On December 19, 2024, the Bank of Japan released “The Review of Monetary Policy from a Broad Perspective” (hereinafter the “Review”), which evaluates the monetary policy management of the Bank of Japan (BOJ) over the past 25 years. I was given the opportunity to contribute to the Experts’ Commentaries, appended to the end of the Review. In this article, I will make a further argument, focusing on the “behavior and mindset based on the assumption that wages and prices are unlikely to increase,” which is one of the key points of discussion in the Review.

What is most distinctive and commendable about the Review is that the BOJ frankly acknowledges the faults of its past monetary policy. What I found particularly noteworthy is the BOJ’s acknowledgement that its goal of raising the expected inflation rate by influencing expectations through the large-scale quantitative monetary easing had been, from the outset, difficult to achieve in reality. In fact, the Review stipulated that “the changes that large-scale monetary easing brought about in inflation expectations through forward-looking expectations formation alone were not sufficiently effective to anchor inflation at two percent.”

◆◆◆

Why, then, did the BOJ’s monetary policy turn out to be less effective than had been expected? The Review attributed this to the difficulty of changing the “behavior and mindset based on the assumption that wages and prices are unlikely to increase” (hereinafter referred to as “the norm”).

As a factor behind the difficulty of changing the norm, the BOJ cited that “adaptive expectations formation has had a larger impact on inflation expectations in Japan, and such expectations are also strongly influenced by experience.” The adaptive expectations hypothesis argues that people use past experience to predict future outcomes. The Report cites a comparison of the expected rate of price increases in Japan with those of other major economies and finds that Japan has a stronger tendency toward adaptive expectations.

Since the 1970s, macroeconomics has been dominated by a school of thinking based on the rational expectations formation theory (which argues that people make decisions based on all the information they currently have available) has become dominant in the field of macroeconomics. Its development effectively relegated the adaptive expectation hypothesis to the dustbin of history.

One critical implication of rational expectation formation theory is that governments and central banks must anticipate the predictions and behavior of economic agents and implement policies accordingly because the economic agents act based on their predictions of which policies may be implemented. If governments try to implement discretionary or opportunistic policies, private-sector agents anticipate the policy moves and respond, and as a result, the policy effects become weaker than without that response.

Therefore, the question will be whether to implement a policy surprise or rather to limit the latitude of policymaking authorities and the extent to which they can commit to a particular policy. However, because of an excessive dependence on the conventional wisdom of macroeconomics that is premised on rational expectation formation, the policymaking authorities have fallen prey to the delusion that they can change the expectations of economic agents as long as they are committed to following through until the reach their end goal.

The Review considers the “norm” within the framework of the conventional macroeconomic idea of expectation formation, but it is necessary to reconsider the issue from microeconomics and game-theoretic perspectives. For my part, I believe that the comparative institutional analysis (CIA) approach is particularly useful.

