COVID-19 Crisis and Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

The year 2022 has begun. In the past two years, Japan and the rest of the world have remained plagued with the spread of COVID-19.

In September 2021, the Japanese government launched the Digital Agency, reflecting on its failure to pay a 100,000-yen cash stipend to all citizens quickly and smoothly under its first state of emergency declaration amid the initial wave of COVID-19. This represented one of the domains in which the COVID-19 crisis triggered some reform. Regrettably, however, in the past two years the recognition of essential challenges such as population decline and fiscal and social security reform that have existed since before the crisis has weakened among citizens.

This might have been inevitable as indicated by a theory of motivation known as Maslow's hierarchy of needs. According to the theory, people have a pyramid hierarchy of five categories of human needs—physiological needs, safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem needs and self-actualization needs—that they prioritize from bottom to top. Unless lower needs are satisfied, people remain unmotivated to satisfy needs that are higher on the pyramid.

Needs in lower positions of the pyramid are physiological and safety needs. As COVID-19 has threatened the safety of human lives, people have stayed unmotivated to deepen talks on population decline and fiscal and social security reform as medium to long-term challenges.

Furthermore, concern has recently grown globally over the new Omicron COVID-19 variant that was first reported in South Africa. A sixth wave of COVID-19 infections could hit Japan as well. However, the progress in COVID-19 vaccination and drug development apparently signals the end of the pandemic.

Shock of a 12-million-person decline in productive population

The Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications published the final results of Japan's 2020 population census on November 30, 2021. The most shocking item among the results was a rapid decline in the productive population aged between 15 and 64. Population census data indicate that the productive population peaked at about 87.16 million in 1995 and declined to about 75.08 million in 2020. In the 25 years between 1995 and 2020, Japan's productive population decreased by as many as 12 million people.

However, this is nothing more than the beginning of the year 2040 problem. Regarding population, the Japanese economy is actually facing three problems: the year 2025 problem, the year 2040 problem and the year 2054 problem. What are these three problems? As is well known, the year 2025 problem means that baby-boomers will turn 75 by 2025, increasing upside pressure further on healthcare and nursing care expenses. According to Population Projections for Japan (2017, medium-fertility and medium-mortality assumptions) by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the population aged 75 or older will stand at 21.8 million in 2025, accounting for 17.8% of Japan's total population at 122.54 million.

The Year 2040 and Year 2054 problems

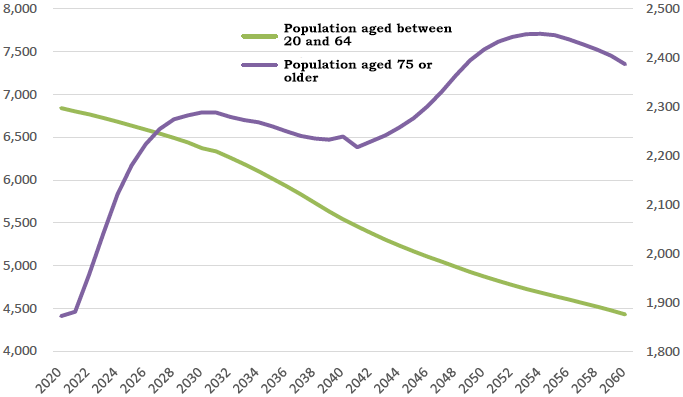

What is the year 2040 problem? This problem is that the working population (aged between 20 and 64) will decrease by as much as 10 million in only 15 years between 2025 and 2040. The above-cited population projections indicate that the working population (aged between 20 and 64) will decrease from 66.34 million in 2025 to 55.42 million in 2040. The annual average decline works out at about 0.73 million, even faster than the average drop of 0.48 million in the productive population between 1995 and 2020. This projection indicates that the Japanese economy could face serious labor shortages unless Japan proactively accepts immigrants.

An even more serious problem is that while the productive population rapidly declines, the population aged 75 or older (though decelerating growth temporarily in the 2030s) will continue increasing until 2054. I call this tentatively the "Year 2054 problem." According to the above-cited population projections, the population aged 75 or older will reach 24.49 million, amounting to about 25% of the total population. This means that one out of every four persons will be aged 75 or older. Japan will thus become an ultra-super-aging society, which will be unprecedented in human history.

How would the fiscal and social security pictures look then? Given the limits on the tax and premium payment capacity of the working population (aged between 20 and 64), the definition of elderly, which is often those aged 65 or older at present could be changed to those aged 75 or older.

At a time when the end of the COVID-19 pandemic is signaled, the time might have come for us to consider how to address the three population problems (the year 2025, 2040 and 2054 problems), including how to reform fiscal and social security systems, on which talks have been stalled under the pandemic.

As the new year 2022 has begun, there are only three years left for addressing the year 2025 problem. It may be too late to address this problem, but this will be followed by the year 2040 and 2054 problems. Serious talks are required on how Japan should address the three problems as a global top runner in population decline and aging.