Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, newly reelected as head of the Liberal Democratic Party in September 2015, has declared his intention to take Abenomics to the next stage. Whether the new policies known as the "three new arrows" can be achieved depends on the degree to which Abenomics has improved the economy so far and created a foundation for the new policies to be implemented.

Assessing Abenomics is no simple task, in part because the hiking of the consumption tax rate in April 2014 also had an impact. For example, prices have not achieved their target, though this was one of the initial emphases. Consumption and production also have not grown significantly. As a result, gross domestic product (GDP) has not risen that much since the start of the Abenomics policies.

Nonetheless, Abenomics has not come under fundamental criticism, because the labor market has turned around and the weak yen has boosted corporate profits. The new Abenomics aims to address the problem of Japan's low birth rate and improve social security against the backdrop of strong growth, as symbolized by its GDP target of 600 trillion yen. However, a look at Japan's mixed economic indicators shows no grounds for such strong growth.

♦ ♦ ♦

Below, we will examine the impact of Abenomics on the Japanese economy and the feasibility of the new Abenomics through examining Japan's growth potential.

Abenomics has succeeded as far as its first two arrows are concerned: bold monetary policy and flexible fiscal policy. However, the third arrow, a growth strategy, has not been sufficient. This suggests that the main policy of Abenomics was to stimulate aggregate demand. It is puzzling that, although the policies to stimulate aggregate demand narrowed the supply and demand gap faster than expected and improved the labor market, GDP growth remains as slow as it was before Abenomics.

The key to solving this puzzle is to consider the decline in growth potential which is the supply-side factor. Generally, a decline in growth potential is considered to be caused by the decreasing working population. However, the decline in Japan's working-age population started in the mid-1990s; it is not a recent phenomenon. Therefore, the decline in capital accumulation due to sluggish capital investment has to be considered as well.

The Cabinet Office's Quarterly Estimates of Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises is used to calculate the supply and demand gap. In the statistics, capital is assumed to be kept in use as a factor of production unless it is physically removed. If we take this approach, then any equipment would maintain its initial production capacity at the time of its purchase. Therefore, the capital stock that appears in the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises is constantly increasing.

However, you could also think of the production capacity of old machines as declining over time. For example, personal computers gradually lose their relative processing capacity. Taking this stance, researchers who study productivity universally judge productivity and growth potential based on "productive capital stock." The Japan Industrial Productivity (JIP) Database, run by the Institute of Economic Research at Hitotsubashi University and RIETI, takes the approach close to the concept of productive capital stock. According to the JIP Database, the capital stock of the private sector (market economy) of Japan peaked in 2008 and then started to decline.

♦ ♦ ♦

Therefore, we examined the degree to which the supply and demand gap appears depending on the differences in capital stock.

We employed the approach to estimate the supply and demand gap based on that of the Cabinet Office, which was described in "The GDP Gap and Potential Growth Rate since the 1980s" by Tetsuro Sakamaki. As the estimates in the JIP Database are available only through 2011, we extended the estimates using capital investment in Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises and the real fixed assets balance in the National Accounts of Japan, keeping in line with trends in the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises and converted to a quarterly basis.

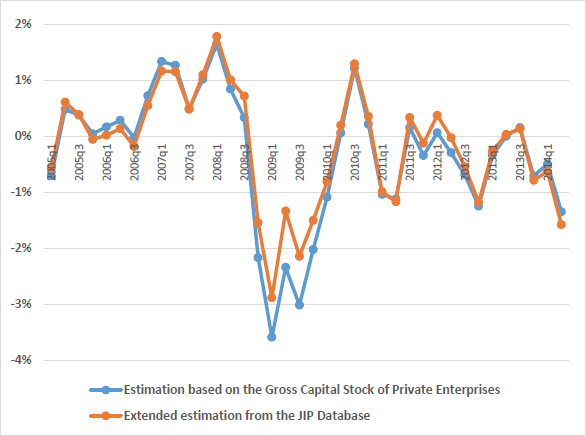

There is a big difference in the amount of capital stock calculated based on the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises and the extended estimation from the JIP Database. In comparing the supply and demand gap using the two sets of capital stock statistics, there is a tendency for a negative gap to appear smaller during recessions and a positive gap to appear somewhat larger during boom periods when using the latter rather than former (see figure).

The supply and demand gap during the period after the global financial crisis and just before the start of Abenomics (between the second quarter of 2009 and the fourth quarter of 2012) was clearly smaller when using the JIP Database than the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises, narrowing the gap up to 1%, or about five trillion yen.

Rates of technical progress differ in the two estimates: 0.1% for the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises and 0.57% for the JIP Database respectively. If the supply and demand gaps are calculated using the same rate of technical progress, the difference between the one based on the former and the one based on the latter would grow to 40 trillion yen.

In other words, as potential production capacity appears lower in the estimate based on the JIP Database than the one based on the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises, when measures to stimulate aggregate demand are taken, the supply capacity reaches its upper ceiling immediately. This is consistent with the persistent mild deflation before Abenomics and the sluggish growth in GDP since then.

The reason why only the labor market has improved is that firms considered the increase in aggregate demand as a temporary phenomenon, thus responding by increasing the labor force rather than capital. This is also clear by the fact that the ratio of non-regular employment continued to rise in spite of the improvement in the labor market. Moreover, if people see Abenomics that has been implemented so far as a short-term policy of increasing aggregate demand while long-term supply capacity declines, they will not change their future inflation expectations.

In response to such view, some may say that there is nothing to worry about because the difference between the two supply and demand gap rates has been disappearing recently. But looking out into the future, there is a big difference depending on whether or not we consider the recent stagnation of supply capacity. Growth in capital stock during the 2010s has been no more than 0.1% using the JIP Database (1.9% with the Gross Capital Stock of Private Enterprises).

Taking into account of the weakness in supply capacity, wherein not just labor but also capital accumulation is slow, the new Abenomics, based on the assumption of 2% growth potential, anticipates achieving a technical progress rate that is roughly equivalent to the growth potential over the medium to long-term. Japan has not achieved such a high technical progress rate for a very long time—since the end of the bubble economy—and it is far from having drawn up a growth strategy that would allow us to achieve such a high rate again.

♦ ♦ ♦

After the collapse of the bubble economy, the Japanese government failed to tackle the problem of non-performing loans, instead, trying to prop up the economy with massive public investment. It also overestimated the birth rate, thus putting off the problem of paying for social welfare to a later time. Policies based on this optimistic view of the future delayed action on the subsequent financial crisis and social welfare issues. For these reasons, the Japanese economy is under a heavy burden today, especially in terms of its fiscal situation. Now again we have an ambitious policy based on a bullish growth outlook, but there is a risk of repeating the past experience.

What the government should be doing first is carrying out reforms in the improving labor market with a focus on stepping up supply capacity. It should try to organize a fluid labor market so that workers can work and be rewarded according to their abilities. It is also necessary for firms to change their conventional way of thinking about capital investment in response to increasing demand. In responding to the decreasing working-age population and markets change, they need to transform their business model and shift to an investment strategy that enhances profitability, such as IT investment. If we aim for a sustainable Japanese economy, the only choice left is to face the realities and implement down-to-earth policies.

* Translated by RIETI.

October 6, 2015 Nihon Keizai Shimbun