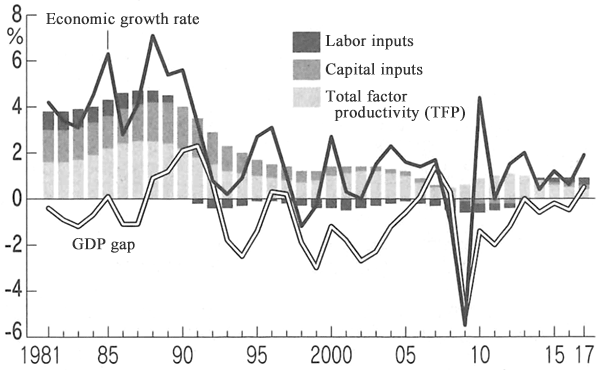

It has been more than six years since the advent of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's second administration in December 2012 ushered in the so-called Abenomics package of economic measures. To begin, let's consider the state of the Japanese economy during that period of time from a long-term perspective (Figure).

The term "GDP gap" refers to the disparity between a country's real GDP and its potential GDP with respect to its economic capacity. In other words, it acts as an indicator that reflects the rate at which a nation utilizes its factors of production. As the figure shows, the GDP gap plummeted well into negative territory amid the economic downturn precipitated by the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in 2008, but subsequently recovered and has been holding to roughly a value of zero since 2013. This would seem to suggest that economic policies implemented under Japan's current government have yielded positive results.

♦ ♦ ♦

On the other hand, Japan's rate of economic growth has been hovering at around the 1% to 2% range during this time. That performance is on par with the nation's average rate of economic growth encountered during the so-called "two lost decades" beginning in the 1990s. Japan’s current government has been championing a series of economic policies geared to lifting Japan out of its low growth rut since the 1990s, yet has failed to deliver successful results with respect to the rate of economic growth. The notion that Japan’s rate of growth remains low even though factors of production are operating at nearly full capacity would seem to suggest that the economy’s lackluster growth is attributable to structural reasons rather than a recessionary, or deflationary, scenario.

The primary factors underpinning Japan’s potential rate of economic growth shown in the figure back up this premise. The potential growth rate can be decomposed into capital input volumes and labor input volumes, and the total factor productivity (TFP) growth rate, which reflects technological progress and other such determinants. First of all, the data indicate that since 2013 Japan’s potential growth rate has been lower than the values prevailing from the 1990s up until the economic downturn precipitated by the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy. Secondly, it suggests that a slowing TFP growth rate is a major factor underpinning this situation.

As such, the notion that TFP growth is slowing constitutes a particularly serious issue with respect to the Japanese economy. The reason being is that economic growth beyond the rate of labor force growth is generally not sustainable in the absence of rising total factor productivity. Even if a labor shortage were to be offset by higher capital inputs, the marginal productivity of capital would decline accordingly.

Moreover, Japan’s labor force is going to decrease as the nation’s population ages. This situation has given rise to mounting concerns in recent years regarding Japan’s productivity. For instance, at the end of 2017 Japan’s Cabinet approved the government’s "New Economic Policy Package" designating the three years from 2018 to 2020 as a period for a productivity revolution and intensive investment, with the aim of making Japan’s economy more productive. Moreover, research papers and informative books on Japanese productivity and technological innovation are being released in increasing numbers.

♦ ♦ ♦

Two key points must be considered with respect to both gaining an understanding of the potential causes of the Japanese economy's stagnating productivity and contemplating measures that could help raise the nation's productivity.

The first key point is the notion that the macro factors underpinning the shift in total factor productivity touched on previously are not limited solely to technological changes in a narrow sense. According to numerous studies from Japan and abroad, changes in total factor productivity also can be brought about by shifting resource allocations among industries, companies, and business establishments.

When it comes to the effects of resource reallocations among industries, for instance, Kyoji Fukao of the Institute of Economic Research (Hitotsubashi University) has reported findings suggesting that resource reallocations among industries in Japan in the 2000s had a substantial negative effect on factor productivity. Moreover, a study on "zombie companies" conducted by Stanford University professor Takeo Hoshi suggests that since the 1990s, low corporate metabolism in Japan has led to shifting resource allocations among companies, which in turn has caused stagnant productivity.

As for Japan's pre-war economy, studies conducted by Kobe University project professor Keijiro Otsuka and National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies Vice President Tetsushi Sonobe find that some 20% to 50% of Japan's pre-war TFP growth was attributable to inter-industry resource reallocations. Meanwhile, approximately half of the increase in labor productivity occurring from 1914 to 1924 was seemingly attributable to inter-firm resource reallocations in a broad sense, including firms entering and exiting the market, according to the author's research drawing on data at the firm level in the cotton spinning industry, a major pre-war industry in Japan.

The second key point with respect to Japan's stagnating productivity is the notion that various relevant investments and changes in social institutions are required in order for a technological shift to precipitate growth in productivity at the macro level.

In his recent book, "The Rise and Fall of American Growth" Northwestern University professor Robert J. Gordon maintains that America's wave of productivity gains and economic growth that persisted from 1920 to 1970 was precipitated by the advent of electricity and the internal combustion engine, two general-purpose technologies (GPTs) that came onto the scene in the latter half of the 19th century. He furthermore asserts that overall lifestyles of Americans underwent substantial innovation, and that in order for such GPTs to yield positive results the nation needed to develop various relevant technologies and invest in infrastructure such as power grids and road networks. This view holds that waves of productivity growth stemming from new technologies are inextricably linked to social transformation.

This point is also consistent with what the Japanese economy has encountered. For instance, the opening of Japan's ports to overseas trade at the end of the Edo period led to a situation where the nation's citizens gained access to various technologies, modern at the time, overnight. This is important because the use of such technologies boosted Japan's productivity and paved the way for transformative change with respect to the nation's social mechanisms and institutions developed in the course of establishing new industries.

During the early years of the Meiji era, Japan went on to eliminate various regulations which had been in force under the nation's feudal political system. This gave everyone the freedom to make their own choices with respect to their occupations, businesses, and places of residence. Meanwhile, companies and factories became prevalent as organizational frameworks around which people were able to coordinate their economic activities. The nation also created universities to act as mechanisms for introducing and improving on technologies, and for facilitating the formation of human capital. The government also established constitutional safeguards with respect to proprietary rights to help ensure that people would have greater incentive to engage in economic activities.

Indeed, these major social transformations largely gave rise to the scenario of Japan's sustained economic expansion, fueled by its productivity gains, emerging at the end of the 19th century.

♦ ♦ ♦

Considering these key points, how should one assess the "New Economic Policy Package" of Japan's current government and the "Future Investment Strategy 2018" under which the policy package has been revised?

First, they seem appropriate in terms of how they emphasize investment in infrastructure in a manner that addresses the rapid development of information and communications technology (ICT). As has been the case with respect to electric power, roads, and other such infrastructure thus far, people will need to have extensive access to fast and high-capacity communications technologies given that such technologies act as an indispensable platform for generating innovation. Moreover, the government is expected to play a role in this regard, given that the associated externalities (effects) are bound to be substantial. It also seems likely that certain measures, geared to appropriately matching human resources to employment and that involve developing labor market infrastructure will help boost Japan's productivity by achieving greater efficiency with respect to resource allocation.

However, there are also some inconsistencies with respect to the policies in terms of certain key points. For instance, universities tend to play a substantial role in fueling innovation, as experience in the U.S. over recent years has shown. This reality is reflected in the wording of the new policy package stating that "higher education is a foundation for knowledge for our citizens, and accordingly acts as a driving force for generating innovation and enhancing our nation's competitive strengths."

Nevertheless, when it comes to implementing policies for making higher education free of charge, the policy states that institutions are to "assign faculty with practical experience to respective academic subjects" as the foremost requirement to be followed by universities eligible for assistance. The policy assumes that the role of universities is that of providing practical education, and is therefore in stark contrast to the notion of a university that would compete with the world's top schools with respect to cutting-edge research by placing sufficient focus on innovation.

Meanwhile, Japan's "Future Investment Strategy 2018" contains traditional industrial policies that include government intervention in private-sector resource allocation, particularly with respect to promoting the agriculture, forestry and fisheries industries, and tourism. This should also cause one to question the strategy's consistency with respect to its objective of achieving productivity growth of the economy as a whole.

The notion of achieving productivity growth through innovation is a very crucial issue for Japan. As such, the government needs to carefully compose and implement reasonable and consistent policies geared to achieving such objectives.

* Translated by RIETI.

February 5, 2019 Nihon Keizai Shimbun