Discussions have begun on the formulation of Japan’s seventh Strategic Energy Plan. The plan is based on the Basic Act on Energy Policy, which was enacted by members of the legislature in 2002. Under the act, the first Strategic Energy Plan was formulated in 2003 and it specified three fundamental principles – securing stable energy supply, environmental suitability, and utilization of market mechanisms.

Since then, the plan has been revised approximately every three years in line with the changing energy situation. With the significant progress that has occurred in energy system reform since the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, the plan has placed an emphasis on energy efficiency improvements by utilizing market principles.

The seventh plan will envisage energy supply and demand towards FY2040. As the effects of the electricity system reform, which was completed in 2020, have gradually become apparent, the roles that the plan is expected to play have been changing. In the following, I would like to discuss three points that should be taken into account in the new plan.

◆◆◆

First it is necessary to reaffirm the roles of the Strategic Energy Plan as a tool through which the industry and government sectors can share a vision. Even if the plan shows future energy supply and demand under a liberalized energy market, there is no guarantee that the planned energy supply and demand will be achieved.

However, the liberalization fragmented the electricity market and separated the electricity power generators from transmitters. Thus, business operators that are capable of taking a panoramic view of area-by-area supply chains no longer exist. This makes it increasingly important to support investment prospects and incentives by encouraging business operators to share the future picture of Japan’s energy supply and demand.

The projection of future demand is an important factor in creating an investment plan. In the past, local power monopolies were able to forecast their sales over a long period of time and secure fuel such as liquefied natural gas under long-term contracts.

As the electricity retail market was fully liberalized in 2016 and the separation of power retailers from generators proceeded, some retailers have lost market share to others or had to procure electricity on their own in the market. As future sales become more difficult to forecast, power generators have no choice but to reduce the amount of fuel purchased under long-term contracts, and incentives to invest in power generation equipment has diminished.

As the liberalization has made it impossible for businesses to easily predict future demand, forecasting future demand in Japan can greatly assist power equipment manufacturers, power generators, and financial institutions, encouraging their investment in long-term power generation projects that last for 40 to 50 years.

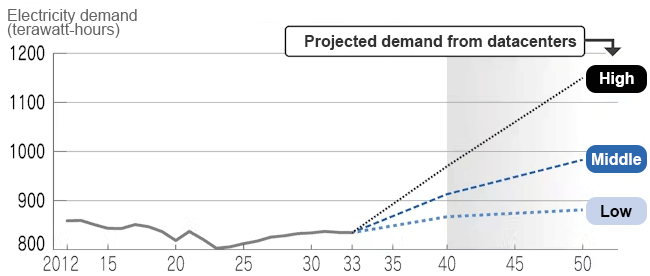

Regarding future electricity demand projections, it is predicted that the widespread adoption of generative artificial intelligence will lead to a significant increase in semiconductor production and datacenter construction. On the other hand, it has been pointed out that total electricity demand may actually decrease due to a declining population and increasing energy efficiency and conservation.

An analysis of a document published after a study meeting of the Organization for Cross-regional Coordination of Transmission Operators, Japan, which was established within the electricity system reforms, shows that electricity demand in 2040 is expected to increase by about 10% even in a conservative scenario, although the demand forecasts differ significantly between scenarios. This indicates that power generators are required to invest in additional capacity while replacing existing aged facilities.

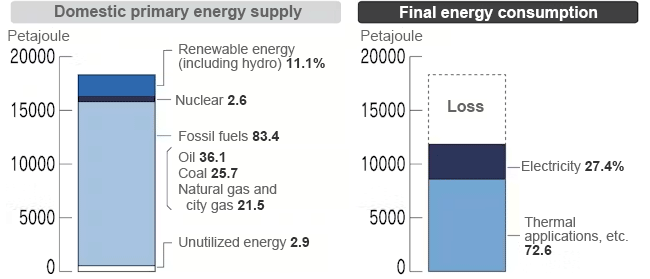

The second point is the growing importance of stable supply and decarbonization. Japan has the lowest primary energy self-sufficiency rate among the Group of Seven major countries at 13.3% (FY2021), so it will have to depend on fossil fuels for the time being while attempting to reduce its dependence on overseas sources.

Since Russia's aggression against Ukraine, geopolitical risks have emerged regarding the procurement of fossil fuels such as LNG and uranium. Meanwhile, increasing energy demand from countries such as China and India raise the risk of Japan being outbid in future fuel procurement.

Efforts to achieve carbon neutrality (net-zero greenhouse gas emissions) by 2050 will accelerate in the future. While Japan has declared a target of cutting GHG emissions by 46% in FY2030 from FY2013, a declaration of the G7 Hiroshima Summit in 2023 and the Sixth Assessment Report of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have called for a 60% reduction from 2019 levels in 2035. In light of the G7 declaration and the Assessment Report, Japan could potentially increase its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) for 2035, which will be set in February 2025, to a 66% emissions reduction from FY2013 levels.

Japan has collected more than 20 trillion yen in feed-in-tariffs from electricity bills to purchase electricity from renewable sources, doubling the renewable percentage share of total power generation to about 20% over the past decade. Further increases to the renewable energy share through such measures as the spread of offshore wind power generation will take time.

Given this situation and future demand projections, it is indispensable for Japan to invest in new decarbonized thermal power generation capacity. Cost-effective methods should be chosen based on total costs, including fuel production, transportation, acceptance and distribution, while preventing existing facilities from becoming “stranded assets.”

Although there is a tendency to focus on hydrogen/ammonia-fired power plants, the use of synthetic methane (e-methane), which emits virtually no CO2, and carbon capture and storage technology should also be considered.

◆◆◆

The final point concerns perspectives on industrial policy. While electricity accounts for about 30% of Japan’s final energy consumption, the remaining 70% is used in thermal applications such as automobiles, water heaters, driers, and industrial furnaces, which all burn fossil fuels. The transportation and industry sectors represent a majority of the demand for thermal applications, and the companies involved are largely small and medium-sized enterprises. The electrification of such thermal applications and the decarbonization of industrial processes will be indispensable for achieving carbon neutrality.

The decarbonization of manufacturing processes should be advanced in coordination with the development of decarbonized supply chains which are specific to each industrial location and cluster. Local governments play a major role here. For example, the Tokyo metropolitan government is implementing various initiatives to create demand for hydrogen for commercial vehicles and around Haneda Airport. Such local government initiatives should be combined with the national government's GX (Green Transformation) initiative to explore new avenues of collaboration between national and local governments.

Relying solely on foreign resources such as hydrogen and ammonia for decarbonization will not lead to any increase in Japan’s energy self-sufficiency but encourage a further outflow of national wealth. A stable supply of affordable energy is required for protecting the livelihoods and employment of Japanese citizens. Decarbonization should be promoted along with Japan’s economic growth from the perspective of industrial policy.

The feed-in-tariff system, which has created a large burden on the public, has largely been utilized for solar power generation projects using foreign products, failing to develop domestic industry. In the past, Japan was forced to purchase GHG emission credits worth some 1 trillion yen due to its failure to achieve a 6% cut in emissions under the Kyoto Protocol, while major countries like the United States and Russia withdrew from the protocol.

Dring the Global Stocktake (GST) at the 28th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2023 (COP28) which assesses the progress toward decarbonization, it was revealed that Japan made progress in reducing emissions in line with its target, while many countries emitted greenhouse gases beyond their respective targets. The government should formulate a flexible Strategic Energy Plan that serves Japan’s national interests while preventing our earnest efforts at achieving our commitments from going to waste.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

June 20, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun