A social dilemma refers to the situation in which cooperation is beneficial for everyone but the temptation to free ride is so strong that the social optimum cannot be realized if individuals are left to take action based on their own private motivations. Members of our society and organizations such as companies often face social dilemmas. For instance, social dilemmas may occur in situations where people are expected to comply with a code of cooperation or with environmentally-friendly behaviors in society, and in collaboration or teamwork among colleagues when team-based performance evaluations are used at companies. Experimental and behavioral economics studies indicate that people tend to free ride on others’ contributions in a social dilemma (e.g., Ledyard, 1995).

A typical measure used to resolve large-scale social dilemmas in modern society is to change human incentives through institutional formation. For instance, public goods such as the enforcement of law and order, defense, and social infrastructure are provided for through taxation and other rules (including penalties on non-compliance with institutions) to avoid the need to rely on people’s voluntary contributions. Companies devise, design and implement incentive schemes such as performance-based pay and competitive tournaments to keep workers highly motivated. However, can social dilemmas be resolved only through incentive-based reforms?

This column introduces my paper (Kamei, Putterman and Tyran, 2023) that argues that social and organizational dilemma problems cannot be resolved only through institutional formation, and instead proposes that dilemmas can be resolved if we make “2nd-order” social dilemmas which stem from institutional formation sufficiently small.

Institutions and formal rule introduction are not perfect

To allow institutions to work effectively, their manager or operator (often the government) is required to be highly accountable. It is also costly to appropriately monitor people’s compliance or non-compliance with institutions while running them. In a democratic society, civic engagement is effective in imposing accountability on government action and operations. For instance, many citizens devote an hour or so daily to following the news, and also fulfill the civic duty of voting in elections, and some citizens engage much more. However, the effect of one person’s civic engagement is usually extremely small, leading to second-order social dilemmas: one may gain greater economic benefit by free riding on the civic engagement of other people and using more time on activities that provide personal benefit.

At firms, social dilemmas cannot be resolved completely through improvements in contract or pay systems alone. In order to improve labor productivity, firms may improve pay systems and human resources management to reduce moral hazards and the temptation to work slowly. However, monitoring is required, given that workers’ performance is not perfectly observable (Alchian and Demsetz, 1972). In recent years, workplace reforms that include methods of improving employees’ work engagement have been considered in Japan. When employees participate in in-house, bottom-up institutional design at democratic companies, they must naturally be more engaged and should in part undertake the responsibilities involved in the institution, including monitoring (Barron and Gjerde, 1997). This may lead to 2nd-order social dilemmas, however. An employee may attempt to gain a free ride on the monitoring of others that is not directly related to the employee’s own job performance review.

In summary, when society or companies attempt to resolve 1st order dilemmas through incentive changes, the institutional formation may be accompanied by the emergence of 2nd-order dilemmas. How serious can such 2nd-order dilemmas be? How can such 2nd-order dilemmas be resolved?

Experiment environment and design

The experiment was conducted in the Brown University Social Science Experimental Laboratory in the U.S. using university students there as subjects. The subjects were each given initial endowments, were allocated to 24-member experimental societies and then made decisions regarding the 1st-order and 2nd-order dilemmas. Subjects repeated the decisions 15 times to examine the dynamics of civic engagement and cooperation over time. The experiment adopted a mixed economy framework into which a simplified political context was explicitly incorporated. In the first-order problem of providing public goods, non-compliance with taxation was designed to become subject to strong deterrent sanctions in the experiment, while the government collects tax and provides public goods. It was assumed that 40% of the taxpayers’ average income was required for public goods provision that is socially optimal (maximizing total surplus). With the collected financial resources, the government was designed to provide two types of benefits – (a) a direct benefit to all people through provision of public goods such as law and social order, secure and safe social infrastructure, and responses to environmental problems, and (b) an indirect benefit of increasing the productivity of the private sector through educational support for human capital development, the enforcement of rules on implementing contracts, and the like.

On the other hand, it was assumed that the sanctioning institution, such as the government’s monitoring of compliance and punishment of non-compliance, would not work unless people’s civic engagement were sufficient. Under this condition, subjects decided their respective degrees of civic engagement within the experimental society. To keep experimental settings consistent with reality, it was set that civic engagement would be a 2nd-order dilemma accompanying institutional formation that is far smaller than the 1st-order public goods provision dilemma in the mixed economy. In other words, the 1st-order dilemma would be replaced with the 2nd-order dilemma through institutional formation. We asked in the experiment whether people can resolve the resulting 2nd-order dilemma autonomously.

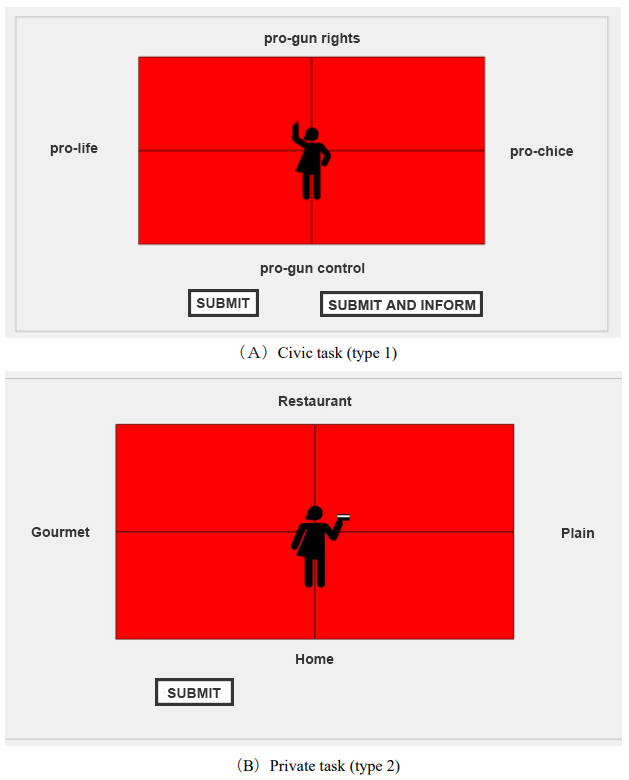

In the experimental society, subjects within the given time decided the degree to which they wanted to perform “civic tasks” and “private tasks” (allocating their pool of resources to the civic or private interest). Completion of a civic task raises the likelihood p that formal sanctioning is in place. Panel A in Figure 1 shows an example of the civic tasks. Task completion entails moving (clicking and dragging) the avatar to the grid that matches a politician’s written policy. Given that the impact of each individual’s civic engagement is small in reality, the probability increase(Δp)was set to be small here. Panel A is the civic task computer screen following the description, “Senate candidate Wendy White favors unrestricted gun ownership and is committed to a woman’s right to choose whether to continue or to terminate a pregnancy.” The quadrant for “pro-gun rights” and “pro-choice” is the correct answer of this civic task question.

Private task completion has no impact on government effectiveness but contributes to increasing personal gains. Subjects are presented with descriptions of consumer selections and then click and drag the avatar to the grids that match the descriptions. For Panel B, an example of the private tasks, subjects move the avatar for the selection between (eating at a) restaurant or home and between gourmet (food) or plain (food) following the description “John Smith eats out frequently at a local diner.” While people decide whether to spend time on private or civic tasks, returns from private tasks can be interpreted as the opportunity cost of civic engagement in this setting.

This study examined civic engagement activities under two scenarios – one with high and one with low gains from choosing the right answers regarding private tasks – to analyze how the size of the opportunity cost influences people’s civic engagement. For both scenarios, gains from solving private tasks were set as greater than the expected returns from solving civic tasks. Thus, in both scenarios, civic engagement represented 2nd-order social dilemmas that are generated to maintain government functions.

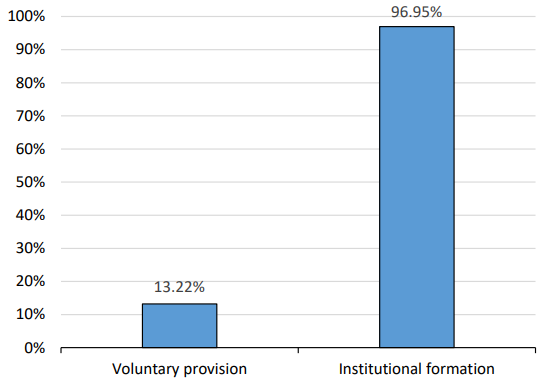

People can resolve 2nd-order dilemmas autonomously when the opportunity cost is low

As explained above, the social optimum was set to be realized when 40% of people’s initial endowments are used for public goods provision. Figure 2 indicates how difficult cooperation is in regard to the 1st-order public goods provision dilemma. It reveals that when subjects were left to make voluntary contribution decisions without institutional formation (sanctions), their contributions were extremely low, indicating sluggish public goods provision. Collected financial resources were limited to about 13.2% of the socially optimal contribution amounts (40% of the endowments). When taxation (including strong sanctions) was enforced, however, most of the subjects complied, allowing financial resources close to the social optimum to be collected. The result in Figure 2 is for the case where the tax institution is highly accountable and efficient.

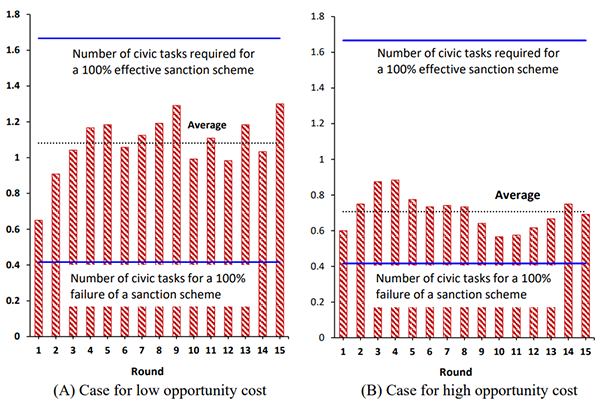

To have an effective institution in place, each subject independently decided how to allocate their time between the civic and private tasks. The time limit in each round was 40 seconds for task-solving. Figure 3 shows the average number of civic task completions per subject. As indicated by Panel A, subjects completed one or more civic tasks on average, in conflict with selfish motivations in the case for low opportunity cost (returns from private tasks), sustaining their prosocial behaviors. The average number was around 52% higher than in the case for high opportunity cost (Panel B). The conclusion is that when the opportunity cost is low enough, people can resolve 2nd-order dilemmas autonomously.

[Click to enlarge]

Leverage effect

If people are left to voluntarily provide public goods, the 1st-order public goods provision dilemma cannot be resolved. If institutional formation is conducted to change incentives, 2nd-order dilemmas accompanying the institution may arise. If the opportunity cost is low enough, however, people can overcome such dilemmas autonomously. Our paper (Kamei, Putterman and Tyran 2023) called the underlying mechanism the “leverage effect,” concluding that the effect emerges because returns gained from the resolution of 1st-order public goods provision dilemmas are far greater than private returns lost due to time consumption on civic engagement to overcome 2nd-order dilemmas. The size of the opportunity cost depends on the tradeoff between private and prosocial behaviors. For example, the opportunity cost will decrease if the government makes civic engagement easier by achieving transparency in its policymaking process and promoting digital transformation to narrow the distance between the government and the people.

This mechanism can be applied to companies that are structurally similar to a civic society. The key point is whether 2nd-order dilemmas arising from contracts and pay systems introduced to resolve moral hazards and other primary dilemmas are easy to resolve. While it is important to appropriately design contracts and pay systems, it is similarly significant to resolve 2nd-order dilemmas. If a team-based pay system including revenue sharing and team performance assessment is used, for instance, peer monitoring and cooperation among colleagues will be required.

It becomes easier to resolve 2nd-order dilemmas if we lower the opportunity cost of prosocial behaviors, or enhance incentives for cooperation, for example, uncoerced intrinsic motivation toward prosocial behaviors. If digital transformation and the positive use of artificial intelligence and other new technologies required particularly for Japanese companies reduce the potential for the generation of 2nd-order dilemmas, for instance, the opportunity cost can be lowered. Employee motivation can be enhanced by the development of flexible work styles that meet the needs of individual employees and democratic workplaces and the improvement of employee engagement, as noted in recent discussions on work style reforms. For Japan, which was ranked as low as 27th among the 38 members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development in terms of labor productivity per hour in 2021, the improvement of labor productivity at companies is an urgent challenge. It may become more important for Japanese companies to enhance workplace efficiency through digital transformation and to reform the Japanese workplace environment to effectively improve internal cooperation dilemmas.

June 21, 2023

>> Original text in Japanese