Global supply chains are facing the implementation and intimidation of tariff hikes by the second Trump administration. While it is natural to respond to immediate issues, it is also important to steadily pursue long-term measures in anticipation of subtle changes in trends. This column aims to provide an opportunity to consider the challenges surrounding global supply chains, focusing on aspects that are not readily visible.

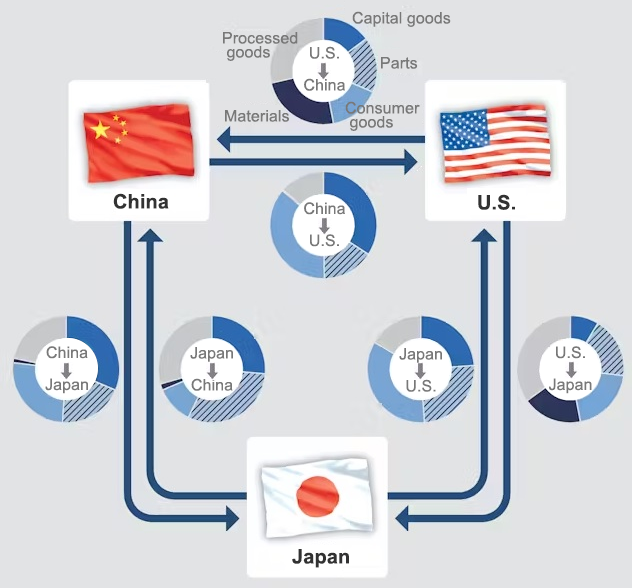

First, as a basis for discussing global supply chains surrounding Japan, let us review the structure of trade between Japan, the United States, and China. It is well known that exports from Japan have shifted to a structure centered on parts and capital goods; however, almost half of exports from China to both Japan and the United States are now also comprised of parts and capital goods (see figure).

Since these goods are highly differentiated for specific uses and are difficult to substitute, it will take a long time to replace them with domestic products even under higher tariffs. Since supply chain restructuring involves costs related to finding, contracting and coordinating with new suppliers, companies faced with tariff policies that are frequently canceled or delayed tend to adopt a wait-and-see attitude.

Increasing reliability and predictability is important for long-term decision-making, and they are incompatible with short-term perspectives that try to opportunistically manipulate transactions by creating uncertainty. In this regard, short-term uncertainty is incompatible with restructuring supply chains.

◆◆◆

In standard theoretical models of international trade, the two key parameters that determine economic welfare are the share of the relevant goods and their elasticity of substitution. The former can be measured at any given point in time, but there is a need to disaggregate it from the industry level to that micro level of individual firms, goods and transactions. In this regard, it is concerning that few companies have a clear picture of their secondary and tertiary suppliers of their own products beyond their primary suppliers.

As for elasticity of substitution, it is necessary to separate technological substitutability from actual economic feasibility of substitution and clarify potential timeframes for such changes to occur. If these economic concepts are linked to recent economic security terms, the share of goods relates to chokepoints and substitution elasticity relates to resilience.

The impacts of tariff hikes should be discussed both in direct and indirect terms. Tariffs inevitably increase the prices of imported goods for consumers, but globalization has made it difficult to see the impact of tariffs due to the increased share of intermediate goods in trade.

Applying the traditional concept of “effective rate of protection” to global supply chains reveals that tariffs imposed on imported intermediate goods can indirectly affect the international competitiveness of exported final goods. Even the limited tariff hikes under the first Trump administration were estimated to have had an impact equivalent to imposing a tax of more than 2% on exports from the United States in 2019. This problem is particularly serious when it involves indispensable intermediate goods such as steel and semiconductors.

It is important not to overlook trade in services and the cross-border transfer of digital data. While trade in goods has stagnated in recent years, trade in services and data flow have continued to expand, which suggests that services and data have replaced goods as the drivers of globalization. Although services and data are less visible than goods passing through customs, the spread of artificial intelligence and other technologies means that global supply chains must now be understood in terms of the flow of services and data in addition to the traditional trade in intermediate goods such as parts and materials.

For this reason, relying on intermediate goods trade data alone makes it difficult to grasp the full picture of the degree of dependence on foreign countries and the international division of labor, especially in advanced economies where the presence of manufacturing has declined. While the protection of personal information requires significant attention, digital protectionism in the form of regulations that restrict the cross-border transfers of data puts a burden on companies that operate globally.

In Japan, detailed analysis of trade in goods using microdata on customs clearance transactions has just begun in earnest. However, services trade data obtained from published balance of payments statistics are coarse in resolution, with coverage of data transfers absent in official statistics. Multifaceted measurement of global supply chains that covers these new aspects is essential.

Another point that is difficult to see but worth observing is a long-term change in global trends. Since the beginning of this century, the world has seen a series of disasters--not only the recent tariff hikes by the Trump administration, but also the global financial crisis, the COVID-19 crisis, and the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As a result of this, global trade, which had been steadily expanding, instead began to shrink or stagnate. In essence, global trade had already reached a historic turning point even before the Trump tariff hikes.

From the era of globalization, when the market economy spread around the world after the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, we have shifted to an era of U.S.-China confrontation. China, which provides a massive low-wage labor force as the “world’s factory,” has failed to implement the reforms promised at the time of its accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) as a non-market economy. Instead, rising wages, preferential treatment for state-owned enterprises, forced technology transfer from foreign companies, and increasing market control and intervention have been emphasized and implemented.

Neglecting these long-term changes due to the distractions provided by the Trump administration’s policy volatility is unwise. The U.S.-Soviet Cold War until the fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent era of globalization each lasted for about 30 years. We should be prepared for the current conflict over the fundamentals of the market economy to continue for a similar period, and are required to develop long-term strategies.

◆◆◆

Although U.S. tariff rates have returned to prewar Great Depression levels, the structure of global trade has already undergone a significant transformation. National economies around the world have become intricately intertwined with each other due to not only intermediate goods trade but also foreign direct investment and production, offshore outsourcing across national borders and corporate boundaries, services trade, and cross-border transfers of digital data. As the operations that are outsourced overseas within supply chains become increasingly sophisticated, countries are required to provide not only low-cost production, but also transparency, predictability, and reliability in their legal and regulatory frameworks.

Therefore, it is necessary to not only address the conspicuous issue of tariffs, but also facilitate international transactions in intermediate goods, which are subject to long-term relationships and the less visible trade in intangible services and data. At a minimum, countries around the world should adapt international rules under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade to the digital age and cooperatively develop the institutional infrastructure that will support market economies; infrastructure that will protect intellectual property, personal information, and property rights and secure the rule of law from a long-term perspective.

In order to prevent the European Union (which has extensive experience in shaping the international order through rule formation) from shifting its focus toward cutting “deals” between large markets, and to ensure that the United States will be able to join our endeavor once the country restores the respect for rules after its current period of protectionist policy due to domestic divisions, it is critical for like-minded market economies, such as the members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), to collaborate closely and strategically with a vision for the future.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

July 17, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun