In 2020, the global labor market was forced to undergo dramatic changes. The greatest change is probably the shift to teleworking (working from home, hereafter WFH). In Japan as well, this new working style rapidly spread after the declaration of a state of emergency in April amid the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis. Some types of job may not be suited to WFH. From recent experiences, however, even those who engage in jobs that have been considered to be unfit for remote work, found it easier than expected to work from home. According to some questionnaire surveys conducted in Japan (e.g., a survey by the Cabinet Office [2020] and a survey by the Japanese Trade Union Confederation (Rengo) [2020]), many people wish to continue working from home. In Japan, this was likely the first time for many people to experience WFH, but most of them got a first-hand feel of its merits.

However, even though many workers may wish to work remotely, companies are unlikely to be willing to introduce the new working style if it lowers productivity. As a matter of fact, according to a survey conducted by the Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JILPT) (2020), the percentage of WFH sharply rose temporarily, peaking in the second week of May, but started to decline after the lifting of the state of emergency at the end of May, and had declined steeply by the end of July. One presumed reason behind this is that many companies shifted employees to WFH as an emergency measure in response to government requests but returned them to the normal working arrangement early because of concerns over the decline in productivity that occurred during that period.

What conditions and policies are necessary for companies to promote WFH without lowering productivity? According to a survey conducted by Morikawa (2020) in June 2020, on average, the productivity of remote workers during the COVID-19 crisis was 60 to 70% of the productivity of employees working in the office. In particular, the survey showed that the productivity of people who started WFH after the onset of the COVID-19 crisis was substantially lower than those who had been working from home since before the crisis. In order to foresee how the Japanese labor market will change in 2021 and beyond, it is important to examine how much WFH has spread and how that may affect productivity. In what follows, we will outline some of the tentative findings of our on-going analysis on WFH using information collected from surveys on employees of four major Japanese manufacturing companies. This work is conducted jointly with Professor Okudaira Hiroko of Doshisha University and Kitagawa Ritsu of the Graduate School of Economics at Waseda University.

Working from Home after the Declaration of a State of Emergency and Productivity

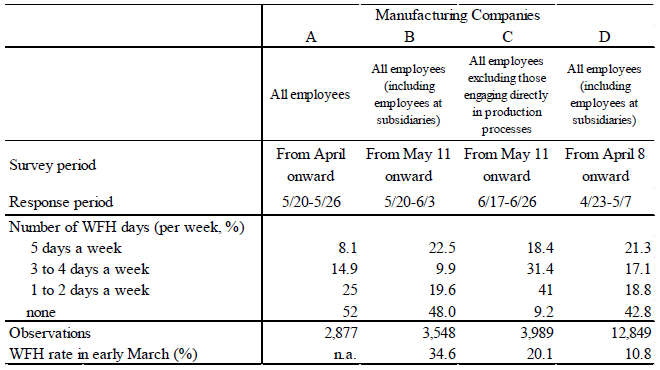

This survey was conducted between April 2020, when a state of emergency was declared, and June 2020, with the cooperation of four major manufacturing companies. The survey was asked to all employees (Companies A, B, and D) or all white-collar employees (Company C). Table 1, which shows the outline of the survey results, indicates the percentage of employees who did WFH by number of days worked from home per week on a company-by-company basis. This shows that among employees within the same company, there is variation in the WFH days. Moreover, the percentage of full WFH workers, or those who worked from home five days a week, ranged roughly from 10% to 30% across companies.

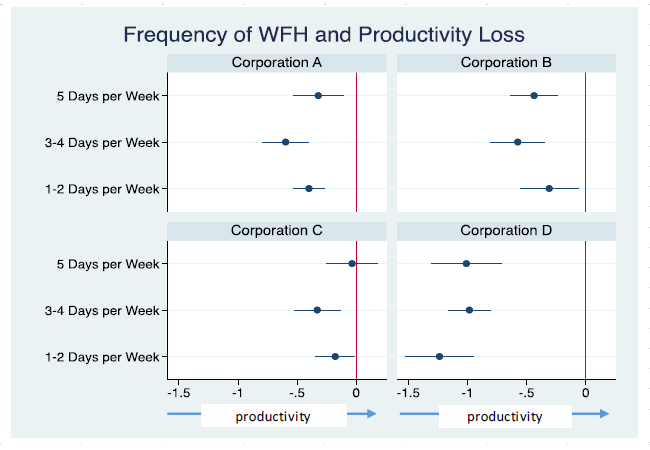

First, we compared the effects of the extent of use of WFH on the level of productivity. Here, productivity was measured based on answers to the questionnaire in reference to the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ), which is used to measure subjective productivity. Figure 1 shows the results. This figure indicates the changes in productivity of a group of WFH employees (separated by the number of days worked from home per week) after the declaration of a state of emergency compared to that of a group of employees who did not (non-WFH group). The red vertical line around the center of each graph represents the productivity level of the non-WFH working group. The location of the circle in the graph indicates how much the productivity of each WFH subgroup diverged from the productivity of the non-WFH group. The horizontal line piercing the circle represents the statistical confidence interval. If the horizontal line intersects with the red line, that implies there is no statistically significant difference between the two groups, while if the two lines do not intersect, that means there is a significant difference. The figure shows that the productivity of the WFH group declined more than the productivity of the non-WFH group did, although there is a variance across companies, with the margin of difference ranging from around 5 to 10 percentage points. In the case of Company D, the decline in productivity is large compared with the other three companies. One possible factor behind this anomaly is the timing of the company's response to the questionnaire, which was late April, two weeks after the declaration of a state of emergency.

What Lowers Productivity?

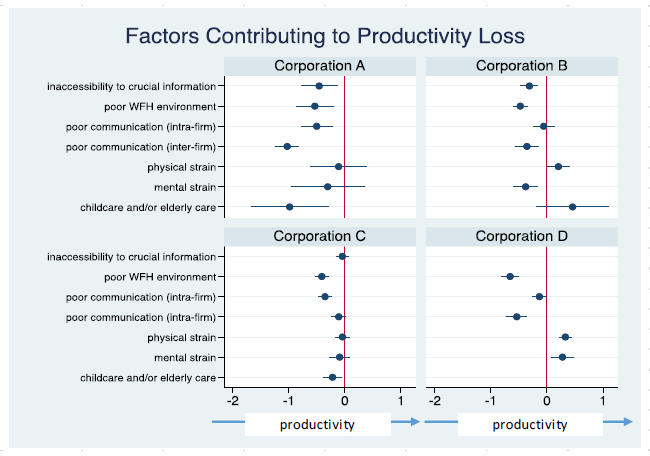

To examine what causes a productivity decline, We used the responses to the following multiple-choice question "what factors, if any, do you think lowers work productivity?" Here, we limit samples to those who worked from home during the survey period. Figure 2 shows the results of regression analysis examining how productivity-lowering factors perceived by the respondents are correlated with productivity changes. The common factors found to be significantly associated with productivity decline in all four Companies are "poor WFH environment at home" and "poor communication" either within the company or with the outside such as clients and customers (Note 1). The former factor may be regarded as underdevelopment of tangible infrastructure, while the latter may be considered as underdevelopment of intangible infrastructure. In short, this finding suggests that it is not WFH itself that lowers productivity, and that developing tangible and intangible infrastructure can restore productivity.

Naturally, the decision on whether or not to introduce WFH should not depend on productivity alone. It is also important whether employees wish to work from home. On this point, the questionnaire for employees at Company A included the question "How frequently would you like to work from home after returning to the normal working arrangement?" According to the survey results, of the 1,381 employees who had experienced WFH, only 7.2% chose the answer "would not like to use," while 52.3% selected the answer "once or twice a week." As much as 22% chose the answer "more than three times a week."

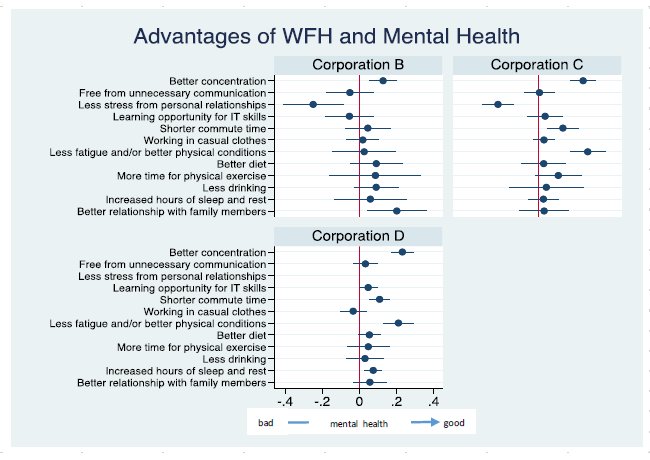

As a matter of fact, our survey found that at all four companies, WFH group reported a better mental health, higher work engagement and less stress than non-WFH group . In relation to the findings concerning those matters, Figure 3 shows the results of analysis of the factors that influenced mental health positively. In this figure, the nearer to the far right of the horizontal line the circle is located, the better the mental health condition is. "Improved concentration" can be pointed out as a factor common to Companies B, C, and D. Regarding Companies C and D, "less fatigue and better physical conditions" and "shorter commute time" are also factors leading to improvement in mental health. With respect to these two companies, it was also separately confirmed that an increase in sleeping time has a strong correlation with mental health improvement and stress relief. As indicated above, improvements in mental and physical health due to increased mental concentration and relief from fatigue were observed among many employees, suggesting the possibility that promoting WFH may lead to an increase in productivity and health enhancement at the same time.

New Style of Working—Outlook on 2021

The findings that the main cause of a productivity decline is an underdevelopment of the necessary infrastructure and that many people feel increased mental concentration and improvements in mental and physical health as benefits of WFH suggest the need for companies to actively make investments to improve the working environment at home and continue to provide a choice of WFH as a working arrangement option.

As mentioned at the beginning of this column, many people voiced the desire to continue WFH, and this desire is not only common in Japan. According to a questionnaire survey (Eurofound [2020]) conducted with workers in EU member countries, around half of people working from home experienced remote working for the first time during the COVID-19 crisis. When asked the preference regarding work from home if there were no COVID-19 restrictions, 32% of all respondents expressed wishes to work from home a few days a week and 13% indicated they would like to work from home every day, while the percentage of those who did not wish to work from home was only 22%. WFH style may take root around the world as a new working style.

Under these circumstances, companies should not dismiss remote working out of hand as a working arrangement option because of lower productivity compared with in-office work. Rather, what they need to do is to conduct a detailed analysis regarding the cause of the productivity gap, make the infrastructure improvements necessary for raising the WHF productivity, and send a clear message from the top management. Presumably, many companies introduced WFH in April as an emergency measure and then took a wait-and-see stance toward infrastructure development. If the top management's commitment remains insufficient, that also affects the stance of the employees toward investment necessary for WFH.

As of early December in 2020, when we are writing this column, the number of COVID-19 infection cases is trending upward in Japan, and the uncertainty over the future will continue for a while after the start of the new year. One encouraging prospect is that after the acceleration of progress in the development and diffusion of ICT tools necessary for the activities that allow for remote working—such as holding online meetings, facilitating communication between employees, and managing business progress—further progress is expected in the future. In addition, as a result of the spread of WFH, working style reform measures, including streamlining of business operations, a shift to paperless procedures, and automation, which have until now made little progress, are starting to take root in the workplace. Further progress in these changes, which complement remote working, will promote more flexible working styles. The changes will create opportunities for people who have been unable to work full-time or work as regular employees—who are supposed to be willing to make business trips or accept workplace transfers—because of time constraints resulting from life circumstances, such as having to raise children or care for the elderly or suffering from illness or a disability. In the medium to long term, the changes are also expected to lead to the narrowing of inequality between regular and non-regular employees.

For the entire world, 2020 was a very challenging year. We hope that the long-held notion that the traditional working style is the best one will be discarded, and that everyone will contribute ideas so that a better remote working environment can be realized.