Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, working styles have undergone dramatic changes across the world. Will the new working styles, referred to as the "new normal," take hold in our society? This article observes the working style changes that have occurred over the past year and considers new issues for debate related to the work-style reform, especially the correction of the practice of long working hours that Japan has been pursuing for the past several years.

♦ ♦ ♦

One of the major working style changes over the past year is the spread of working from home, also known as telework. Although promoting telework has been characterized as a priority challenge of the workstyle reform, the percentage of workers engaging in telework remained low, until it suddenly became widespread after Japan's first declaration of a state of emergency in April 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

The situation was similar in other countries. For example, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics's National Compensation Survey, the percentage of workers who were allowed to engage in telework was only 7% as of March 2020. A European survey (Eurofound) also reported that around half of all workers who worked from home amid the COVID-19 pandemic were experiencing telework for the first time. Nevertheless, several surveys conducted in Japan, the United States and Europe all showed that many workers had a favorable view of working from home and wished to continue telework after the containment of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In response to workers' favorable view, there are moves around the world to allow telework as a new working style. On the other hand, however, there is also strong support for a return to office work. In Japan, the percentage of workers engaging in telework was sluggish under the second and third declarations of a state of emergency. One underlying factor may be the presence of strong prejudices that working from home is nothing more than a temporary measure and that the traditional method of communicating with colleagues and customers face-to-face in the same space represents the best working style.

Telework is sometimes referred to as a "flexible workplace benefit." Flexibility of the workplace is a benefit for workers, and going forward, offering such flexibility will become an important condition for employers aiming to attract highly productive workers. If telework becomes widespread, the door to becoming a regular employee will be opened for people who have until now found it difficult to meet the necessary requirements, such as working long hours, making large numbers of business trips and accepting regional transfers, because of various factors, including the need to look after children or parents, illness, or disabilities. Japan, given its ever-dwindling labor force, should actively develop the telework environment.

Of course, as has already been pointed out, it should be kept in mind that telework tends to blur the line between work and life. The government's guidelines for telework, announced by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in March 2021, allow companies to take a flexible approach to the treatment of off-work time, an issue particular to telework but, at the same time, called for them to take measures to control long working hours, including restricting the use of email and access to computer systems, and to maintain the practice of ensuring the health of workers through management of working hours.

However, even though employers may keep track of working hours through pc logs, it is difficult to strictly manage the work hours of employees who are working remotely. In the future, it will become necessary to change the existing worker management practice, under which ensuring the health of workers depends mainly on companies engaging in management of working hours.

Ensuring the health of workers through working hours management will become more and more difficult due to an increase in gig work, which represents another working style change. Even if companies strictly manage employee working hours, workers' total working hours increase if they engage in side jobs in their off-time.

There is no statistical dataset that strictly keeps track of the number of gig workers in Japan, but the number of people registered with companies operating platform services has increased steeply over the past one year. According to an analysis by Associate professor Atsushi Kawakami at Toyo University, using the Family Income and Expenditure Survey, the percentage of households with two or more persons that had side-job incomes has increased steeply since April 2020. These findings indicate the possibility that in Japan, too, the number of gig workers has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

It is difficult to keep track of the situation of gig work, which can be performed on a one-off basis based on the personal scheduling preferences of the worker, through traditional statistical datasets that are focused on investigating whether or not workers engaged in work in particular time period. As the definition of "gig" is ambiguous, it is difficult to identify the overall number of gig workers even in countries where gig work became widespread relatively early.

Previous studies conducted over the past decade in the US and European countries can be categorized into those which used data from direct surveys with workers, those which used data provided by individual platform operating companies, those which used data from records of payments made via bank accounts and payment apps, and those which used taxation data. However, as these categories of studies have different data inputs, the total number of gig workers differs widely across various studies. For example, the studies conducted in the United States, the figure varies from several percent to 30 percent of the total workforce. In Japan in particular, there have not been many quantitative studies.

♦ ♦ ♦

Below, I will explain some of the results of a survey that I conducted jointly with Yuichi Hasegawa, Kaito Ido, and Shino Kawai, who are students of mine at Waseda University. The survey, which was conducted between October 2020 and January 2021, collected information from 188 Uber Eats delivery workers about various matters, including working time and income. It should be kept in mind that our study focused exclusively on gig workers engaging in a particular type of work—delivering foods through a particular platform—and that the sample number is limited.

From the survey, we obtained the following findings. First, 64% of the workers surveyed had a "main job" other than the Uber Eats work, and around 60% of those who had a "main job" were full-time employees.

Second, the most popular reason for starting to engage in gig work (a multiple-answer question) was a "lack of sufficient income" (48%), followed by "for the sake of interest or physical exercise" (32%), and "loss of the previous job" (17%). The percentage of respondents who cited low income and job loss as reasons was higher among the respondents who started to engage in gig work since April 2020, when the first declaration of a state of emergency was issued, than among those who had been doing so since before then. The finding that gig work has the function of mitigating a steep income decline in times of recession is consistent with the results of past foreign studies.

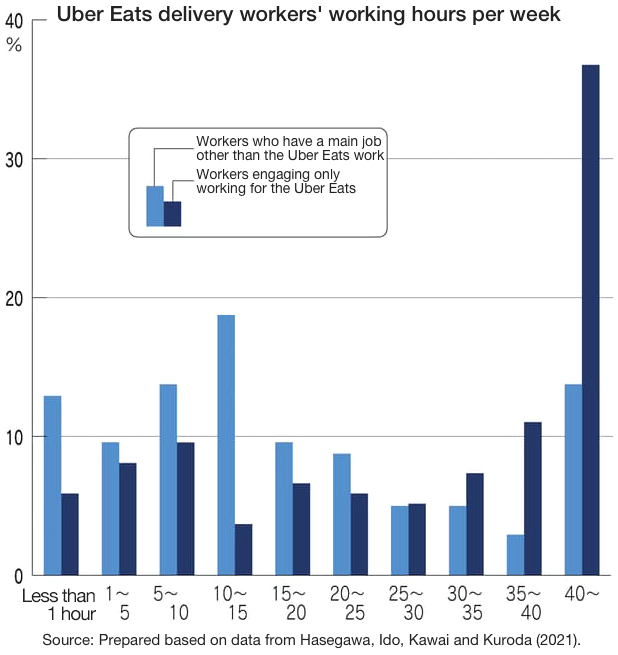

Third, the number of working hours per week varied widely, ranging from less than one hour to more than 40 hours and averaging 23.0 hours per week. The figure shows the difference in the number of working hours between those who had a main job and those who did not. The average number of working hours was 18.7 hours per week for those who had a main job and 16.8 hours per week among those who had a main job and who worked elsewhere as a full-time employee.

Fourth, when we asked respondents about the numbers of working hours and days in the week leading up to the survey and the previous week, approximately half of respondents reported that they significantly changed those numbers from week to week. This indicates that gig workers are flexibly adjusting labor supply in accordance with their own schedule preferences and circumstances, including the weekly demands of their main job.

Around the world, lively debate is ongoing on the status of gig workers as employee. Whether or not gig work will take hold in Japan will also depend significantly on the development of legal frameworks. We must be aware that, in addition to telework, gig work, which enables people to work in time slots of their own choice, is likely to provide Japan with a tailwind as it tackles a deepening labor shortage. If flexible working styles such as telework and gig work spread further, it will become inevitable to change the mindset of companies ensuring the health of workers through working hours management.

While we must prevent Japan from once again becoming a society addicted to long working hours, it is important to change our mindset and explore ways of ensuring the health of workers that are suitable to new working styles, rather than rejecting flexible working styles to prevent the return to the old practice.

The key to changing course is the concept of making sure that workers get adequate rest. Instead of applying a universal method of working hours management to all workers, companies are required to provide health management support tailored to individual workers through the use of information technology (IT), such as giving workers who tend to work too hard a subsidy to cover the cost of using a sensing device that manages the quality and quantity of sleep or health management apps that encourage light exercise and rest from time to time while working.

* Translated by RIETI.

June 8, 2021 Nihon Keizai Shimbun