After the amendment of the Labor Standards Act in April 2019, a cap was imposed on overtime work. In this piece, I'll initially outline the changes made to address the prevalent issue of extended working hours in Japan following the legal amendment. Subsequently, I intend to explore the prevailing discourse surrounding the '2024 problem,' an issue that has garnered substantial attention of late.

The 2019 amendment to the Labor Standards Act mandates that annual overtime work for any employee must not exceed 720 hours, even in exceptional or specific circumstances (this requirement was implemented for small and medium-sized enterprises in 2020). This annual ceiling translates to a maximum of 15 hours of overtime work per week, calculated by dividing 720 hours by (12 months x 4 weeks) = 15 hours. Assuming a standard workweek duration of 40 hours, this caps the maximum weekly working hours at around 55 hours.

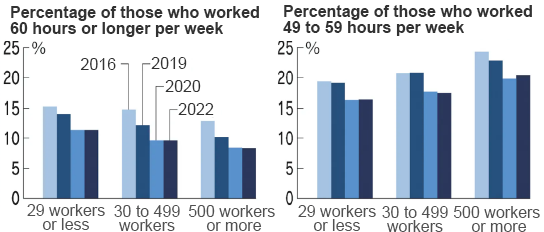

To accommodate varying workloads, I established a threshold of 60 hours per week and generated a chart illustrating the percentage of male employees working 60 hours or more per week categorized by company size, displayed on the left in Figure 1. Following the implementation of the working style reform initiative in 2016, there was a decrease in the percentage of overtime workers by 2019 and 2020, further declining after the Labor Standards Act amendment, although the rates differed among company sizes. The percentage of workers putting in 49 to 59 hours per week, depicted on the right in Figure 1, also decreased from 2016 to 2020 and stabilized thereafter. Notably, at larger companies, the working hours seemed to hover just below the 60-hour threshold, potentially indicating employer efforts to maximize work hours while staying within the regulatory limit.

In 2021, although not represented in Figure 1, the percentage of overtime workers remained consistent with the levels observed in both 2020 and 2022. This indicates that despite the emergence and acceptance of diverse working styles during the COVID-19 crisis, the rectification of prolonged working hours did not progress significantly. While the overall trend shows a decline in the percentage of workers putting in 60 hours or more per week, suggesting some positive impact from the amendment to the Labor Standards Act, nearly 30% still exceed two hours of overtime daily, even five years after the amendment. This illustrates that Japan is only midway through its efforts toward working style reform.

In connection with regulations on overtime work, the '2024 problem' has become a frequent topic of discussion. As per the 2019 amendment to the Labor Standards Act, doctors, professional drivers, and construction workers were provisionally exempted from the overtime work regulations due to the distinctive nature of their work and related business practices. The '2024 problem' denotes the concern that our society might encounter various repercussions when the types of jobs previously exempted from overtime work regulations become subject to them starting in April 2024.

◆◆◆

These particular job sectors consistently face significant shortages in available labor. If strict regulations on overtime work are imposed in these job sectors struggle to secure adequate manpower to handle the existing workload with reduced overtime, it could lead to an increased number of companies going out of business. Such a scenario could significantly impact the critical social infrastructure that supports our daily lives. In July 2023, media attention surged when high-ranking officials overseeing the 2025 international expo in Japan (Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai) urged the government to exempt expo-related construction work from the overtime work regulations.

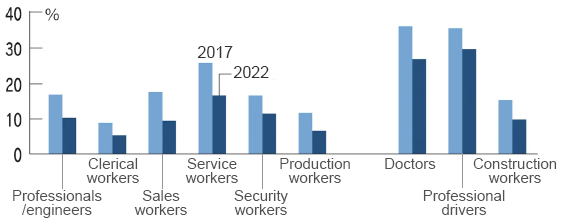

When comparing the overtime work in occupations set to fall under the overtime work regulation in 2024 with other job types, the extent of overtime hours stands out. Displayed on the left side of Figure 2 is a comparison showing the percentages of workers putting in 60 hours or more per week across six broad job categories in 2017 and 2022. Over the past five years, there has been a consistent decline in the percentage of overtime workers across all job categories, although the rates vary significantly among them. In 2022, while the percentage of clerical workers engaged in overtime dropped to 5%, more than 17% of workers in service sector logged 60 hours or more per week.

Featured on the right side of Figure 2 are the percentages of overtime workers among doctors, professional drivers, and construction workers who, after the provisional exemption period, will come under the purview of the overtime work regulation, forming the crux of the 2024 problem. Over the past five years, the percentage of extreme long-hour workers (those working over 60 hours per week) in these three job categories has decreased, reflecting employer efforts to address prolonged working hours during the exemption period. However, in 2022, 27% of doctors, 30% of professional drivers, and 10% of construction workers continued to work 60 hours or more per week. Moreover, the percentage of those putting in 70 hours or more was notably high, reaching 14% among doctors and 11% among professional drivers.

It's important to highlight that when the provisional exemption from the overtime work regulation ends in 2024, construction workers will fall under the same annual upper limit of 720 hours as applied to other occupations. However, for doctors and professional drivers, the upper limit for overtime work will be set at 960 hours per year. In short, beyond 2024, despite the application of overtime regulations to doctors and professional drivers, their upper limit will still be higher compared to that set for other worker categories.

Additionally, concerning doctors, there's a possibility of raising the upper limit for overtime work to 1,860 hours per year under special circumstances, granted when hospitals apply for and receive approval for a heightened threshold. This increased annual limit would equate to a monthly ceiling of 155 hours, calculated simply by dividing 1,860 hours by 12 months. Notably, this far exceeds the critical threshold often referred to as the 'karoshi (death from overwork) line,' which stands at 80 hours per month.

While this special measure remains an option, it's crucial to expedite the implementation of healthcare system reform measures currently under consideration. These initiatives aim to reduce working hours for doctors and other healthcare professionals through various means, including task shifting, the introduction of nurse practitioners and other innovative job categories, and the consolidation of regional healthcare institutions.

Some argue in favor of subjecting doctors to the discretionary working system or the high-level professional system, considering their professional expertise and income levels. However, an analysis based on data from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare's Survey on the Actual Status of Discretionary Working Arrangements reveals significant variations in the impact of these systems on workers' working hours and their mental and physical health. This variance is rooted in the level of discretion individuals possess in managing their work responsibilities, which can significantly affect their well-being. Importantly, despite being legally obliged to provide medical services upon request, many doctors have limited discretion in their work schedules. Therefore, when considering the implementation of discretionary working arrangements, it's crucial to assess whether individuals genuinely possess the discretionary power to adjust their work schedules.

◆◆◆

In July 2023, the jobs-to-applicants ratio (excluding part-time workers, focusing on regular employees) stood at 2.72 for professional drivers, 5.89 for construction workers, and 3.03 for doctors, notably higher than the ratio of 0.32 for clerical workers. This highlights a persistent and severe labor shortage specifically within the job sectors central to the 2024 problem.

The evident aging trend within the professional driver and construction worker demographics presents an additional significant challenge. Data from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare's Basic Survey on Wage Structure reveal a concerning pattern: while approximately 50% of all male workers are aged 44 or younger as of 2022, this figure significantly drops among truck drivers, plummeting from 46% in 2012 to a mere 27% in 2022. At a time when attracting young workers to the logistics and construction industries is challenging, the impending tightening of overtime work regulations may not only strain existing manpower to cover workloads but also exacerbate labor shortages due to the reduction in overtime pay.

In theory, addressing the labor shortage should involve wage increases. Over the past decade, door-to-door parcel delivery charges have surged by approximately 17%. Despite this, the average hourly wages for truck drivers aged 35 to 39 have only seen a 9% increase within the same period, positioning their wage level approximately 20% below the average for the same age group across all professions. With the persistence of extended working hours and relatively low wages, it's unsurprising that young workers are disinclined to join the trucking industry.

Over the last three decades, Japanese companies have refrained from increasing prices, fearing potential customer alienation. Simultaneously, they have faced challenges in raising wages. Operating under the premise that neither wages nor prices should rise, companies have remained locked in intense competition, compelling employees to endure long working hours to sustain quality customer service. Despite concerns about inflation stemming from prolonged yen weakness, Japan, which has long grappled with mild deflation, generally does not embrace price hikes. However, with the continued aging of the labor force, the traditional Japanese business model centered on the ethos of 'where there's a will, there's a way' has encountered its limitations.

Accidents resulting from overwork in critical sectors like healthcare, transportation, and construction, due to labor shortages, can lead to tragic consequences. If critical lifeline infrastructure services, including logistics, construction, and healthcare, are undermined, it will be the Japanese people who must bear the cost. Recognizing the value of quality services must align with fair compensation, we need to change our mindset and accept the idea that price increases and wage hikes are essential. While initiatives aimed at enhancing work process efficiency and leveraging information technology to reduce manpower are being explored, societal change in perspectives toward pricing and wages holds greater importance.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

September 22, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun