A six-month, four-day workweek trial was conducted in the UK beginning in June 2022, and more than 90% of participating companies said they would like to continue the four-day workweek after the demonstration experiment ended (BBC news [1]). The reason for the schedule is to improve productivity and work-life balance. Increasing labor productivity is essential if working hours are to be reduced. What is the key to achieving high productivity with shorter working hours? This column introduces a study by Kamei and Tabero (forthcoming [2]), who conducted a laboratory experiment proposing that workplace democracy within an organization is one of the keys to increasing per-work-time production.

Most production activities of business organizations are undertaken in teams. In team production, the moral hazard problem of employees who simply take advantage of their colleagues' contributions has a negative impact on labor productivity. One of the main reasons for this moral hazard is that firms cannot fully observe the work behavior of their employees (Alchian and Demsetz,1972 [3]). It is unrealistic to expect constant monitoring of attention to work. Even if surveillance were to be strengthened, it would do more harm than good by reducing people's intrinsic motivation and worsening the atmosphere and norms in the workplace. Working from home, which began with the COVID-19 pandemic and persisted after the pandemic ended, makes monitoring even more difficult. Concerns about cyberloafing (the act of using the Internet to do something other than work while at work) and other personal use of work time are also growing. After Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare removed the ban on dual employment in 2018, more workers started to work multiple jobs, and some of them may be secretly working side jobs during work hours. Kamei and Tabero (forthcoming) argue that a democratic culture in the workplace increases employees' cooperative attitudes, intrinsic motivation and willingness to work (e.g., Deci and Ryan, 1985[4]), and thus increases hourly labor productivity.

Experimental Environment and Design

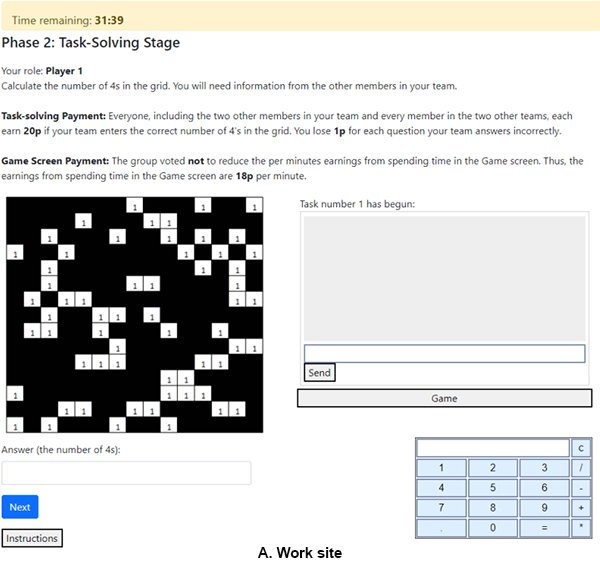

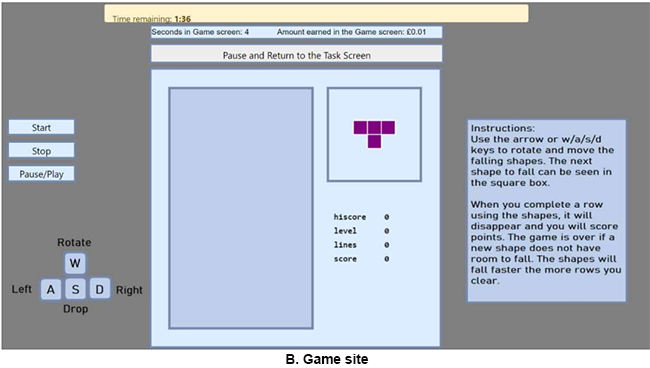

The economic experiment was conducted using university students at the University of York in the UK as subjects. The total number of participants was 552. Subjects in the experiment are assigned to teams of three to work on the collaborative task shown in Panel A of Figure 1. In the collaborative task, each team is given a 15 x 15 table with the numbers 1, 2, 3 or 4 randomly placed in each cell. The team is rewarded for correctly counting the amount of 4s in the entire graph. At the beginning of the experiment, each team member is assigned a number, player 1, 2, or 3, such that they have different numbers from each other. The table that player k (1, 2,or 3 as explained above) receives includes only the ks while the other three numbers are blacked out. Panel A of Figure 1 is an example of Player 1's computer screen. All cells containing numbers other than 1 are blacked out. Each subject counts the number of cells containing his or her number, shares it with the team, and then must correctly calculate the number of 4s based on the combined figures. For example, in a table where numbers 1, 2, and 3 are 32, 14, and 43, respectively, the number of 4s is 225 - 32 - 14 - 43 = 136. Teams can work on collaborative tasks for as long as they like for 35 minutes.

Each team was matched with two other teams, making a group of three teams. This means that each group has nine subjects. This design setup corresponds to the fact that in real business organizations, each section often consists of several work teams. The compensation system was set up as group revenue sharing. When a team completes one collaborative task correctly, each of the nine members of the group earns 20 UK pence (the rule is that the reward of 1.8 UK pounds per correct answer is divided equally among the nine members). Each person's reward depends not only on the work of his own team but also on the work of the other two teams.

A novel feature of this experiment is that each member can secretly change the computer screen to the Tetris game shown in Panel B of Figure 1 during work time. No one, including their teammates, is made aware of a member's gaming activity. This setup is parallel to the real-world examples of modern distractions at work, such as cyberloafing and moonlighting. For every minute spent on the game screen, he/she also receives a monetary reward of 18 UK pence. This models the contribution of private use of work time to increased personal utility. In other words, all the subjects in the experiment had to do was to decide (a) how to allocate the 35 minutes between working and game time, and (b) how hard to work when they decide to work.

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

At the beginning of the task‐solving phase, a policy that reduces the laziness incentive (reward from the game screen) may be introduced for each group. There are two treatments that vary by changing the process to decide whether to enact the policy as follows:

Democratic treatment: Policy implementation is determined by vote. Each team has one vote. The three members of the team discuss the pros and cons of the policy, and then decide if they are for or against the policy. If two or more teams in a group agree, the reward from staying on the game screen will be reduced from 18 UK pence/minute to 16 UK pence/minute.

Non-democratic treatment: Policy implementation is randomly determined by computer. This means that there is a 50% chance that the reward from slack work on the game screen will be reduced to 16 UK pence/minute.

Of the 552 subjects, 279 participated in the democratic treatment and 273 in the non-democratic treatment. The reduction policy (from 18 to 16 pence) can be interpreted as a substitute for increased monitoring and penalties (when negligence is discovered). The probability of uncovering idleness is assumed to be small, and the effect of the reduction policy on lowering the expected material gain from idleness is assumed to be only 2 UK pence/minute. Thus, the reduction policy does not significantly affect the monetary gain structure, but it can explicitly incorporate democratic culture and procedures regarding institutional implementation into the treatment of democratic settings. A comparison of work productivity between the democratic and nondemocratic settings is the objective of this experiment.

Democratic culture contributes to higher per-work-time production

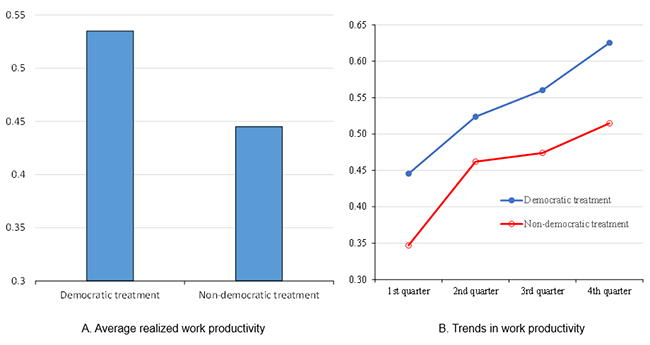

Time and coordination among teammates are both needed to reach the correct answer in a collaborative task. Panel A of Figure 2 shows the number of correct answers per minute of team work (when three people worked on a task for one minute without abandoning the work task) per treatment. The calculations were performed using all data regardless of whether a reduction policy was introduced. The result shows that the number of correct answers per minute of teamwork was 0.535 in the democratic treatment. This productivity value means that if the subjects were to work without playing Tetris for 35 minutes, they would be able to answer 18.7 questions (=0.535 x 35) correctly. On the other hand, the work productivity in the nondemocratic treatment was 0.445, 16.8% lower than in the democratic setting. The per-work-time production in the democratic setting is statistically significantly higher than in the nondemocratic setting (two-sided p < 0.05, bootstrap method).

The effect of democratic culture on work productivity was not affected by the vote outcome (i.e., whether the reduction policy was implemented). When the policy was in place, productivity was 0.529 correct answers/minute in the democratic treatment and 0.462 correct answers/minute in the nondemocratic treatment. When not introduced, productivity was 0.539 correct answers/minute in the democratic treatment and 0.431 correct answers/minute in the nondemocratic treatment. This implies that workplace democracy directly affected worker productivity itself.

In Panel B of Figure 2, we split the data into quarters of the experiment and calculated work productivity in each quarter. We see a persistent positive effect of workplace democracy on productivity. I remark here that workers under democracy decreased work time to some degree, contrary to the positive effect of increased work productivity. This decrease in work time may have been the result of fatigue as a consequence of the hard work. However, benefiting from the strong effect of work productivity (Figure 2), team production (the number of correct answers) was never lower than in the undemocratic setting.

[Click to enlarge]

The results of this study imply that in order to achieve higher labor productivity in shorter working time, it is important to implement workplace democracy with an open atmosphere, for example by implementing decentralization of decision-making authority and successful reflection of employees' opinions into the introduction and change of workplace rules and in the improvement of the working environment. Employee involvement and participation not only strengthen their understanding of group production and moral hazard issues as these necessitate independent thought and deliberation, but also reinforce their intrinsic motivation for cooperation and collaboration. If intrinsic motivation is sufficiently high, they will work autonomously without being monitored or influenced by other external motivators, because of strong employee engagement. Although the situation in Japan, where labor shortages are becoming more and more serious, and the "four-day workweek" argument for reducing working hours per person described at the beginning of this column may seem contradictory at first glance, further promotion of workplace democracy may be effective in achieving both higher labor productivity and a better work-life balance.

Decembet 15, 2023

>> Original text in Japanese