The second stage of Abenomics has kicked in under the catchphrases of "new three arrows" and a "society where all citizens are dynamically engaged." Now that the security bill has been passed into law, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe probably needs to shift the focus of the political spotlight drastically as the original Abenomics policy measures appear to be running out of steam. Still, there is no denying how unanticipated the move was. Despite the presence of various relevant councils of experts, none of them seem to have discussed these key concepts of Abenomics 2.0.

If the intention was to emphasize the "freshness" of the new policy package, Prime Minister Abe surely achieved the intended effect by announcing the package suddenly at a news conference. However, what is becoming increasingly apparent is a problematic aspect of this approach, i.e., the meaning of the key concepts is not necessarily shared widely.

♦ ♦ ♦

Prime Minister Abe specifically cited "600 trillion yen in gross domestic product (GDP)," "fertility rate of 1.8," and "no one forced to quit a job due to caregiving responsibilities" as the new three arrows, but even those closest to him reportedly raised objections to this definition, saying that these are "targets" rather than "arrows."

Meanwhile, in the material provided by the secretariat for the first meeting of the National Council for Promoting the Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens held on October 29, 2015, the new three arrows were redefined as referring to "a robust economy that gives rise to hope," "dream-weaving childcare support," and "social security that provides reassurances." These phrases remind us of "a strong economy," "robust public finances," and "a strong social security system" advocated by the government of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ).

Are there any differences between Abenomics 2.0 and the original Abenomics? It would be natural to consider that the growth strategy, which constitutes one of the original three arrows, has been incorporated into initiatives designed to achieve 600 trillion yen in GDP. However, according to material submitted to the October 15, 2015 meeting of the Industrial Competitiveness Council, "productivity revolution" and the "promotion of local Abenomics" will remain the two pillars of the growth strategy. How will these themes, together with the other two new arrows that are designed to address the problem of low fertility and the need to secure caregiving to the elderly, lead to the creation of a people-active society where each and every person has an active role to play?

The second stage of Abenomics seems to be getting chaotic with the old and new sets of leading players jumbled up.

In order to put an end to this situation, it is necessary to have a cross-cutting theme to bind together the new three arrows and aim them toward the target of creating a people-active society. What is needed here is to reform people-related systems. We must instigate broadly-defined human resources reform, including the improvement of education, and change working styles.

Reforming human resource development practices and working styles is crucial to bringing about innovation and creating a society where people--both men and women alike--can lead a lively working life with a sense of assurance and security, while managing family responsibilities such as childrearing and caregiving to elderly members. Unless such people-related system reform is made the pivot of the overall initiatives toward the creation of a people-active society, the second stage of Abenomics surely deserves to be criticized for being just another set of pre-election pork-barrel programs under the names of childrearing and caregiving support measures.

♦ ♦ ♦

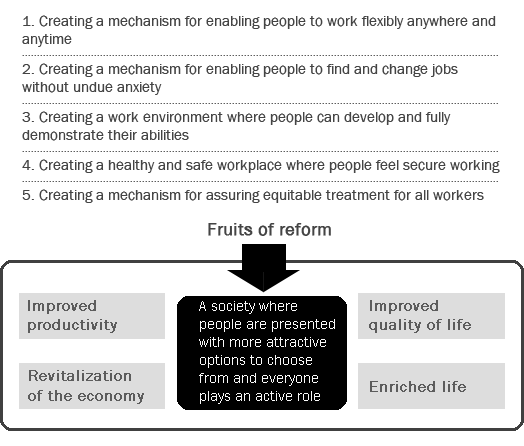

The Regulatory Reform Council, of which I am a member, has put together and released a set of reform measures considered necessary for enabling diverse working styles (see Figure), defining the realization of such diversity as the bedrock of the working style reform. Of the five reform pillars listed, enabling people to work flexibly anywhere and anytime is particularly important in addressing the problem of low fertility and the caregiving needs of elderly people, provided that a healthy work environment and the equitable treatment of employees are secured.

In order for everyone to be able to demonstrate their respective abilities to the fullest extent, it is crucial to enable them to make a satisfactory choice particularly at the gateway to jobs, namely, at the time of obtaining and changing jobs.

The difficulty of reforming human resource development practices and working styles lies in the fact that it cannot be achieved overnight and takes persistent efforts over a long period of time. Even without citing the case of employment system reform in Germany under the government of Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, the next government would probably be the one to reap the fruits of reform undertaken by the current government.

One of the characteristics of the original Abenomics policy is the short-term-oriented nature of the measures implemented. In order to achieve Prime Minister Abe's long-cherished goal of making legislative changes to strengthen Japan's defense and security capabilities, the government needed to accumulate as much political capital as possible by quickly earning scores in the area of the economy. As such, there was no choice but to seek to achieve clearly visible results by focusing on the stock market and the approval rate for the Cabinet.

Under some previous governments, Kasumigaseki bureaucrats were reluctant to introduce policy measures that require long-term commitment, because of the instability of political leadership. Today, however, things are different, and the political leadership is stable enough for them to push through reform by taking a long-term perspective. Despite this, they seem to be in a dilemma, where they cannot help but to pursue even-more shortsighted measures in order to maintain and prolong the current government.

One example of this is the proposed introduction of merit pay for high-level professions, a new remuneration system designed to delink wages for those with highly specialized skills from the number of hours and the time of day in which they work, with the relevant bills slated for deliberation in the forthcoming Diet session. The legislation, if approved, would mark an important step forward in terms of creating a new system of working hours. However, its scope of application is very limited, for instance, to those with annual income of more than 10 million yen, which is problematic in view of the government's goal of creating a people-active society.

Another point I find annoying about the proposed employment system reform is what I call "Dejima-ism," a positive list approach to allowing new things as exceptions while keeping the status quo in the rest, just like the way in which the Tokugawa shogunate government limited contact with the outside world to the tiny manmade island of Dejima while keeping the rest of the country closed under its national seclusion policy during the Edo Period (1603-1868). That is, the proposed regulatory changes would be allowed as an exception and applicable only to a handful of highly specialized high income earners, with no changes made with respect to the remaining overwhelming majority of workers.

Of course, this Dejima-style approach is not without merit. Such an approach would be effective in term of enabling the management to reach agreement with the labor with less friction on the introduction of the new system, and thus, delivering the intended results quickly. However, going forward, it is necessary to secure not only a healthy workplace but also equitable treatment for a broad range of workers wishing to work unconstrained by time, and then to carry the momentum of reform initiatives into the future.

Meanwhile, in order to realize a society where people can choose from diverse working styles, it is imperative to reconfigure the process of policy decision making. Even if various councils put forward concrete policy proposals to reform the employment system, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare would set up a study group to start the policymaking process all over again for the reason that no labor and management representatives are included in the members of those councils. When the study group completes its review of the proposed policy measures, the Labour Policy Council would begin its deliberations on the proposals. Altogether, it usually takes about a year and a half before reaching a final conclusion.

Furthermore, if a related bill fails to pass the Diet in a timely manner, as has been the case with the latest amendments to the agency workers law, it would cause further delays in the process of considering other employment system reform measures.

Working style reform by nature takes time to start delivering its intended effects. It is then all the more important to put it into practice as speedily as possible. To achieve that end, it is necessary to sort out and redefine the roles of the various councils that are currently discussing employment-related matters, and then create a new forum for national debate to integrate them into a single channel. While assuming a tripartite structure to represent the government, employers, and workers, the new forum must be designed in such a way as to ensure that the voices of a diverse group of workers including "non-regular" workers (i.e., part-timers, day laborers, agency workers, etc.) will be heard.

The division of roles must be clear. A major direction and framework for working style reform should be set by a Cabinet-level council composed of the prime minister, other relevant ministers, and experts, whereas the Labour Policy Council, an advisory body to the minister of health, labour and welfare, should consider specific and detailed institutional designs for the work and employment system. In this sense, it is regrettable that labor has no representation on the newly-launched National Council for Promoting the Dynamic Engagement of All Citizens.

♦ ♦ ♦

Working style reform will involve changing the structure, culture, and mindsets to which we have been accustomed for so long. In this context, the "bedrock" that must be drilled into and crushed to pave the way for big changes is our hard heads, rather than existing laws and regulations.

Japan's work and employment system entered a phase of major changes in the 1990s, and we must be prepared for the prospect that it will take a generation before fundamental changes begin to take place. However, new working styles--including those taking advantage of information technology--are steadily emerging in companies headed by young entrepreneurs in their 30s and 40s. It is necessary to implement each step of working style reform steadily and rapidly in the process of continuing to make persistent reform efforts.

* Translated by RIETI.

November 10, 2015 Nihon Keizai Shimbun