The Subcontract Act was enacted in 1956 for the purpose of ensuring fair subcontracting transactions and protecting the interests of subcontractors. It prohibits various practices such as delaying or reducing payments by main contractors to their subcontractors, refusing deliveries from their subcontractors, unsubstantiated returns, and abuses of buying power. The latest amended Subcontract Act was enacted on May 16, 2025, and it will come into effect on January 1, 2026.

This article explains the key points of the latest revision and summarizes how business relationships will change under the revised law, how relevant companies should work toward fairer transactions, and explains the remaining challenges.

What is noteworthy is the removal of the term “subcontracting” from the name and content of the law. The name will be changed to “Act on Ensuring Appropriate Transactions Involving Small and Medium-sized Suppliers (provisional translation). Under the new terminology, “subcontractors” will be referred to as “small and medium-sized suppliers,” “main contractor” to “clients,” and the “subcontracting payments” to “manufacturing commission payments,” among other changes. The following column uses “subcontracting” and other current terms to remain consistent with the existing law at the time of publishing.

◆◆◆

Under the current law, the applicability of the law is based on the capital size of the companies in question. For example, for transactions related to manufacturing consignment or repair of goods, the law applies to business operators with a capital in excess of 300 million yen who entrust work to another business (including individuals) capitalized at 300 million yen or less, or from business operators capitalized at between more than 10 million yen but not exceeding 300 million yen who entrust work to those (including individuals) capitalized at 10 million or less.

The latest revision adds the number of employees to the classification, leading transactions subject to the law to include “manufacturing consignment or other work from business operators with 300 employees or more to businesses with less than 300 employees.” The addition is designed to prevent large companies from evading the Subcontract Act simply by reducing their capital sizes.

The important purpose of the revision is to break away from the long-lasting stagnation of the Japanese economy. There is a serious concern that the subcontractors are failing to fully reflect the increased costs of raw material, labor and their innovations into their pricing (price pass-through) in the face of coercive behavior by their larger business “partners.” These forced losses result in diminished incentive for innovation, which likely stifles overall national economic growth.

The main points of the revision, which addresses such issues are (1) ensuring appropriate price-setting processes (by prohibiting unilateral pricing decisions without engaging in negotiations), and (2) prohibiting payment by promissory notes. Let’s take a closer look.

First, in addition to existing prohibitions on coercive pricing and unjust price reductions, the revised law prevents main contractors from unilaterally setting unreasonable subcontracting prices which harm the interests of subcontractors despite requests to engage in price negotiations.

A critical issue is to ensure equal opportunities to engage in price negotiations. In some cases, subcontractors may want to avoid detailed price negotiations in the interest of protecting confidentiality or for other purposes. Additionally, it is difficult to objectively determine what constitutes an excessively low price. Therefore, the revised law’s focus on the price negotiation process is appropriate and is expected to contribute to fair pricing, including appropriate cost pass-through.

Second, the use of promissory notes by main contractors will be prohibited for payments to subcontractors. Until now, promissory notes have often been used, and in such cases, subcontractors were unable to receive payments until the notes were settled (under the Subcontract Act before the revision, the payment term of the promissory note had been limited to 60 days.)

As discount fees are deducted by banks for cashing in promissory notes, their use also shifts the cash flow payment burden from the main contractors who issue such notes to the subcontractors. This practice of promissory notes represents an outdated business practice without economic rationality, and thus prohibiting their use under the revision is a welcome advancement.

The revision also includes several other important changes, such as those dealing with business practices in logistics (applying the Subcontract Act not only to transactions between transporters and their subcontractors but also to those between consignors and transportation operators).

◆◆◆

With this revision, subcontractors are expected to gain a stronger position in their transactions, allowing them to secure profits and raise wages by enabling appropriate cost pass-through. The prohibition of promissory notes will also lead to improved cash flow and business performance for subcontractors.

Main contractors must be prepared to lose high-quality subcontractors if they fail to engage in appropriate price negotiations and revisions. The objectives of the Subcontract Act revision are not merely to protect existing subcontractors. What is necessary is the development of a free and fair transaction environment instead of maintaining the status quo.

By ensuring opportunities for fair price negotiations, more productive and innovative companies will be able to remain in or participate in the market, which will promote competition and innovation in their business sectors, ultimately benefiting final consumers.

Of course, long-term, stable business relationships may also have economic rationality and can benefit both parties. When demand and technologies are undergoing significant changes, however, it is desirable for both parties in transaction to be able to flexibly change partners or transaction terms through mutual agreement.

Ultimately, business relationships should not represent a zero-sum game of winners and losers. If ensuring cost pass-through only leads to higher prices for consumers or reduced productivity, it would be counterproductive. The main contractors and their subcontractors are expected to produce synergistic effects through the fusion of their knowledge in price negotiations to promote innovation.

To truly encourage such competition and innovation, the newest legal revision remains insufficient. A key challenge after the revision will be ensuring fair trading practices throughout a product supply chain, from upstream suppliers of raw material to downstream businesses close to final consumers.

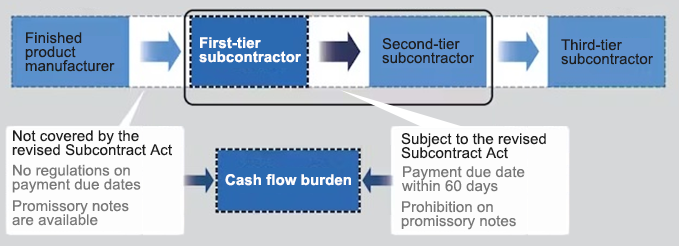

The Subcontract Act covers business transactions between large business operators and small ones. However, a product supply chain includes transactions between large business operators (e.g., finished product manufacturers and their first-tier subcontractors), between large business operators and small ones (first-tier and second-tier subcontractors), and between small business operators (second-tier and third-tier subcontractors). Of these diverse entities, the revised Subcontract Act only covers transactions between large and small business operators that meet the size criteria, excluding all other transactions within the supply chain.

Since the demand essentially starts from the downstream (final consumers), unless large business operators close to the downstream engage in appropriate price negotiations, fair cost pass-through rates cannot be achieved. The intermediaries (the first-tier subcontractors) could be caught in the middle between the second-tier subcontractors that aim to introduce cost pass-throughs and the main contracting business partners (finished product manufacturers) that refuse them.

Furthermore, if large downstream business operators (first-tier subcontractors) that are not protected by the Subcontract Act are forced to receive payment by promissory notes while being unable to use promissory notes for their payment to second-tier subcontractors who are covered by the Subcontract Act, the cash flow burden could be concentrated among the first-tier subcontractors (see the figure).

Thus, promoting fair trading practices throughout the entire supply chain, including transactions outside the coverage of the revised Subcontract Act, remains an important challenge.

Finally, the issue of large business operators infringing on the intellectual property rights and know-how of smaller partners has not been sufficiently discussed. This is another challenge for future consideration.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

September 30, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun