One of the buzzwords that is attracting the attention of company officials in charge of personnel and labor affairs management is human capital management. “Human capital” refers to workers’ capabilities and skills conceptualized as a sort of business resources. Under this concept, human capital, just like physical capital such as machinery and factories, grows and delivers a return in response to investment.

Under classic frameworks of economics, labor is measured on a flow basis, that is, in terms of man-hours (working hours multiplied by the number of workers per unit of time). Under the human capital concept, workers’ capabilities and skills contribute to companies’ creation of added value as an input of labor on a stock basis.

Human capital is in no way a new concept, as it was first proposed in the field of economics more than half a century ago. Why is it that human capital is attracting attention at this moment? It is because intangible assets, including human assets (human capital), have been becoming more important than physical assets as an input for companies to create added value.

Given that human capital is growing in importance, companies should actively invest in people in order to enhance employees’ capabilities and skills. However, it must be remembered that there are other means to improve employees’ performance. One such means is raising the operating rate of human capital.

It is common sense that in the case of physical assets such as factories and machinery, raising the operating rate, as well as improving their functions, is an effective means of improving performance. This also applies to human capital. Even if the level of capabilities and skills remain constant, it should be possible to improve employees’ performance by raising their operating rate.

◆◆◆

What is the main factor that influences the operating rate of human capital? In my view, it is the employees’ well-being (the state of being in good condition physically, mentally and socially). For example, workers, however capable and skillful they may be, would be unable to perform well if their physical health, a component of their well-being, is compromised.

Regarding human capital, in addition to improving employees’ capabilities and skills through investment in people, raising the operating rate by improving employees’ well-being is an option. Of course, which approach is a better option may depend on the circumstances at the time, but how quickly benefits can be gained is an important issue.

In the case of physical capital, for example, it is obvious that raising the operating rate of existing facilities can both be accomplished and provide benefits in a shorter period of time than introducing upgraded facilities. As the same principle applies to human capital, improving employees’ well-being should be regarded as the centerpiece of human capital management in that doing so achieves results more quickly than investing in new human resources.

Another important point of the argument regarding the expansion of human capital is the strength of the link between investment and workers targeted by the investment. The effectiveness of human capital investment depends significantly on whether necessary investment is targeted at necessary workers, given that the capabilities and skills that need to be cultivated differ from worker to worker.

Amid the rapid advance of technological innovations such as digitalization and artificial intelligence, “reskilling,” which refers to acquiring new skills, is attracting attention. However, there has been little discussion on specifics such as what kind of skills should be acquired by what kind of worker. Nor is there much clarity over the meaning of “DX (digital transformation) professionals,” a term that is often mentioned in the same context as reskilling.

Naturally, both for office workers and blue-collar workers, getting work done digitally without paper—by making full use of such PC application software as spreadsheets, word processors, email, and presentation software—is an indispensable skill for the modern workplace, just as “reading, writing and arithmetic” used to be an essential skillset for the traditional workplace in the past.

It is not an exaggeration to say that using digital devices and applications has now become the set of basic necessary skills that everyone must acquire in order to thoroughly promote digitalization. In that sense, a reskilling initiative to upgrade the skill level of the entire labor force is indispensable.

However, it should be kept in mind that ensuring that everyone acquires programing skills or thoughtlessly increasing the number of data scientists will not necessarily deliver successful results. A DX/AI professional in the true sense of the term means a worker who can figure out ways of changing work processes and ways of doing business with a creative mind by taking advantage of digital- or AI-related personal resources, including skills, knowledge, and experience, rather than a worker who merely possesses such resources.

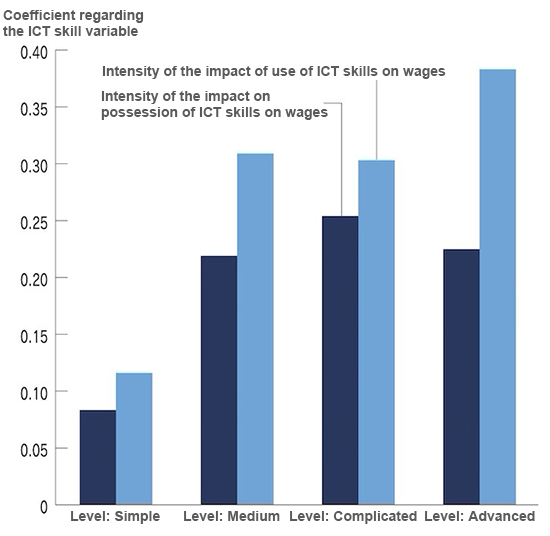

Agreement between the worker and the job assigned is also important. A group that included Professor Shinpei Sano and myself, in a paper published in 2022, examined the relationship between workers’ wages and the level of their ICT (information and communications technology) skills as assessed on a five-grade scale, from “no skill” to “advanced level.”

It is not necessarily true that the higher the level of ICT skills, the higher the wage level. However, we found that the more advanced the ICT skills usage is, the higher the wage level is (see the chart below). In short, merely possessing a high level of ICT skills may bring no benefit to the worker in some cases. Only when the worker engages in a job in which those skills are fully exercised is the skill level reflected in the wage level.

From the above, we can see that rather than merely aiming to raise workers’ skill levels, assigning them to positions—whether within the company or outside—where their capabilities and skills can be exercised brings benefits to both employers and employees.

◆◆◆

Arguments over employee capabilities and skills ultimately lead to discussion on differences between the membership-type employment arrangement, which is unique to Japan, and the job-type employment arrangement, which is prevalent in the United States and Europe. In the case of the job-type employment arrangement, as the capabilities and skills required for specific jobs and posts are contractually specified, workers who meet the requirements are hired to perform the jobs and serve in those posts. As a result, the skills possessed by the hired workers should be the same as the skills used in their jobs in principle.

On the other hand, in the case of the Japanese-style membership employment arrangement, if workers are assigned to jobs in which their skills cannot be fully exercised under a regular job rotation system, there is a lack of agreement between the skills that workers possess and the skills that are required for the position.

If companies aim to enhance employees’ capabilities and skills with a view to human capital management, shifting from the membership-type employment arrangement to the job-type employment arrangement should inevitably be the overarching prerequisite. Of course, I am not suggesting that the job-type employment arrangement should be adopted merely as a matter of formality—doing little more than setting out job specifications—as has become popular recently.

The job-type employment arrangement that I am prescribing here entails that job duties are specified under an employment contract, and hiring and posting are done through public solicitation in principle. Without this job-type employment arrangement, it will be difficult to promote workforce diversity and professionalism, career autonomy, and employees’ engagement in side businesses or multiple jobs, all of which are often cited as important elements of human capital management. Companies hoping to implement human capital management should start by squarely facing up to the challenge of instituting the job-type employment arrangement in the true sense of the term.

* Translated by RIETI.

January 12, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun