Introduction

It is known that in Japan, the average wage at foreign-owned firms is higher than that at domestically-owned firms. Even when the characteristics of foreign-owned firms and employees are accounted for, the wage premium of foreign-owned firms over domestically-owned firms that do not engage in international activities such as export or foreign direct investment (FDI) is substantially large, at 21% to 31% (Tanaka, 2022). Why do foreign-owned firms pay much higher wages than domestically-owned firms? One possible reason is that because of factors such as concerns over employment stability, Japanese workers have psychological resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm, and fewer workers are therefore willing to consider that career option. How strong is Japanese workers’ resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm? This article examines this question based on a questionnaire survey conducted by RIETI.

Psychological Resistance to Working at a Foreign-Owned Firm

There are several reasons why Japanese workers are resistant to working at a foreign-owned firm. One is the concern that foreign-owned firms may abruptly close their offices in Japan, resulting in the loss of jobs for its employees. Another is the presence of differences in employment practices between domestic and foreign firms. Large Japanese firms have maintained what is known as the Japanese-style employment system, which is characterized by employment practices, such as “lifetime employment” (working at the same company over a long period of time), “seniority-based wages,” and “company-specific unions” (Kawaguchi, 2017). They are different from Western employment system. Workers who prefer the Japanese-style employment system may be resistant to working at a foreign-owned firm (Note 1).

Outline of the Survey

Under its project “Studies on Foreign Direct Investment and Multinationals: Impediments, Policy Shocks, and Economic Impacts,” RIETI conducts an online survey through a research company. It investigates psychological resistance toward foreign direct investment (FDI) in Japan from June 15-27, 2021, in order to examine the causes of the relatively low level of inward FDI in Japan compared with inward FDI in other countries. Using the survey, we have implemented quantitative analysis. Some of results has already been published in papers such as Ito et al. (2022) and Tanaka et al. (2022).

The above survey also asked the respondents about their opinions regarding working at a foreign-owned firm. This article analyzes and explains those survey results. The survey subjects were men and women aged 18 to 79 from across Japan who were registered with the research company or its partner firms. The survey was designed in such a way that the structure of the survey population is similar, in terms of gender, age and place of residence, to the structures of the entire Japanese population as identified through Japan’s Population Census in 2015. While the total number of respondents in the survey was 4,868, the survey population was narrowed down by age for the purpose of this analysis to a group of 3,377 respondents aged 18 to 60 (the working-age group) because the focus of analysis was the response to the question regarding the willingness to work at a foreign-owned firm.

Survey Results

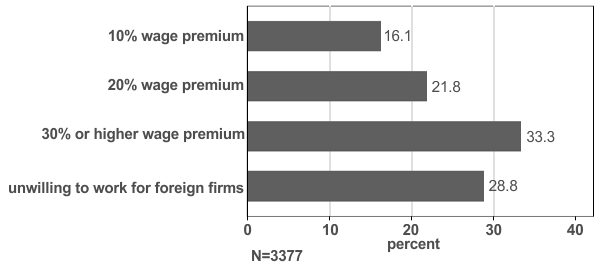

The answers to the following question were used for the analysis in this article: “Please assume that you have been put in a situation where you have to work either for a Japanese firm or a foreign-owned firm as a regular worker. The location of work is Japan in either case. What percent of wage premium (pre-tax) would be necessary for you to consider choosing a foreign-owned firm over a domestically-owned firm?” As shown in Figure 1, 33%, the largest share of the respondents, expressed willingness to work at a foreign-owned firm if they are offered a wage premium of 30% or higher. People who expressed reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the premium accounted for 29% of respondents, the second largest share. The results indicate that more than half of the respondents had a strong resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm.

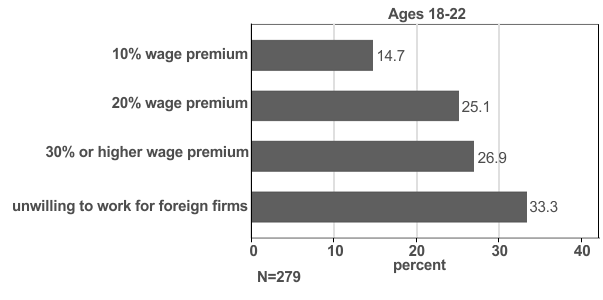

In Japan, recruiting new graduates is more important than hiring mid-career workers. Based on that fact, we additionally narrowed down the survey population to a group of people aged 18 to 22 and tabulated that group’s replies. As shown in Figure 2, in this age group, people who expressed reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the wage premium accounted for the largest share of the respondents, at 33%. Compared with the 18- to 60-year-old cohort that was mentioned earlier, it may be difficult for foreign-owned firm to hire people in this 18-22 age group, who represent the job market for new graduates.

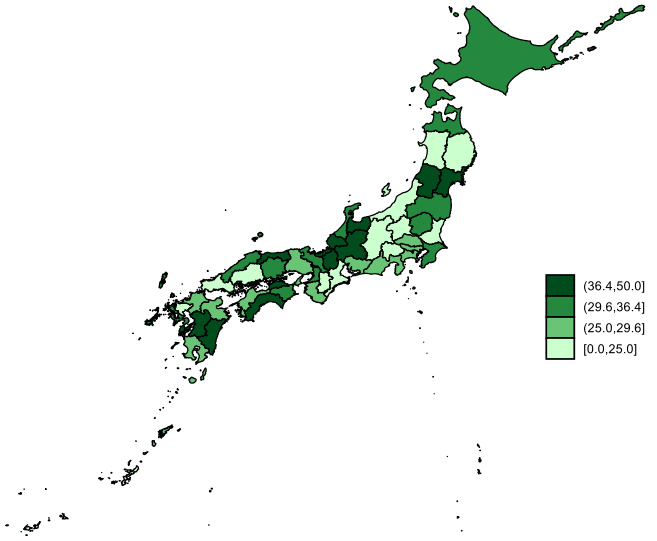

The degree of psychological resistance to foreign acquisitions of Japanese companies varies from region to region (Tanaka et al., 2022). Are there also regional disparities in terms of the degree of resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm? Figure 3 shows that the share of the respondent population of people who expressed a reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the size of the wage premium may differ on a prefecture-by-prefecture basis. In Figure 3, the share of such respondents is higher in prefectures with a darker shade of green. In other words, the resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm was found to be stronger in those prefectures. The resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm was found to be particularly strong in Yamagata, Miyagi, Fukui, Gifu, Shiga, Kagawa, Kumamoto, and Miyazaki Prefectures, as the share of people who expressed a reluctance to working at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the wage premium level in those prefectures was higher than 40%. However, it should be kept in mind that the results were not controlled for the respondents’ attributes such as age, gender, academic achievement, income level, and the number of children. Even when the results controlled for the respondents’ attributes under an ordered logit model, the reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the wage premium level was stronger in Yamagata, Gifu, Kagawa, and Kumamoto Prefectures than in Tokyo.

Estimation Results

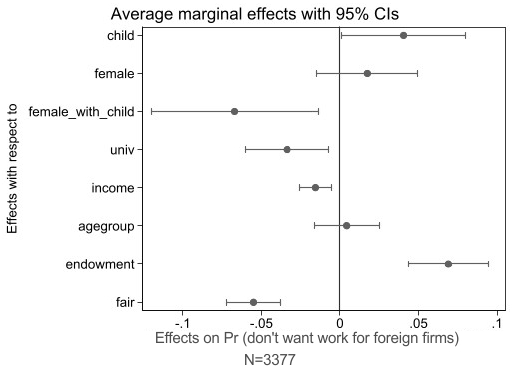

It is difficult for foreign-owned firms to hire workers in the Japanese labor market, where around 30% of the survey respondents expressed a reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the size of the wage premium. What attributes do the respondents who expressed such reluctance have? We estimated the strength of those respondents’ resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm using an ordered logit model with the resistance as a dependent variable and gender, education, income level, presence or absence of children, age, psychological variables such as status quo bias (endowment effect) and reciprocity as well as the prefecture dummies as independent variables.

Figure 4 shows the marginal effects of the respondents’ attributes calculated through the estimation. According to Figure 4, people with status quo bias are statistically significantly more likely—specifically, around 6.9% more likely on average—to express reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the size of the wage premium. On the other hand, people with a university degree are statistically significantly less likely—specifically, around 3.4% less likely—to express such reluctance. The reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm is also relatively low among respondents with higher incomes. As to gender and age, a statistically significant difference cannot be observed between men and women or across age groups at the 5% level. Meanwhile, people with children are 4.1% more likely on average to express reluctance, while women with a child (children) in particular are 6.7% less likely to do so. Women may assume that foreign-owned firms are more sympathetic to childcare needs. These results suggest that exposure to higher education is a more important factor than age. From the estimation results, it can be presumed that resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm arises from at least two major factors, that is, lack of necessary skills in terms of academic achievement and hesitancy rooted in status quo bias. Finally, the respondents who have a strong level of reciprocity as represented by willingness to reciprocate a favor, have little resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm. This suggests that those respondents with high reciprocity have the tendency to avoid discriminating between firms on the basis of nationality.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

This article has made it clear that the Japanese people have strong resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm. The fact that as many as around 30% of the survey respondents expressed reluctance to work at a foreign-owned firm regardless of the size of the wage premium suggests that the labor supply curve for foreign-owned firms in Japan is located leftward of the curve for domestically-owned firms, and that the labor supply for foreign-owned firms is tight. The presence of a strong resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm is consistent with the payment of high wage premiums, ranging from 21% to 31%, by foreign-owned firms. According to the International Direct Investment Statistics of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the amount of inward FDI in Japan on a stock basis is just under 5% of GDP, which is far lower than the OECD average (55%) and is the lowest among the OECD countries. To increase inward FDI in Japan, it is necessary to consider taking steps to reduce the strong resistance to working at foreign-owned firms, for example by making sure that workers employed by foreign-owned firms are not put at a disadvantage in terms of pension benefits.

Acknowledgements

This article owes its findings to the project “Studies on Foreign Direct Investment and Multinationals: Impediments, Policy Shocks, and Economic Impacts.” We offer our heartfelt appreciation for the suggestions that we have received from the participants in the project and the staff members of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry’s Investment Facilitation Division. We also appreciate RIETI staff for translating our article, originally written in Japanese into English.

Supplemental

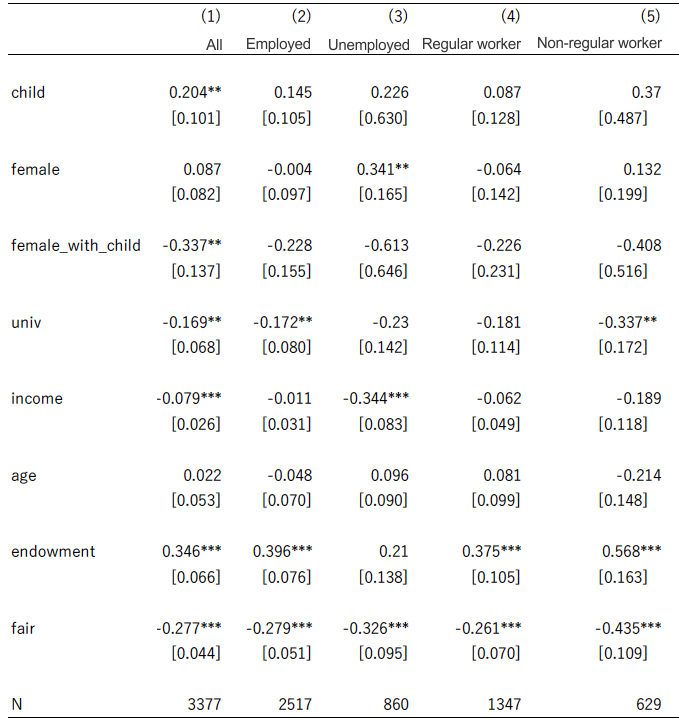

The estimation results obtained through the ordered logit model discussed in this article are as follows:

Dependent variable: The strength of resistance to working at a foreign-owned firm (minimum value:1; maximum value: 4)

The figures in the square brackets represent standard errors.

Note: The definitions of the variables are as follows:

Child: the dummy variable as to whether or not the respondent has children

Female: the female dummy

Female_with_child: the dummy variable that represents a woman with (a) child(ren)

Univ: the dummy variable for having a university degree

Income: the income level category variable

Age group: the age category variable

Endowment: the status quo bias dummy

A higher value is assigned to people with a stronger inclination to reciprocate a favor.