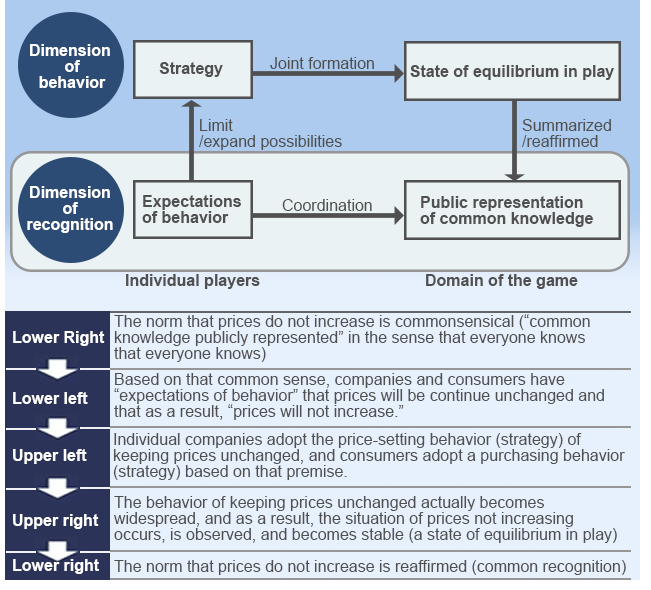

Under this approach, the “norm,” like customs and social norms, constitutes a state of (Nash) equilibrium in an institution under CIA—that is, an equilibrium in a game under game theory. (i.e., the approach regards the “norm” as a stable pattern of behavior resulting from strategic actions taken by players in accordance with the rules of the game). Under the CIA approach, Japan is considered to be in a state of equilibrium of prices and wages not increasing that has been arrived at as a result of the combination of strategic actions taken by various economic agents.

For example, regarding wages, in the “game” between labor and management, an equilibrium in which maintaining employment is prioritized over raising base salaries has continued since the beginning of this century. In the “game” of price setting between companies, we may assume that the economy has fallen into a vicious circle of cost-cutting competition leading to price-cutting competition.

In this case, the realization of those states of equilibrium generates common expectations that prices will not increase, which further reinforces the equilibrium, repeating the cycle (see the figure below). Individual economic agents are not making strategic decisions based on the information available but are taking actions on the premise that the equilibrium that existed until yesterday is still in place today. That behavior is rational in the sense that economic agents are saving resources related to the cost of acquiring and processing information. Adaptive expectations formation not only has a theoretical basis as indicated above, but is a natural process of expectation formation used in the real world.

(when the development of the norm is viewed as a result of a common awareness of patterns of play)

The Review pointed out that “firms have shifted more toward raising wages and prices than in the past, which suggests a change in the behavior and mindset based on the assumption that wages and prices are difficult to raise.” Under the CIA framework, for the equilibrium to change, the rational basis of the strategies chosen by individual economic agents with respect to price- and wage-setting, which constitute the assumptions of the game, must change in accordance with changes in the surrounding environment.

However, although the “norm” appears to have changed, the reality may be merely that economic agents have changed their price- and wage-setting behavior in response to the rising inflation, which is attributable in large part to exogenous shocks. There are no clear signs of structural changes in the competitive environment or corporate behavior in the labor and final market, which are the basis for the formation of the “norm.”

The more the Review emphasizes the strength of the role of adaptive expectation formation in expected inflation, which is a phenomenon unique to Japan, the more doubtful it becomes that the 2% goal was appropriate. In contrast, as evidence of the appropriateness of the price growth target level of 2%, the Review noted that many major advanced economies have set their inflation targets at 2%. However, given the prolonged duration of Japan’s abnormal economic situation compared to the United States and Europe, the 2% goal would have been too ambitious for Japan from the outset. A target of 1% inflation would have been more appropriate.

As in Japan, in other major countries where national elections were held in 2024, the ruling parties lost seats across the board. This is clear evidence that following the prolonged period of global disinflation, inflation has caused greater suffering to the people than the policymakers anticipated. Even so, the BOJ, which determined that price hikes had not yet stabilized, appears to have switched its policy goal from price stability to wage growth to avoid public outrage. It is rare for a central bank to become so obsessed with the state of labor-management wage negotiations as the BOJ has been.

◆◆◆

What the policymaking authorities, including the government, really want to do is to achieve the price stability goal while keeping the pace of wage growth higher than the inflation rate. In other words, the goal is to achieve wage growth in real terms.

Real wage growth can only be achieved through productivity growth, assuming that the labor share and the terms of trade remain constant, both on a firm basis and a nationwide basis. However, productivity growth is outside the scope of monetary policy control. If both the potential growth rate and the natural rate of interest decline to extremely low levels, it is inevitable for the freedom of monetary policy to be severely constrained. It may be said that the private sector has seen through the fog to this reality.

Nevertheless, the government and the BOJ made the mistake of overestimating their influence and importance in terms of being able to manipulate private-sector expectations and of setting a price stability target that was disproportionate to Japan’s true capabilities at the start of the unconventional monetary easing.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

January 14, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun