The Kishida administration has come up with “unprecedented” measures to counter the declining birth rate, vowing to double the budget for children and enhance child-rearing policies.

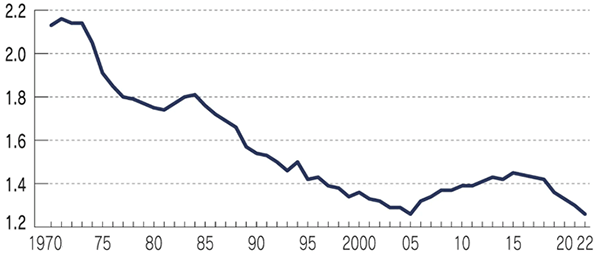

For half a century, the total fertility rate (TFR) has remained well below the level required to maintain the population (replacement level) (see Figure 1). As the TFR decline is a common phenomenon in developed countries, many countries are looking for effective policies to address the decline. Are the goals for the unprecedented measures realistic under such circumstances? Can these measures be expected to be effective commensurate with their costs? Will any TFR rebound achieved through bold policies be sustainable?

In this article, I would like to examine the declining TFR from a medium- to long-term macroeconomic perspective, focusing on changes in the family environment as the core for childbirth decision making.

◆◆◆

If economic growth increases income, people will have access to more goods and services, and be able to increase the number of children they have. However, raising a child takes both money and time. If wages rise, the opportunity costs lost due to childbirth and childcare will increase in a manner which discourages women from having and raising children.

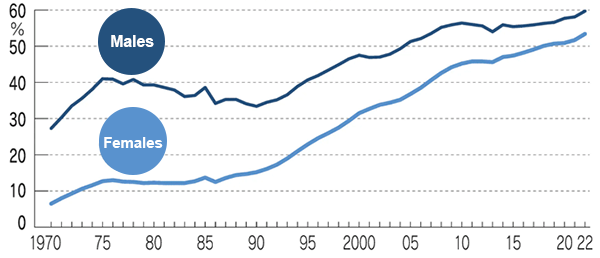

In 1970, 27% of men and 7% of women went on to college. Today, however, more than 50% of men and women do so (see Figure 2). At the same time, the cost of sending children to college is rising faster than incomes. The average time and cost that parents devote to children from their birth until they start working are also increasing. The distribution of time use among married households shows that time spent on raising each child has continued to increase.

What are the factors behind these changes? It is necessary to take into account not only macroeconomic growth, but also the evolution of the wage system in response to changes in the industrial structure and the skills required for workers. If demand for high-skilled workers who can make full use of artificial intelligence technology increases along with their wages, parents may also want their children to learn such technology. It is not difficult to imagine that if wage gaps widen due to a decline in wages for low-skilled workers, enthusiasm for education will be amplified.

While the supply of high-skilled labor is desirable, if the time and money to be spent on educating a child increase, people may be tempted to invest their limited resources in fewer children rather than having more children. If they do not think they can afford to make sufficient educational investments, they may choose not to have a child.

In Japan, mothers have typically been the main contributors to domestic work and child-rearing. In considering fertility trends, it is important to understand what women spend their disposable time on and how women's wages have evolved, which represents an opportunity cost of domestic labor. In the past half century, the increase in educational levels of women has been accompanied by the structural expansion of the service industry where it is easier for women to demonstrate their prowess. In addition, the demand for labor in areas such as nursing and medical care, where women have a strong presence, has increased in line with the aging of the population. This trend has only highlighted the opportunity costs of childcare.

Technological innovation has contributed not only to production activities in the market but also to improving the productivity of domestic services in the home. The biggest change in the allocation of time for married women since the 1970s has been the decrease in time spent on housework. The increased availability of inexpensive home appliances has contributed to women's disposable time significantly.

◆◆◆

In a joint study with Kanato Nakakuni of the University of Tokyo, we analyzed the impact of technological progress on family formation and women's time allocation using various data including wage and employment data in Japan from 1970 to 2020. Not all workers benefit from technological progress in the same way. We divided the effects of technological progress into three components: general productivity growth that raises wages for the entire workforce, skill-biased technological change that influence wages for high-skilled workers, and progress that enhances women's productivity relatively more than that of men.

We found that technological progress leading to overall wage increases has had the effect of reducing women's work and increasing their leisure time through income effects. In addition, skill-biased technological progress encourages parents to invest in educating their children. This is what lies behind the continued increase in educational investments in spite of a hike in the educational costs. Despite the progress in skill-biased technological innovation, the wage gap between education levels in Japan has not widened as much as in other countries such as in the United States. This trend has been remarkable particularly among women’s wages, and a rise in the supply is an important factor to account for the observation.

Our study also showed that changes in productivity, which increase the value of women's labor, lead to a decline in the TFR and marriage rate. This is because the opportunity cost of child-rearing increases along with an increase in women’s earning capacity in a manner which reduces the economic benefits of marriage. The study also confirmed that even if the cost of education decreases and reduces that burden on parents, it would not necessarily boost the TFR, but rather may act as an incentive to reduce the number of children further to provide even fewer children with higher education.

This study suggests that the medium- to long-term TFR trend is influenced by a combination of slowly but steadily changing factors, such as the income level of the economy as a whole, changes in the income structure such as wage disparities between men and women and between education levels due to technological changes, rising education levels, and changes in the composition of the workforce. Do unprecedented measures to combat the declining TFR have the power to reverse these multiple trends, and should we aim to do so?

In Japan, the gender pay gap, though narrowing, is still large. While it is gratifying to see women's income rise, it cannot be ruled out that if the gap continues to narrow without an increase in men's income, it may actually accelerate a decline in the TFR and marriage rate.

The college enrollment rate is expected to continue growing and it is unlikely that the enthusiasm for education will wane, so couples may continue to prioritize increasing investment per child rather than having a larger number of children.

Parenting is a long-term project that can last as long as 20 years. It is difficult to make a decision about childbirth based on policies that undergo frequent changes, such as the abolition of tax breaks for young dependents, the reduction of child allowances, and the loss of eligibility for such allowances. If spending on unprecedented measures to address the declining TFR leads to an increase in the tax burden on future generations, reducing their disposable income, it may exert further downside pressure on the TFR. If couples cannot expect their incomes to grow to support their extended family, it is natural for them to hesitate to have children.

Of course, we do not have children for the sake of national economic revitalization or sustainable public finance. There is great value in building rich human and social relationships through the experience of raising children. It is important to understand what barriers prevent people who want children from having them and consider policies to remove such barriers.

If the problem is the future labor shortages that would negatively affect economic growth and fiscal management, we should not aim to solve such a problem by introducing a series of child support policies that are uncertain to lead to a sustainable increase in the TFR. It would be more effective to remove the policies and barriers that hinder growth, achieve stable employment and income growth, and increase the earning capacity of men and women. If people have the prospect for income levels that will allow them to support families and the ability to return to stable jobs with enough income after leaving work to give birth and raise children, the barriers for women to have children may be lowered.

While the nature of the family is changing amidst large trends of economic growth and structural transformation, it may be counterproductive to continue unprecedented spending measures based on unrealistic goals. It is important to understand the current situation based on medium- to long-term data, identify the barriers facing people of childbearing age, set realistic goals, and take sustainable measures.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

October 26, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun