The names and priorities of government-led regional development measures in Japan have differed with different administrations. The previous names of such measures include the New Industrial City program during the period of high economic growth, the Technopolis Plan after the oil crisis, and the "Furusato Sosei" (homeland recreation) initiative of the Takeshita administration.

Regional development measures in the past almost always aimed to correct the overconcentration in Tokyo. The Regional Revitalization initiative since the Abe administration has also focused on correcting the overconcentration problem, promoting the decentralization of government agencies and the relocation of private companies’ head office functions through tax incentives. Under the current Kishida administration, the "Vision for a Digital Garden City Nation" has become a priority policy for regional revitalization.

Given the recent population migration trend and economic indicators, however, it is difficult to conclude that the overconcentration in the Tokyo area is on the verge of resolution. According to the national census, the Tokyo area’s share of Japan’s population increased by 1.5 percentage points from 27.8% in 2010 to 29.3% in 2020. While the concentration of population in the Tokyo area has continued, Japan’s population has declined since the peak around 2008. The resulting population decline in rural areas is making it difficult to maintain rural transportation infrastructure, such as railways.

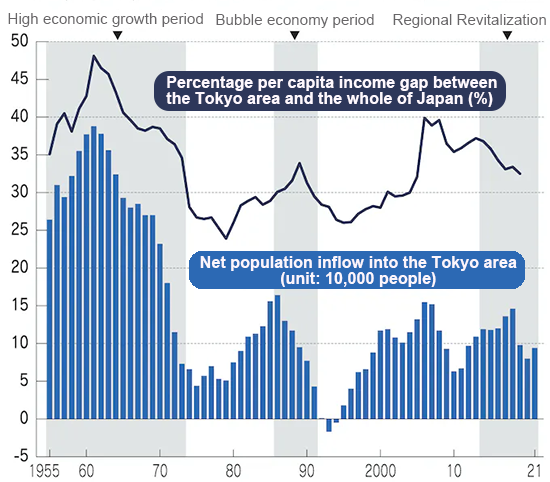

The population migration trend under the COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 represented a suspension of the net population inflow into the Tokyo area due to the spread of telework. As COVID-19 infections have subsided, however, the recent net population inflow into the Tokyo region shows that the population migration to rural areas under the COVID-19 pandemic was a temporary phenomenon that failed to be accompanied by the reduction of income gaps between Tokyo and other areas.

◆◆◆

From several perspectives, we should reconsider regional development policy objectives and the disparity between Tokyo and other areas that has not been resolved despite repeated national government measures for correcting the overconcentration.

The first question to ask is whether an equilibrium between population inflow into and outflow from the Tokyo area is an adequate policy objective. While the reasons for interregional population migration vary, there is a strong correlation between long-term migration and income disparity (see the chart below).

Sources: "Prefectural Economic Accounting ," Cabinet Office, and "Internal Migration in Japan Derived from the Basic Resident Registration ," Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications

The movement of individuals to highly productive regions is coupled with business metabolism to increase growth potential. Population migration is an essential condition for metabolism. Trying to forcibly achieve an equilibrium between people moving into and out of a region may undermine the vitality of Japan as a whole. It is important to reduce income disparities by proactively increasing rural areas’ earning power (value-added productivity).

Next, the strategy of regional revitalization has always focused on improving rural earning power. The question is whether earning power has been adequately interpreted. Earning power often refers to the value of a company’s shipments or sales. In particular, it is the power to acquire funds from other areas. Attracting companies to an area is a shortcut to acquiring funds, while also increasing employment to some extent.

However, we have to question how much funds has actually been left in an area and how local employment has increased irrespective of job changes. The ultimate question is whether the destinations of earned funds have been identified. By identifying the destinations and quantifying the funds left at these destinations, we can clarify the economic effects of attracting a company’s head office with indirect departments to an area.

Some municipalities create municipal-level input-output tables when implementing their local strategies. These tables are used for measuring spillover effects in policy evaluation. Greater ripple effects may indicate that many economic entities are involved in some policies. However, in order to determine the actual “earning power” benefits, it is important to measure the amount of funds that remains in the region.

In other words, earning power is reflected in the regional economy by the amount of value added that remains in the region. Without any increase in the value, there is no regional development (elimination of disparities). Earning power is not limited to private companies. Local government revenues from the use of public facilities and from the so-called Furusato Nozei (hometown tax donation) program may also represent earning power, although the program has some problems to be resolved.

◆◆◆

It is also essential to implement multi-track measures that link earning power to other policy goals. In particular, small-scale municipalities that are suffering from population decline are required to link industry promotion to natural population growth.

In Nishiawakura Village, Okayama Prefecture, there is a public-private joint venture called A Zero Group Nishiawakura Mori no Gakko that uses a closed elementary school building. It serves as the village’s core industry organization and produces lumber and wood products. The organization serves as a trading company for housing materials and as a regional agency, developing urban antenna shops that sell the Nishiawakura brand.

It creates added value by utilizing local forest resources, attracts money to the region through sales and services outside the region, and attracts human resources related to manufacturing wood products from urban areas, producing multiple effects.

In addition, the company in 2016 began to farm eels using wood chips from logging. The environmental and economic cycles have earned money from outside the region and created employment. Additionally, the number of elementary school students has been increasing due to the inflow of young people, while the economic cycle from upstream to downstream has formed a new industrial structure, leading to an increase in the number of school children in the area.

While successful example cases of regional revitalization exist, imitating their success may not be simple due to the variation that exists between regions in terms of environments, histories, and resources, and people.

The problem is how to find and refine tangible and intangible regional resources that can serve as the basis for core industries. This includes reviving weakened local industries and attracting candidates for core industries from outside. By identifying core industries to develop and enhancing connections between industries, we should be able to improve the spillover effect on local markets and industries. For this purpose, economic structural analysis using regional input-output tables is indispensable.

In Izumi City, Kagoshima Prefecture, which has a population of about 52,000, I and a local think tank created an input-output table two years ago and conducted an analysis to visualize the strengths and weaknesses of the regional economy. Based on the results, we have proposed and been implementing measures for improving local agricultural productivity and a plan to create an information service for independent planning.

While some local governments aim to revitalize their regions through inbound tourism, Taketomi Town in Okinawa Prefecture is trying to transform its regional industrial structure from one centered on tourism-related industries into a new industrial structure by creating an input-output table to enhance the effectiveness of the Basic Plan for Tourism Promotion formulated in March 2023.

The idea of developing core industries to create a new industrial structure is based on Ricardo's theory of comparative costs. When focusing on industries with comparative advantages, however, we should examine relevant marketability by checking whether there is sufficient potential demand and whether there is a price advantage. If demand is small, earning power may not increase regardless of the cost.

If there is no price advantage, we should differentiate goods to counter the absence of price advantages. This means developing goods for which substitutes have low price elasticity. Such goods may not be substituted through minor price changes.

As individual municipalities only have limited natural population growth, their measures to attract people from outside may result in competition for a small slice of the pie of available migrants. In the midst of fierce survival competition, local governments that create new industrial structures that are linked to the number of births will become sustainable. By simulating the effects of policy alternatives, we would like to visualize new local industrial structures. Efforts to do so will lead to regional revitalization from rural areas.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

June 26, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun