Microeconomics focuses on individual economic entities such as households and firms, while macroeconomics analyzes the economic dynamics of an entire country, including economic activities of individual entities and their government. This is the understanding that most people likely have.

Although this framework has remained unchanged, a shift occurred in macroeconomics in the 1970s in which explaining the movement of an economy as a whole became based on the behaviors of microeconomic entities. It may seem surprising to some that microeconomics is necessary for macroeconomics, but it is as natural as understanding that the undulations of trees in the wind are the key to understanding the undulations of a forest.

I would like to explain what kind of analysis is progressing currently in macroeconomics, citing specific examples.

Analysis that takes inequality into account

Since the 1990s, rather than utilizing a uniform “representative agent” that does not accurately reflect reality, methods have been developed to analyze the behaviors of people with different attributes such as income and educational background. These methods have made it possible to take disparities into account, explaining why assets concentrate in the top income bracket and who would benefit or lose from tax reform. The scope of research has thus expanded greatly.

Since the 2000s, it has become clear that individual heterogeneity and disparity trends play an important role in assessing macroeconomic phenomena and policy effects.

For example, whether a uniform cash handout within a severe recession can stimulate consumption enough to put the economy on a growth path may depend on the proportion of people who spend it on consumption. If consumption depends on individual attributes such as assets, income, and age, the key to agile and effective policy may be understanding asset and income disparity trends in normal times.

“Family macroeconomics,” which focuses on the economic activities of the family, has also developed significantly in recent years. While family formation and birth analysis have a long history in fields such as demography and sociology, family decision-making affects micro and macro-economic variables, and vice versa.

Marriage, childbirth, and decisions related to child education and higher education can lead to significant fluctuations in family assets and consumption. Childcare and housework affect available work hours, jobs, and career paths, while divorce and bereavement pose income risks. Many people leave their jobs to care for their parents. Changes in family structure and risks facing families affect individual behaviors. Furthermore, on a macroeconomic level, decline in marriage and birth rate leads to a reduction in the workforce, and an increase in the proportion of elderly people leads to significant changes in macroeconomic production, growth, and fiscal conditions.

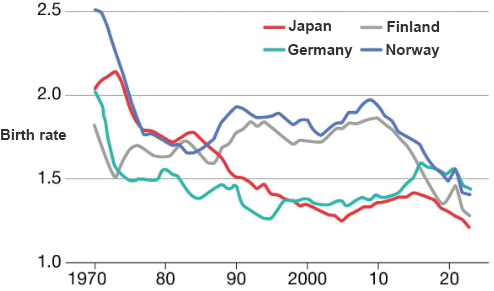

A decline in the birth rate is a challenge faced not only by Japan but also by many other countries. The downward trend in birth rates can be seen even in countries that provide generous child-rearing support or those that boast the world's highest gender balance, where support is provided for work-family balance.

In Japan, where marriage and birth rates have been declining simultaneously, about 30% of men and 20% of women remain unmarried at the age of 50. The most frequently cited reason for hesitation about having children is the high costs of parenting and education. However, the solution is not as simple as encouraging marriage or lowering the cost of education.

The decline in birth rates is not a recent phenomenon; it has been going on for half a century, since the 1970s. This has become a serious problem even in the Nordic countries and Germany, where university education is free. It doesn't seem to be a problem that can be solved by any single measure.

Background for the desire to educate children

Spending on college education, cram schools, and extracurricular activities are the result of family choices. Since the 1970s, household spending on education per child has risen in Japan. However, the idea that subsidizing education will reduce household spending on education and lead to an increase in the number of children is not realistic. Despite women's growing participation in the labor force, rising income levels, and opportunity costs, the time that couples spend on raising their children has increased. What is behind the desire to provide education for children even at such high costs?

University of Pennsylvania Professor Jeremy Greenwood and his colleagues have developed a macroeconomic model that comprehensively explains the decline in marriage and birth rates, increases in educational levels, and changes in time allocation inside and outside the home in the United States from the latter half of the 19th century to 2020. They analyzed how people who became wealthier under changes in wages and the prices of durable goods and relevant technological innovation adjusted their decisions on leisure time, child education, and family size.

In their research, they argue that factors behind declining birth rates and the increase in resources devoted to education per child include skill-biased technological innovation (which requires that workers have appropriate skills) and higher education wage premiums (the tendency for higher education to be linked to higher wages). They also explained that the development of durable goods technologies (e.g., dishwashers and robot vacuum cleaners) contributed to a decrease in household labor time and an increase in leisure time.

Using this model, I analyzed the situation in Japan with Kanato Nakakuni of the University of Tokyo, taking into account the different wage structures for men and women and women’s time allocation preferences. The analysis indicates that the expansion of employment opportunities for women and rising opportunity costs have been the key factors explaining the birth rate decline over the past 50 years.

In South Korea where the birth rate is declining more severely than in Japan, many relevant studies have been conducted. A study by Virgina Commonwealth University Professor Minchul Yum and his colleagues shows that rising educational costs are certainly a major factor behind the declining birth rate. However, the study also shows that in addition to wanting their children to receive a good education to help them earn higher incomes, parents also value their children’s relative positions among their peers, making the educational environment overly competitive. Under preferences based on such “status externalities,” low-income families are more likely to feel a greater educational burden and decide not to have children.

The study argues that imposing a tax on education to raise the cost of education will lead to an increase in the birth rate (although it may have the effect of reducing wages). This argument is similar to the reasoning behind China's policy of banning cram schools.

Measures to address the declining birth rate are cited here to exemplify policy effects. When policy effects are assessed, it is necessary to consider how policies will affect the decision-making of different types of people, what the top priorities are, and the extent to which side effects should be taken into account. State-of-the-art macroeconomic analysis methods provide useful tools for such considerations.

(For reference, see Greenwood, J., N. Guner, and R. Marto (2023). The great transition: Kuznets facts for family-economists. In S. Lundberg and A. Voena (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of the Family. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Kim, S., M. Tertilt, and M. Yum (2024) “Status Externalities in Education and Low Birth Rates in Korea,” American Economic Review, 114(6): 1576–1611. Kitao, S. and K. Nakakuni (2023) “On the Trends of Technology, Family Formation, and Womenʼs Time Allocation,” RIETI Discussion Paper, 23-E-075.)

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

October 12, 2024 Weekly Toyo Keizai