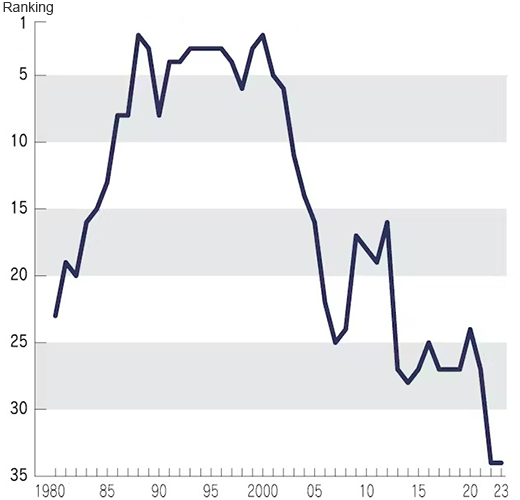

Japan’s per capita gross domestic product ranking has fallen from its top position among the Group of Seven major countries and been overtaken by those of other countries that had been far behind Japan in terms of economic power, currently holding 34th place in the world. Over the past two decades, Japan has changed from a role model for growth to a cautionary tale about stagnation.

As Japan’s working population has decreased due to the declining birthrate and with the marriage rate falling, there is increasing diversity in family structure across the country. While people’s values and codes of conduct have changed along with labor markets and socio-economic environments, Japan has lagged behind other countries in updating its government policies amid the rapid technological advances around the world and has been left behind in terms of economic growth.

Recycling ad hoc policies without addressing changes will not lead to sustainable growth. Outdated policies hinder economic activity and structural growth. In order to achieve sustainable growth, Japan should make a shift based on a long-term perspective.

As the population continues to decrease, the economy will decline if the productivity of each individual is not improved. It is important to encourage women and the elderly to work, but their labor force participation rate is in fact already high, so efforts to increase their labor force participation rate alone will not lead to sustainable growth.

It is also necessary to improve the environment for enhancing individual worker productivity by correcting the gender-based wage gap and facilitating labor mobility, but these efforts alone will not be sufficient to deliver sustainable growth. Japan must remove existing barriers that dissuade individuals and companies from striving toward growth and accelerate investment in human capital and skill development.

◆◆◆

Harvard University Professors Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz point out that the United States maintained a strong economy until the second half of the 20th century by making high school education compulsory, raising the level of human capital in the 1930s ahead of other countries.

With an abundant supply of high-skilled human resources, technological development created wealth without increasing economic inequality. Conversely, if educational level and skill improvement are allowed to stagnate as has occurred in the United States since the 1980s, technological innovation leads to wider inequality and the benefits of economic growth are not shared, leading to a greater concentration of wealth.

Japan’s education system has remained essentially unchanged since secondary education became compulsory just after World War II eighty years ago. The high school enrollment rate has reached almost 100%, but preparation to enter high school or university is largely dependent on the economic strength of parents, and the financial and time burdens of education are only increasing. The university enrollment rate is about 60% and is strongly correlated with parent educational background and income, and community income levels. Thus, inequality spans generations, dividing society to a large extent.

It would be a major change, but Japan could make high school education compulsory and create an environment where every student is able to pursue higher education if they wish to do so. Taking maximum advantage of information and communications technology to promote measures including efficient credit transfer would be of great benefit.

It may seem counterintuitive to extend the compulsory education period and raise the minimum working age in the midst of severe labor shortages; however, in Japan the average number of years worked has been increasing despite the rising rate of university enrollment. Higher lifetime productivity and earnings would lead to greater macro labor force and higher individual lifetime income.

In fact, putting young people into industries with no income growth is a loss for those individual workers and the national economy as a whole. In nursing care, healthcare, and other sectors with severe labor shortages, it makes sense for the government to spearhead focused investment in alternative technologies. Such investment is important from the perspectives of personal income growth, labor force enhancement, and social security spending control.

Demand for highly skilled human resources will continue to increase in line with technological development, and stagnation in the supply of human resources will widen the wage gap. Additionally, while expanding the introduction of foreign workers has been discussed, it is difficult to attract a sufficient number of foreign high-skilled human resources with the average wage level of university graduates in Japan. The same issue is true for highly skilled Japanese human resources, which are also highly mobile. Excessive income redistribution will lead to an outflow of skilled human resources to overseas markets and a decline in the willingness to invest in skills.

◆◆◆

Support for low-income groups and security in retirement are important. In Japan, however, the elderly hold the largest average asset values, while people in their 20s to 50s suffer the most poverty. Taxing working households to pour public funds into an affluent retirement for the elderly should not be Japan’s top priority. The repeated pork-barrel spending on resident tax-exempt, low-income households under the auspices of supporting low-income groups mostly benefits the wealthy elderly, widening inequality.

Support for the poor should be narrowly targeted through conventional channels, such as welfare. If welfare is not functioning well, the solution should be to improve the institution and not pork-barrel spending on the elderly. The stipend program amid the COVID-19 crisis when every moment was critical was significant to some extent, but why is the indiscriminate distribution of benefits continuing five years after we became acutely aware of the need to keep track of those who are afflicted by poverty and in need of relief?

Structural stagnation of the economy is different from an economic crisis. It is irresponsible for the government to provide benefits and subsidies at enormous administrative costs in the name of economic stimulus while praying for growth. Temporary increases in government spending and consumption actually hinder sustainable growth.

Why is that so? It is true that people whose incomes temporarily increase due to peacetime stipend payments increase their consumption, benefiting producers, but if supply cannot meet the growth in demand, prices increase while the tax increase that provides the source of the benefits is postponed. A sudden increase in demand due to a temporary stipend program does not create incentives for companies to increase production or employment over the long term.

Not only will income return to normal in the year following the consumption boon, but consumption will decrease because the postponed taxation will decrease taxpayer incomes. Companies therefore scale back production in anticipation of lower future demand and the administrative cost associated with the irregular stipend payments also increase the tax burden. Irresponsible spending today causes a tax hike tomorrow, and any increase in the future tax burden will discourage investment. As a result, productivity declines and growth slows.

Repeatedly adopting irresponsible policies of praying for a miracle will only lead to long-term stagnation. Every policy that does not lead to growth increases the burden on future generations, making the fate of government debt more uncertain. The role of policy should be to reduce uncertainty and create an environment in which people can invest and consume with confidence, but in Japan, policies themselves produce uncertainties.

Is the current situation unavoidable because of the aging population? While Japan’s average life expectancy has increased by 20 years since the start of the national pension system in 1960, the starting age for pension benefits remains 65 years of age. The increase in life expectancy has been supported by improved health and the current labor force participation rate for the 65-69 age bracket exceeds 50%. On the other hand, social insurance premiums account for about 30% of income. The problem may not be the aging per se, but the fact that the national pension system has not kept pace with the speed of societal change.

The only way to achieve sustainable economic growth is to increase the productivity of workers and companies, thereby raising lifetime income and production. Growth will not continue if the government forces companies to raise wages. Instead, the government should remove barriers to work motivation and income growth while terminating unfocused benefits and ill-conceived policies.

It is impossible for the government to predict growth sectors or future unicorn companies with certainty. It should raise the skills of the entire population through investment in human capital and encourage people and companies to find sources of growth on their own. We need an environment that respects diversity, encourages an entrepreneurial spirit and embraces failure, instead of being guided by rules of thumb based on outdated values and practices.

This applies not only to government policies, but also to education and research environments, including companies and universities. There can be no sustainable growth without an environment in which diverse personal skills and production technologies can grow freely.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

January 9, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun