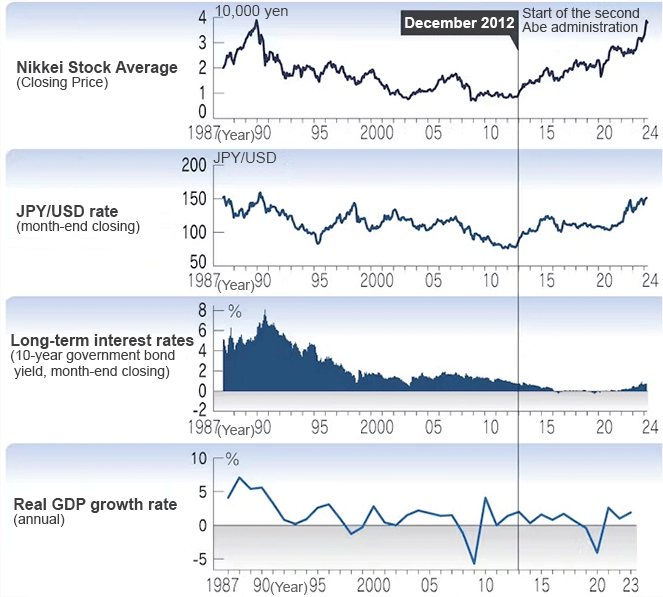

Several economic news stories in the past few months have symbolized a turning point for Japan's macroeconomy. They include the Nikkei Stock Average surpassing its past record high reached in the asset bubble period, the Bank of Japan's revision of its unprecedented monetary easing policy and the yen's decline to the lowest level in 34 years. These developments apparently indicate that the Japanese economy has finally got out of a long tunnel called the “lost three decades.”

In order to consider the future of the economy, however, we must reassess the fundamental macroeconomic policy framework since the second Abe administration.

The framework is usually understood as “Abenomics,” which consists of three arrows: monetary policy, fiscal policy, and growth strategy. However, I believe that the framework should be interpreted as a “stock price targeting policy” and I am prepared for any potential criticism.

Of course, stock prices are an indicator of individual companies and typically, a country’s economic growth rate is the indicator that the country’s government should focus on. While stock prices have been rising steadily since the beginning of 2013, there is no evidence that real economic growth has accelerated since then. Thus, in the end, it is reasonable to say that the three administrations since the Abe government have successfully implemented a “stock price targeting policy”, whether they have been aware of the nature of their policy or not.

Monetary policy is a key tool in implementing a stock price targeting policy. Usually, the theoretical value of a stock price is considered to be the sum of the dividends that may be obtained in the future discounted by present value. As a matter of course, 10,000 yen one year from now will be less valuable than 10,000 yen today, so it should be discounted.

The discount rate that is usually used is the interest rate on safe assets. In that case, the theoretical stock price can simply be expressed as the dividend divided by the interest rate, under the assumption that the dividend will remain constant in the future. If the dividend is a constant percentage of earnings, it is safe to assume that the stock price is proportional to earnings.

The fact that the interest rate is the denominator is significant here. When interest rates are lower, stock prices are higher. However, this relationship is not linear. The closer the interest rate comes to zero, the greater the impact of the interest rate change on stock prices. If the interest rate falls from 0.2% to 0.1%, for instance, the theoretical stock price could double, despite a drop of only 0.1 percentage point. It can be said that the situation in which even the long-term interest rates have remained close to zero due to the prolonged unprecedented monetary easing policy has had a greater positive effect on stock prices than on the real economy.

◆◆◆

The second major role of the unprecedented monetary easing has been the yen’s depreciation. The Japanese economy has frequently experienced appreciation of the yen, forcing the industrial sector to suffer greatly and make adjustments. However, any overt policy of depreciating the yen has not been carried out because it is usually regarded as a “beggar-thy-neighbor” policy.

During periods of yen depreciation, lowering prices of Japanese products in export destination countries to expand export volume reduces demand for domestic products in those countries. Until the 1980s, this export drive was criticized internationally and triggered trade frictions.

In recent years, however, Japanese companies have refrained from lowering prices of their products in foreign countries even under the weak yen and kept their export volumes unchanged, leading to a trend in which the weakening yen pushes up their earnings through increases in yen-denominated prices of their exports. Since theoretical stock prices are proportional to earnings, the weakening yen pushes up stock prices, especially for large export-oriented companies.

The problem is that import prices in Japan are rising due to the yen’s depreciation. Import prices tend to increase directly under the yen’s depreciation mainly for crude oil and grains that are homogenous and non-substitutable. Changes in the global situation, such as Russia's invasion of Ukraine, have exacerbated the effects of the yen’s depreciation, impacting prices of everyday goods. However, price hikes may be more moderate for goods that are differentiated and substitutable, as demand shifts to cheaper goods.

In this way, the unprecedented monetary easing seems to have contributed significantly to the "stock price targeting policy” and given the administration a free hand in fiscal policy.

While fiscal discipline has been mostly eradicated due to enormous spending during the COVID-19 period, the unprecedented monetary easing has helped suppress interest payments on the massive government debt. In principle, the Bank of Japan is prohibited from directly underwriting government bonds, but its commitment to buying abundant long-term government bonds from private financial institutions has made the lack of fiscal discipline undeniable.

With the "stock price targeting policy" based on monetary policy and a free hand in fiscal policy, Japan is truly a fantasyland for macroeconomic policy. Unsustainable macroeconomic policy has been implemented in an isolated environment, leaving Japan far behind movements in the global economy.

It may not be easy for the current administration to abandon the comfort of this fantasy; however, if the inflation target of 2% is too high for Japan's economy, this fantasy might continue for longer than anticipated.

◆◆◆

There are several undeniable problems that cannot be overlooked. The first is the prevalence of a shared expectation that the lax fiscal policy can be continued indefinitely, leading to problems known as fiscal bubbles.

First, in Japan where the government's outstanding debt is 2.5 times the gross domestic product (GDP), a ration that is more than double that of other developed countries, it is difficult to question the sustainability of public finances simply because interest rates have long been well below the nominal GDP growth rate.

If this relationship were to reverse or normalize, the fiscal bubble would eventually come to an end.

Second is Japan’s current trend towards becoming a developing country. With ultra-stable prices and a weak yen, Japan's price levels are unusually low by international standards.

According to the Big Mac indexes (a comparison of McDonald's Big Mac prices in various countries) released by the British Economist magazine, Japan ranked 45th among 55 countries in terms of dollar prices as of January 2024. In the United States, the price was $5.69 (841 yen at the exchange rate as of January), almost two times as high as the actual price of 450 yen in Japan. Most of the countries that ranked close to Japan were developing countries.

If the current exchange rate is an accurate representation of Japan's economic strength, then unquestionably, Japan could be considered a developing country. While the exchange rate level’s contribution to robust demand for inbound tourism is positive for the Japanese economy, it has also led to new social issues as more Japanese workers seek positions in foreign countries under the yen’s weakness.

My subjective impression is that Abenomics was a thorough rejection of the logic and common sense of elite government bureaucrats and Bank of Japan officials. It may have been seen as a kind of paternalism in which policymakers believed that they can improve the economy despite resistance.

The time has come for Japan to face up to the economic impacts of the repeated slogan “things that seem impossible are indeed possible.” This period is a time when technocrats, who were often sidelined, may regain some pride by defending their last stronghold.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

May 8, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun