For some 30 years, Japan’s real economic growth rate has remained stagnant, at around 1%. The seriousness of the Japanese economic situation has been highlighted again by the Japan Center for Economic Research’s projection that, by 2023, Japan will be surpassed by Taiwan and South Korea in terms of per-capita gross domestic product (GDP). To overcome the situation, it is essential to increase the value added per worker—that is, labor productivity.

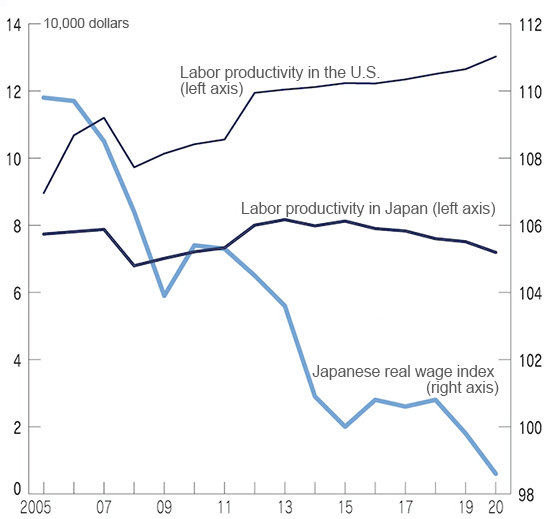

The figure below shows the value added per employee in Japan and the United States on a purchasing power parity basis as represented in real terms by adjusting for the U.S. GDP deflator—calculated by the Japan Productivity Center—and the Japanese real wage index for business establishments with a workforce of five or more employees—cited from the Monthly Labour Survey. While labor productivity has been on an uptrend in the United States since the 2000s, it has remained stagnant in Japan, resulting in a widening gap between the two countries. Over the same period, real wages in Japan have continued to decline.

Source: Japan Productivity Center, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

There is a broad consensus on the view that in order to raise labor productivity in Japan, it is necessary to redistribute resources to sectors and companies with high levels of innovation and productivity. Therefore, this article presents new points of discussion from a historical perspective regarding a mechanism that may cause such a change in Japan.

◆◆◆

In this respect, an estimate of the productivity gap between Japan and the United States on an industry-by-industry basis provides clues for considering those points. According to an estimation by Professor Takizawa Miho of Gakushuin University, who compared the situations in Japan and the United States in terms of value added per hour worked in 2017, labor productivity in Japan was not necessarily lower than in the United States across all industries. For example, in the case of the chemicals industry, labor productivity was 28% higher in Japan than in the United States.

On the other hand, labor productivity is markedly lower in Japan than in the United States with respect to many services industries, including retail and wholesale trade (68% lower) and real estate (73% lower). Moreover, those low-productivity industries account for a large portion of the overall value added in Japan, dragging down the total productivity level of all Japanese industries compared with all U.S. industries.

Another feature of those industries is the large share of small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). According to the 2016 Economic Census, the share of companies with a workforce of 30 or less employees was 48.8% in all industries and 30.3% in manufacturing industries, whereas it was much higher in the wholesale and retail trade industry, at 61.9%, and in the real estate industry, at 60.3%. To raise productivity, it is necessary either to bring up the productivity of SMEs, which comprise a large component of industries, or to shift resources from SMEs to high-productivity industries and companies.

How can that be done? We can find clues in economic history.

One example of an industry whose productivity rose due to the spread of technological innovation among many SMEs is the Japanese textile industry at the beginning of the 20th century. At that time, although the textile industry was a major industry in Japan, it was comprised of many small factories and small household labor forces organized by wholesalers, except for textile factories operated by spinning companies. It was under those circumstances that weaving machines, known as power looms, spread rapidly among small factories at the beginning of the 20th century. Power looms spread at a particularly high pace at factories manufacturing simple products, a typical example of which was the cluster of factories in Fukui Prefecture that were manufacturing the habutae woven silk cloth.

In 1905, no habutae factories were using power looms in Fukui Prefecture, but in 1914, almost all factories there were equipped with power looms. Power looms had a significant impact on productivity. According to my estimation using factory-level data for the period from 1905 to 1914, production volume per worker at factories using power looms was around 2.6 times larger than the volume at factories that were not using power looms, after controlling for the difference in working hours.

Behind this rapid spread of technological innovation were several factors. First, adopting new technology became easier than before. The development of domestic power looms reduced costs, while the expansion of electric power networks improved access to mechanized power.

Second, wages rose. As to the question of when Japan reached the so-called Lewisian turning point, which refers to the starting point of a wage increase in a country until then saddled with surplus labor, the most likely answer is the early 1960s, as suggested by Professor Emeritus MINAMI Ryoshin of Hitotsubashi University. However, Professor Emeritus YASUBA Yasukichi of Osaka University argued that Japan had reached that turning point in the first decade of the 1900s. Indeed, at that time, wages were rising in Fukui Prefecture, and apparently, it was because of the wage increase that the shift to labor-saving technology, which had recently become more easily available, made progress.

Another point I would like to emphasize is that technological change was not only the result, but also the cause of the wage increase. According to a statistical analysis of the impact of the introduction of power looms on the wages of female workers aged 15 or older based on factory-level data for the habutae factories in Fukui Prefecture, wages started to show a significant increase in the year when power looms were introduced for the first time. This can be considered to be a development that reflected an increase in marginal labor productivity due to the introduction of power looms. In short, there was a virtuous circle of rising wages and improving access to new technologies leading to the spread of those technologies, which in turn resulted in a further wage increase.

◆◆◆

Another historical example is the mechanization of agriculture in postwar Japan. KITAMURA Shuhei, an associate professor at Osaka University, paid attention to the fact that at the same time as the rapid spread of tractors among farmers in the 1960s, a large-scale movement of labor from the agricultural sector to non-agricultural sectors occurred. He analyzed the relationship between this phenomenon and the farmland reform that was carried out immediately after the war.

According to his research paper, the factors that led to the rapid spread of tractors were the development of low-cost, high-performance tractors by Honda Giken Kogyo, which is now known as Honda Motor Company, and an increase in landed farmers due to the farmland reform. Farmers who had become landed were highly motivated to improve farm management and actively introduced low-cost tractors. Second and later male children and female children, who became redundant as a result of the rising productivity, moved to non-agricultural sectors.

Another point I would like to highlight is that the 1960s, when tractors spread widely, corresponded with the turning point for the Japanese economy that was suggested by Professor Minami. One possible reason for this is that the acceleration of the wage increase due to the expansion of non-agricultural sectors may have increased the incentives for farmers to introduce labor-saving technology.

Indeed, in the 1960s, SMEs’ capital investment in labor-saving measures increased in manufacturing industries. The 1968 White Paper on Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan pointed out that SMEs’ capital investment activity became vigorous from 1966 onwards and cited “persistent appetite for investment to promote rationalization and modernization in order to adapt to changes in the surrounding environment, such as labor shortages” as one of the motivations.

From those historical experiences, we can extract two important implications regarding the problems facing the Japanese economy today. In both of the abovementioned cases, we see two drivers that triggered a productivity increase for many small manufacturers.

The first driver is a wage increase and the second driver is low-cost access to new technologies. Looking at the current situation of the Japanese economy, we can see that the shrinking labor force provides the necessary condition for a wage increase. The labor shortage caused by the shrinkage and aging of the population could be turned into an advantage and be used as leverage to revive the Japanese economy.

As for the second driver, the necessary conditions will potentially be met as a result of the development of general-use technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics. If low-cost and easily usable labor-saving technologies are developed through the application of such general-use technologies, the condition for the second driver will be satisfied, and this, coupled with the condition satisfied for the first driver, will lead to the spread of those technologies among small businesses and raise their productivity. That will lead to a further wage increase, like the case of the arrival of power looms at the beginning of the 20th century, raising the possibility that the Japanese economy may escape from its prolonged stagnation caused by factors such as low wages and low productivity.

* Translated by RIETI.

February 17, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun