The power squeeze that struck eastern Japan on March 22, 2022, stirred worries among the Japanese people. The government issued the first-ever alert over the severe tightening of the electricity supply-demand balance against the backdrop of unforeseen events such as the unseasonal cold wave and the shutdown of some power plants affected by an earthquake that had jolted northeastern Japan several days before.

Given that a similar crisis occurred in the 2020 winter season due to a shortage of stocks of liquefied natural gas (LNG), which had triggered a market price upsurge, power supply-demand squeezes have apparently become a chronic problem. The electricity crisis, combined with concerns over fuel procurement due to the deterioration of the Ukraine situation, has raised calls for further reform of the electricity system from the viewpoint of maintaining stable supply.

In Japan, the electricity system reform started after the rolling blackouts took place in eastern Japan in 2011, due to the impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake. The reform was completed two years ago.

By dismantling the vertically integrated system that was controlled by major power companies, the electricity system reform aimed to enhance competition in the electricity generation and retail sales sectors. The full liberalization of retail sales has given consumers a wide range of options. The management of power companies has started to change, albeit gradually, from the supplier’s point of view to the customers’ point of view. Those are among the significant results of the reform.

On the other hand, ensuring stable supply is an essential responsibility of the electricity industry. Even when an accident occurs, power supply must not be disrupted. In order to avoid excessive dependence on foreign sources for the supply of fuel and ensure secure power supply to consumers, avoiding power outages by matching power supply and demand on a second-by-second basis has been upheld as an important policy goal.

At first glance, economic efficiency and stable supply may appear to be at odds with each other. Although it is not desirable to have excess capacity from the viewpoint of economic efficiency, stable supply requires the possession of excess capacity as a precaution against a possible tightening of the supply-demand balance.

From the beginning, economic efficiency has been strongly promoted under the electricity system reform. Perhaps that reflected the optimistic view, based on the assumption of the presence of sufficient capacity, that even if economic efficiency was promoted fairly strongly as a policy initiative, stable supply would not easily come under threat.

However, recurring natural disasters, including the 2018 Hokkaido Earthquake and major power outages, have reminded us of the importance of a stable power supply. A legal amendment in April 2022 provided for institutional arrangements to facilitate prompt post-disaster recovery. The remaining challenge is how to ensure stable supply in non-crisis periods.

Below, I will discuss three interrelated challenges in relation to the stable supply in non-crisis periods.

◆◆◆

The first challenge is developing a system that supports stable supply that allows for the adoption of renewable energy as a major power source. In Japan, electricity suppliers are required to secure a reserve stockpile sufficient to make up for a possible supply shortage due to an extreme heat or cold event that could happen once every 10 years, with the required reserve stockpile level set at 3% of overall capacity.

However, as renewable energy, mainly in the form of solar power, gradually becomes a major power source, the reserve stockpile necessary for compensating for output shortages on cloudy and rainy days has been increasing. As indicated by the supply squeeze in March, the supply-demand balance may become tight outside of times of severe heat or cold. It is necessary to develop a system to more meticulously calculate and procure the necessary reserve stockpile not only at times of extreme weather events, but on a routine basis.

On the other hand, on sunny days, solar power generators produce electricity in excess of demand, resulting in surplus power supply. Therefore, output is controlled in order to prevent oversupply from causing power outages. Active efforts should be made on the operation side to devise methods of eliminating the need for such output control. One effective way of doing that is lowering electricity rates for daytime hours on sunny days, when more solar light is available, in order to boost demand. Another is using digital technology to flexibly stimulate demand—e.g., introducing smart meters (next-generation electricity meters) to encourage users to change their power consumption behavior in accordance with their respective needs. If the lower limit on market electricity rates, set at 0.01 yen/kWh, is removed and if negative rates are allowed, the incentive to use solar power electricity at times of surplus supply will grow.

The second challenge is how to address the shortage of investments in power sources. As a trend, fossil-fuel thermal power plants, which account for around 80% of overall electricity generation in Japan, are becoming less and less profitable in line with an increase in solar power electricity generation and are being retired. The trend has been accelerated by the decarbonization movement. While the retirement of inefficient coal-fired power plants is being promoted as a policy initiative, it is difficult to obtain financing from financial institutions for fossil-fuel thermal power plants. As a result, when the supply-demand balance has tightened, electricity cannot be supplied in sufficient amounts, and the supply squeeze, coupled with rising fuel costs, leads to an upsurge in the market price.

Electricity retailers, which are overly dependent on procurement from the market, not only find it difficult to secure sufficient supply, but also struggle with a negative spread—a state where the procurement cost is higher than the sales price—with the result that some companies have opted to discontinue accepting new customers or to stop doing business altogether.

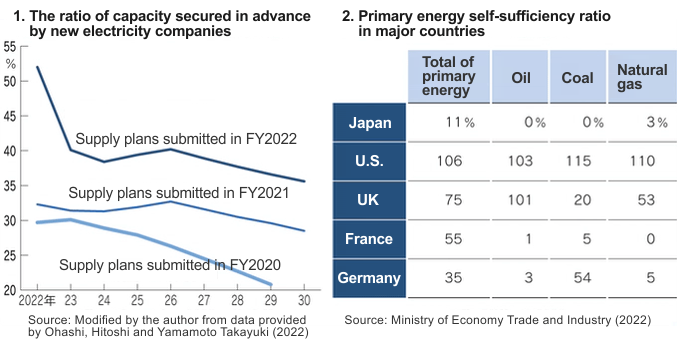

Electricity retailers are obligated to secure the supply capacity necessary for sales to meet users’ demand. However, new electricity companies have not secured even half of the necessary supply capacity, with many of them depending on spot procurement from the market (see Figure 1).

In Japan, a capacity market has been established where electricity supply that will be available four years in the future is traded, as a scheme to encourage investment in electricity generation by providing a long-term outlook on future revenues while holding down excessive increases in market price. However, as the effects of that market will only start to appear in 2024, concerns over supply capacity will remain until then. Indeed, the prospects for the supply-demand balance in FY2022 are harsh. In particular, it will be difficult to secure the necessary reserve stockpile in the winter of 2022-2023 over a large area stretching from Tokyo to Kyushu.

It is necessary to take additional measures to secure supply, such as restarting temporarily closed and retired fossil fuel thermal power plants and introducing staggered schedules for power plant maintenance and inspection while strengthening the enforcement of the obligation for retailers to secure the necessary supply capacity.

◆◆◆

The third and last challenge is fuel procurement. Japan’s primary energy self-sufficiency ratio is 11%, the lowest among the G7 countries (see Table 2). Amid the upsurge in spot energy prices in international markets due to the deterioration of the Ukraine situation, among other factors, Japan should aim to conclude long-term procurement contracts at relatively low prices as long as it is dependent on overseas resources.

Laying the foundation for ensuring that suppliers can earn profits from procured fuels is a quick way of encouraging long-term fuel procurement. Among the options for achieving that are invigorating futures trading and promoting negotiated transactions between electricity generation companies and retailers. As those options are also useful for securing financing for investments in power sources, they would additionally be effective in resolving the shortage of such investments.

Because of the prolongation of the Ukraine crisis, there are concerns that a fuel procurement shortage, coupled with a price upsurge, will occur again, as it did in the winter of 2020. Promoting domestic development and production of decarbonized fuels, such as synthetic fuels and sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), in addition to securing power sources that are not susceptible to overseas fuel market conditions, are important for maintaining stable supply.

Carbon neutrality (net zero emissions of greenhouse gases) cannot be achieved through efforts made in the electricity sector alone. In the area of agricultural policy, too, it is necessary to accelerate nationwide decarbonization efforts, such as incorporating production of fuels from agricultural products into the concept of stable supply. Such efforts will also help to resolve long-pending challenges, such as securing sufficient manpower in the agricultural industry.

While the electricity system reform was completed in 2020, work remains to be done from the viewpoints of stable supply and decarbonization. A subsequent reform is needed in order to rebuild the foundation for stable supply with a view to further improvements in economic efficiency and decarbonization.

* Translated by RIETI.

May 20, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun