The House of Councillors election this July marked a milestone for the administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida because the administration now enjoys the prospect of “three golden years,” a period during which no national elections are expected (barring a snap general election to the House of Representatives) and as a result, it can concentrate on developing economic policies that are truly essential to the Japanese economy, rather than populist policies. I will provide an overview of ideological changes related to recent economic policies observed among mainstream economists and at international organizations, which will be useful for policymaking.

Economic policies can be broadly divided into macro policies, which are mainly fiscal and monetary policies intended to level out and stabilize economic cycles, and microeconomic policies, which aim for income redistribution and efficient improvement of resource allocation. Micro policies encompass a broad range of areas, including tax and social security, competition, innovation, trade, industry, and employment. In particular, policies that are intended to enhance national growth potential through efficient improvement of resource allocation by addressing economic structures tend to be known as structural reform initiatives or growth strategies.

[Click to enlarge]

Compared with macro policies, micro policies are more prone to the influence of political ideology. Looking at the situations overseas, we see that conservative forces place emphasis on market principles and aim to minimize neo-liberal-based government involvement on the regulatory and fiscal fronts. On the other hand, progressive forces place greater emphasis on income redistribution and justify active government involvement, that is, “big government.”

◆◆◆

Naturally, it is important to keep in mind that whereas a shift towards a welfare state system proceeded under conservative governments in the United States and the United Kingdom in the 1970s, neo-liberal reforms were carried out under progressive governments in the 1990s and later. Even so, it is an indisputable fact that those two schools of ideology—conservative and progressive ideas—are considered to be mutually exclusive.

In recent years, however, there have been changes in this ideological conflict. For example, in the “Going for Growth” report, which has been published by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) since 2005, and which points out the priorities for member countries’ structural reform initiatives and growth strategies and assesses the progress in reform, indicators of inclusiveness, such as reduction of poverty and inequalities, were introduced in the 2017 edition, and (environmental) “sustainability” was introduced in the 2019 edition, and they have continued to be included as reform priorities.

Initially after the inauguration of the Kishida administration, there appears to have been controversy over whether emphasis should be placed on redistribution or growth within the government and the ruling parties. However, internationally, the perception has taken hold that if societal challenges remain unattended, growth cannot be achieved. Moreover, “inclusiveness” has been gradually becoming a keyword among mainstream economists as well. For example, Professor Dani Rodrik of Harvard University, an eminent expert on development and international economics and others have established a network of economists that are committed to creating “Economics for Inclusive Prosperity” and held discussions and presented proposals regarding economic policies in a post-neo-liberal era.

Among the network’s members are Professor Daron Acemoglu of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other distinguished researchers at the cutting edge of this field. Those researchers’ arguments indicate a strong resolve to apply the results of research in the realm of mainstream economics to actual policymaking processes based on the bitter lesson of market fundamentalism—that is, the startling widening of inequalities, the concentration of power among megacompanies, and the neglect of attention to the environmental crisis which have all resulted from policies with a strong bias toward market fundamentalism.

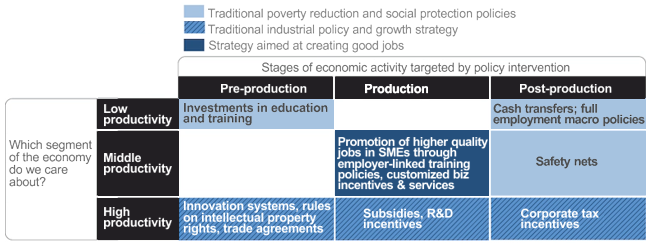

Based on that basic approach, Rodrik, the co-leader of the network, has most recently proposed “productivism” as a new economic policy paradigm that cuts across the political spectrum. Below, I will explain the concept of productivism.

Productivism calls for a broad dissemination of opportunities for productivity improvement, among workers across all regions and all classes. To do so, productivism requires, above all, that governments and local communities, rather than markets, play a significant role.

Moreover, productivism seeks to achieve economic revitalization by placing emphasis on small and medium-sized enterprises over large enterprises, on production and investment over finance, and on revitalizing local communities over globalization. For example, until now, industrial policy has been considered to be inefficient because it is liable to be exploited by interest groups and has usually been rejected on the rationale that “government is not capable of reliably choosing winners.”

On the other hand, Rodrik insists that in most cases, criticism of industrial policy has gone too far given that despite some obvious failures, empirical analyses have shown that industrial policy has worked very successfully when it seeks to promote investment and job creation in economically disadvantaged regions.

As to how productivism should be put into practice, although it may aim for inclusive prosperity, it is not a Keynesian welfare state-type policy that features traditional approaches such as redistribution or social transfer. Promoting supply-side policy action (action on the part of companies)—specifically, providing good jobs to all people—is the core of Rodrik’s proposal.

In order to maintain the middle class, it is important and essential to improve jobs obtained by workers in terms of both quality and quantity even when their level of academic achievement or skills is low, according to Rodrik’s argument. Services industries in particular are a target of this initiative.

The reason why governments should be involved in the creation of good jobs is the presence of externalities. A lack of good jobs in a particular region would results in massive economic, social and political costs. For example, the levels of health and education for the people in the region may deteriorate and crime may increase, and the situation could develop into a crisis of democracy, leading to the escalation of social and political conflicts.

However, companies usually take actions without any regard for such negative externalities. Additionally, in contrast to the above, the creation of good jobs engenders positive externalities, setting off virtuous feedback loops. Nevertheless, companies typically do not support traditional policy measures such as universal subsidies or tax breaks with predetermined quotas as a way to deal with externalities because they feel that it is essential to take into consideration the fact that a great variety and quantity of uncertainties exist and that there is a need to “think and respond to the situation at hand” (contextualization of responses).

In other words, conditions for and approaches to assistance within job creation strategies should be customized according to the peculiarities of the relevant regions and companies and should be flexibly adjusted and corrected in response to changes in the surrounding environment. Therefore, Rodrik argues that the relationship between a government facilitating such adjustments and companies creating jobs must be a collaborative and iterative one, rather than an arms’ length affair. According to his argument, the reason why good-job creation strategies adopted in the past were not necessarily successful is that they failed to evolve due to a lack of customization.

◆◆◆

Another key point of discussion when thinking about strategies that are aimed at creating good jobs is how to approach technology. Rodrik maintains that it is essential to promote “labor-friendly technology,” that is, types of technology that increase jobs, rather than those that replace human workers, and that governments have a role to play in promoting that. With respect to artificial intelligence (AI), he points out the possibility of AI technology contributing to job creation in the fields of education and healthcare.

What implications does the presentation of this new economic policy paradigm have for economic policymaking in Japan? We should recognize that an approach that advocates choosing between reducing inequality and growth, or that looks at these two as trade-offs has already become obsolete. Promoting close collaboration between the government and the private sector, which is indispensable to achieving the two at the same time, is one of Japan’s fortés. There is a Japanese proverb that says, “Those who chase two rabbits will not even catch one,” but “Those who do not chase two rabbits will not even catch one” should be the guiding principle for Japan’s structural reform initiative and growth strategy.

* Translated by RIETI.

September 14, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun