The runup to the U.S. presidential election in November has become chaotic following incumbent President Joe Biden's poor performance during his June debate and the subsequent attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump. But whoever wins the presidential election, the United States’ China trade strategy will likely remain mostly unchanged. Incumbent U.S. Trade Representative Katherine Tai and her predecessor Robert Lighthizer in their respective speeches in June admitted that Presidents Trump and Biden share similar views on China.

◆◆◆

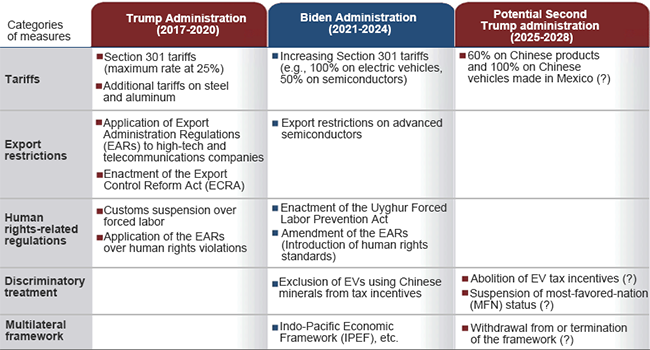

In fact, major trade measures against China under the Trump and Biden administrations have a high degree of continuity, as shown in the table below.

[Click to enlarge]

First, the Biden administration retained tariffs imposed by the Trump administration under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. In May, the Biden administration announced its intention to raise the top tariff rate from 25% to 100% on electric vehicles (EVs) and 50% on semiconductors. It has also retained the additional tariffs initiated by the Trump administration on steel and aluminum products under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962.

The Biden administration's tightening of export controls on advanced semiconductors since October 2022 also originated from the enactment of the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) in 2018 under the Trump administration, the addition of Huawei to the entity list subject to the de facto embargo in 2019, and the application of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) to semiconductors and related technologies.

The Trump administration applied the EARs, which were originally intended for national security, to Chinese companies, because of their contribution to political repression of the Uyghur people and of Hong Kong. This led to the Biden administration's revision of the EARs to establish human rights standards for the EARs. The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which came into effect in June 2022, amounts to an extension of the customs suspension activated by the Trump administration for Chinese products on the grounds of forced labor.

However, the Biden and Trump administrations have sharply differed over how to cooperate with U.S. allies. The Biden administration has launched the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) to build an anti-China network. Regarding export controls for the purpose of human rights protection, it has developed cooperation frameworks such as the Export Control and Human Rights Initiative and the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council. These types of measures were not seen under the Trump administration.

Regardless of who will become the next president, however, there will be no major changes in the hardline U.S. stance toward China. Washington will continue to furiously brawl with Beijing in defiance of World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. However, President Trump is feared to be leaning toward even more symbolic and radical measures, advocating a "strategic decoupling" from China as Lighthizer proposed in his recent book.

In fact, President Trump is known for presenting what he refers to as "tariff man" ideas. First, he has vowed to impose a universal basic tariff of 10% on all imports, a 60% tariff on Chinese products, and a 100% tariff on Mexican-made cars produced through Chinese direct investment. The current Section 301 tariffs are still within 25%, excluding higher ones on some products such as EVs, but they could be significantly increased if a second Trump administration comes to power.

Second, President Trump could suspend the Most Favored Nation (MFN) status for China. Before China's accession to the WTO in 2001, the U.S. Congress had reviewed the MFN status for China on an annual basis. For the U.S. Congress, granting China MFN status permanently was not necessarily a given fact. However, all of these extreme ideas may simply be aimed at winning the election and their implementation is uncertain.

On the other hand, it is possible that some policies that are unfavorable to China might not continue for various different reasons. President Trump, who is not a proponent of free trade, has hinted at withdrawing from IPEF in an attempt to contain China. The framework for "friendshoring" which involves the U.S. building supply chains with friendly countries could also be at risk. Additionally, based on his strong stance against decarbonization, the Trump administration may abolish existing tax credits for EVs.

◆◆◆

With regard to the continuation or escalation of U.S.-China frictions and resulting impacts on Japan, I would like to highlight the following two points from the perspective of the international trade order.

The first is the impact on the development of the trade order in East Asia, including China. At a Japan-China-South Korea summit meeting in May, the three countries agreed to accelerate negotiations on a high-quality free trade agreement (FTA). However, if President Trump is reelected and pressure to decouple from China increases, it may be difficult for Japan to pursue such economic partnerships with China. If the three countries were aiming for a high-level FTA, China might demand access to strategic goods such as semiconductors, for which Japan currently cooperates with the U.S. on export controls, making it difficult for the three countries to reach a high-quality FTA.

The second issue is the impact on the maintenance of the WTO regime. The WTO's Dispute Settlement Panel has already found the U.S. Section 301 tariffs and steel and aluminum tariffs as counter to WTO rules; however, the United States has refused to abolish them. If President Trump is reelected, there is a risk of intensified trade conflict.

In late June, 16 Nobel laureates in economics expressed concern about the negative impacts of President Trump being reelected on the U.S. economy. Paul Krugman warned that high tariffs would send a negative message that the United States is no longer capable of leading the global economy.

In particular, MFN status and tariff rules are core principles of the WTO agreements, which advocate for free and non-discriminatory trade. If the United States openly ignores these principles, the WTO regime itself will inevitably be further marginalized. Furthermore, reforms to the WTO Appellate Body, which could potentially hinder U.S. trade restrictions on China, would likely be derailed. This would be a significant blow to Japan, which is highly dependent on the WTO regime.

If the U.S.-China friction continues for another four years, Japan, which relies on the rules-based multilateral free trade system, will need to work with other middle powers to maintain the WTO regime.

If the United States is reluctant for the WTO Appellate Body to resume its functions, the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) established by like-minded countries should be used to restore dispute settlement rules, albeit in a limited manner. Given that China is a party to the MPIA, it may be used to contain China’s economic coercion.

On the other hand, Japan should contribute to WTO reform as a member of the Ottawa Group, which consists of Canada and other reformist and solid middle powers and the European Union (EU).

In addition, despite their trade conflict, the United States and China are highly interdependent, which means that the WTO to which both belong remains an avenue for reconciling their interests. The agreement on patent exemptions for COVID-19 vaccines and the fisheries subsidy agreement in 2022 demonstrated that the United States and China can compromise when it comes to dealing with global challenges like the pandemic.

The United States and China have also agreed to cooperate on climate change. In the future, if meaningful cooperation is established on climate change between the United States and China through the WTO's Trade and Environmental Sustainability Structured Discussions, it will contribute to the restoration of the WTO's negotiating function. Japan should strive to produce an agreement on such U.S.-China cooperation.

However, if President Trump, who is known for his thorough anti-WTO and anti-decarbonization stance, is reelected as U.S. president, it may be difficult to envision such a scenario.

As a “Plan B” of interregional cooperation to replace the WTO, Japan should focus on revisiting the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which came into effect in late 2018, in which neither the United States nor China are contracting parties.

As the United States has already turned cautious about WTO and IPEF negotiations on digital trade rules, updating the CPTPP rules first could pave the way to a future WTO agreement. In addition, the CPTPP members should try to increase the number of CPTPP participants and cooperate with the EU, South America’s Southern Common Market known as MERCOSUR, and other major economic blocs.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

July 17, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun