Organizational design addresses various issues that face business entities, such as how to deal with moral hazard problems within organizations, appropriate allocation of tasks, and efficient provision of incentives. In my December 2023 column (Note 1), I discussed the news of a four-day workweek trial in the UK in 2022 involving a large number of companies there and a summary of my own laboratory experimental study, espousing the potential contributions that a democratic culture could have in terms of improving labor productivity in the workplace. When democratic companies make decisions concerning the introduction or change of rules in the workplace and the development of the working environment in ways that reflect the voices of workers, how should the workers’ opinions be collected and how should they be involved in decision-making? In this column, I will present my experiment research jointly with Dr. Tabero (Kamei and Tabero, 2022) (Note 2), which demonstrated that one effective way of accomplishing this is to assign workers in a workplace to small-sized teams as decision-making units within which they deliberate and discuss with each other. This approach is effective because deliberation between team members is likely to generate what is known in behavioral economics as the “truth wins” effect.

The “truth wins” effect, if explained in intuitive terms, refers to the following advantage of a team: a team, which is comprised of multiple members, can make better decisions through communication, discussion, and mutual learning than individuals can when working alone. Deliberation is a process during which team members produce mutual effects, with members modifying their opinions based on other members’ opinions. It goes without saying that as a result of the deliberation process, discussion could lean toward either an efficient or inefficient conclusion (Friedkin and Bullo, 2017) (Note 3). However, when the interests of members are mutually aligned, correct ideas prevail because they are more persuasive. Realizing a communication-friendly and efficient workplace with a high level of productivity means improving the welfare of the great majority of workers and is in the mutual interests of workers.

Economic experiment

We conducted an economic experiment at the University of York in the United Kingdom. The subjects are students there. A total of 408 students participated in the experiment. The experimental approach adopted was to collect behavioral data by conducting a laboratory experiment in which the subjects made decisions in a game simulating transactional situations under settings that are simplified compared with the real-world environment (see Hajimeteno Jikken Keizaigaku [Introduction to Experimental Economics] [2024], a book by KAMEI Kenju) (Note 4). A laboratory experiment can be used to identify causal relationships with high internal validity because a game can be constructed in such a way that it is suitable for verifying theories or hypotheses under analysis.

Two treatments (experimental conditions) were designed. Under one treatment (the individual treatment), each individual acted as a decision-making unit. In this treatment, subjects were randomly assigned to groups of three members and they independently made decisions within their groups. By contrast, In the second treatment (the team treatment), a team of three individuals acted as a decision-making unit. In this treatment, subjects were randomly assigned to groups of nine individuals each. The nine individuals within each group were further randomly divided into three teams of three individuals. Three members in each team were then asked to make single decisions as a team based on deliberation within the team. In short, the difference between these two treatments was whether the decision-making unit was an individual or a three-person team.

Three decision-making units (three individuals in the individual treatment and three teams in the team treatment) played a public goods game. The public goods game is characterized by the conflict between “cooperation” and “non-cooperation.” In this game, each decision-making unit was given an endowment per round and decided how much to contribute to the group to which it belonged. Their contribution benefited every group member equally, such that the sum of gains enjoyed by all members were larger than the contributed amounts (i.e., the investment efficiency was at greater than 1). Thus, the more contributed by every member, the greater the benefit to all members. However, this is a strategic situation in which each member has an incentive to retain their own endowments without contributing, leaving the public goods investment to the other members (allowing for the enjoyment of public goods at no cost).

In a public goods game, if everyone contributes the full endowment amount to their group, the total sum of earnings (total surplus) is maximized in the group. In our experiment, individuals (in the case of the individual treatment) and teams (in the case of the team treatment) voted to establish formal sanction schemes to punish free riders. More specifically, they voted on the sanction rate to the amount not contributed to their group. As a result of the median voting rule, each group could establish either a relatively low sanction rate (representing a non-deterrent scheme), or a relatively high sanction rate (meaning a strict deterrent scheme). In the individual treatment, each individual independently chose a single sanction rate subject to the median voting rule in their group. On the other hand, in the team treatment, three members in each team held deliberations and cast a collective vote as the decision-making unit for the choice they agreed upon. The median of three teams’ votes determined the sanction rate against free-riders for the group.

Experiment results

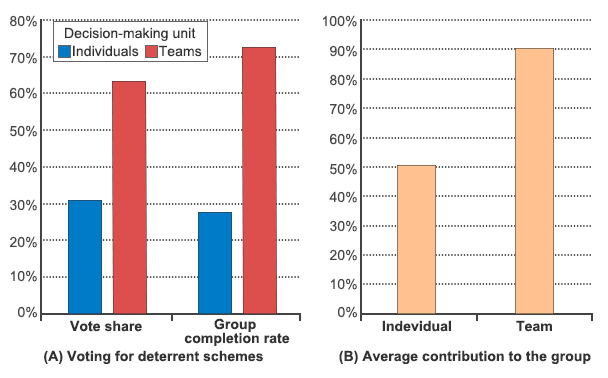

An efficient, deterrent sanction scheme to be implemented within the group eliminates the incentive for free-riding and makes it possible to create an economically efficient situation in which members contribute maximally to each other. However, would people make such efficient choice (i.e., choose a sufficiently high sanction rate)? Panel (A) in Figure 1 shows the percentage of those (individuals and teams) who voted for deterrent sanctions (see “Vote share”) and the percentage of groups in which a deterrent sanction scheme was executed as a vote outcome (see “Execution rate”). Individuals’ views on the sanction schemes were diverse. When they voted independently, only 31% chose the deterrent system. On the other hand, when teams voted collectively after deliberations, more than 60% chose the deterrent sanctions. The large difference between the two treatments in voting behavior is striking.

Success or failure regarding the implementation of an appropriate incentive system had a significant impact on subsequent contribution behavior in the public goods game. Unlike in the individual treatment, teams in the team treatment contributed almost full endowment amounts to their groups (Panel (B) of Figure 1), because of the deterrent sanction scheme developed.

One implication of the findings is that when making decentralized decisions within an organization, it is important to use teams (small groups) to coordinate opinion forming and decision-making, and to allow them to be involved in decision-making by letting them fully debate and deliberate within the teams, so that the “truth wins” effect can be applied to the organization as a whole. This has significant policy implications. For example, the findings support team decision-making as having merit in that it can be used by companies to put into practice a decentralized organization based on small groups, just like the “amoeba management” business administration approach advocated by Inamori Kazuo (the founder of Kyocera Corporation). The effect of collective decision-making based on deliberation within small groups is probably relevant to more than the design of the hierarchy of group members and corporate settings. For example, in the case of implementation of important policies, such as the setting of policy interest rates at Monetary Policy Meetings of the Bank of Japan, multiple-member groups, such as committees, conduct deliberation and make single decisions based on collective decision-making (voting) by members. Although the “truth wins” effect is not all that matters, we can gain some insight if we consider decision-making by an organization from that perspective.

December 17, 2024

>> Original text in Japanese