to introduce new technologies into organizations, albeit effective in facilitating the succession and/or improvement of existing technologies.

The Economic Report of the President submitted to the U.S. Congress in 2007 states as follows: "Only when [businesses] made intangible investments to complement their IT investments did productivity growth really take off." Indeed, in a recent empirical analysis conducted with Toyo University Professor Miho Takizawa, we found that IT investment and HR investment have synergetic effects, together contributing to a rise in the return on equity (ROE) by improving productivity.

This research finding suggests that the lack of measures to improve productivity through IT and HR investment has been a major cause of the downward trend in profitability in the past 20 years since the financial crisis. In light of these developments to date, it cannot be avoided to say that it is extremely difficult to achieve productivity improvement comparable to that observed during the bubble period, as assumed by the Cabinet Office in making primary balance projections under the economic revitalization scenario.

What policy interventions should the government make to promote greater utilization of IT and foster HR development? To begin with, government should digitize its ministries and agencies. The Basic Policy on Economic and Fiscal Management and Reform called for promoting the advancement of technology in the private sector. In this regard, the government should make effective use of the data it possesses.

It is probably impossible to realize overnight an e-government comparable to that of Estonia in northern Europe. However, it is quite possible to eliminate much of the documents that businesses and individuals are required to file in various government procedures by establishing a system enabling all government ministries and agencies to utilize and share data with each other. Now that the identification number system for individuals and businesses is in place, collections of data held by government ministries and agencies can evolve into a new form of infrastructure.

When businesses and the government seek to utilize IT in more areas of their operations, a lack of relevant HR stands as the biggest obstacle. As aforementioned, this is the outcome of leaving problems unaddressed for years and there is no quick solution. Ideally, generational transitions and the penetration of technological innovation should take place with the rise of tech-savvy young entrepreneurs—those versed in IT and artificial intelligence (AI)—and the growth of their businesses. However, this process is alarmingly slow in Japan. Given the current pace of adjustments, HR of all generations—including those working for existing companies—must be developed.

Knowledge in data science or an ability to use and analyze data to make judgments is essential. Some universities have already begun to offer data science programs for their current students and those to follow. The same needs to happen and expand at all levels of education. Existing organizations, which employ tech-savvy young talents as workforce, need to establish a system that is receptive to data-based decision making by reforming organizational structures and decision-making processes.

♦ ♦ ♦

At a recent conference held at Hitotsubashi University to discuss the development of a productivity database in Asian countries, enabling the measurement of progress in the utilization of IT and HR in a way that allows international comparison was defined as a key challenge to be tackled in the coming years. It is expected that Asian countries will gear up efforts to measure progress in productivity-related areas as part of basic data on economic growth.

Meanwhile, at a RIETI symposium (cohosted by the Japan Productivity Center and the Hitotsubashi Institute for Advanced Study) held subsequent to the conference, Harvard University Professor Dale W. Jorgenson cited HR development and utilization as one of the key measures to boost productivity in his keynote speech entitled "The Second Phase of Abenomics."

It was unfortunate that the financial crisis forced the entire Japanese economy to take backward-looking measures at a critical point in time, when the IT revolution—a new wave of technological innovation—was occurring in the world. However, post-reunification Germany also suffered stagnation in the 1990s due to the adjustments needed to bridge the gaps between its formerly separate countries. Yet, after the turn of the century, Germany emerged from its stagnation and has now become the best-performing advanced economy, partly helped by the establishment of the EU and labor market reform implemented in the country. Also, South Korea, which was hit by a currency crisis at around the same time as Japan was suffering its financial crisis, has undergone painful structural reform and grown into an economy that embraces global leaders in some industries.

Considering those examples set by Germany and South Korea, Japan must not come to terms with its chronically low productivity and using the unfortunate coincidence in history as an excuse.

* Translated by RIETI.

August 22, 2017 Nihon Keizai Shimbun