During the campaign for the election of the LDP leader in September, one of the leading candidates, Mr. Shinjiro Koizumi, pledged to reform dismissal regulations and sparked much controversy. Another candidate, Mr. Taro Kono, also advocated the introduction of monetary settlements for dismissal. Thanks to these actions, legal system reform related to dismissal is now attracting attention.

An opinion poll conducted by Nikkei Shimbun in mid-September 2024 shows the division of public opinion on the easing of dismissal regulations for regular workers, with 45% answering that the current regulations are too strict and should be eased and 43% answering that the current regulations should be maintained. In this article, I aim to present reasons why regulatory reform governing dismissal is necessary and what reforms would be preferable.

◆◆◆

There is a perception that dismissal regulations in Japan are overly stringent, which has led to the recent push for reforms to Japan’s dismissal laws. However, while some argue that based on the OECD’s strictness index, Japan’s laws are less strict than the average value of the index, the argument is not necessarily accurate.

As monetary settlements are not recognized as a remedy for unfair dismissal in Japan, the OECD index treats Japan’s system as lacking the settlement payments. For this reason, compared to other OECD countries, where several months’ salary of restitution is recognized as legitimate, Japan’s dismissal costs can be seen as being lower.

In practice, due to Japan’s lack of an official monetary settlement framework, the only remedy for unfair dismissal in Japan is reinstatement to the original post. However, in reality, workers rarely return to their former companies after litigation and most cases are eventually resolved with some form of monetary settlement. The lack of standardization and transparency surrounding those cases often leads to disputes.

For companies that consider the possibility of a dispute itself as a reputational risk, dismissal is a highly risky option. In other words, the perception that dismissal regulations are strict in Japan originates from the uncertainty about what happens if a dispute arises.

Let me explain the growing demand for legal reform in this area. Companies have been continuously adapting to changes in demographics, technological advancement, environmental regulations, and the like. For example, traditional heavy electric machinery manufacturers have evolved into companies that integrate digital technology and infrastructure. Such business transformations naturally bring about changes in employee roles and responsibilities.

In Japan, large companies address these business transitions by reassigning existing employees. In contrast, large companies in the United States tend to resort to laying off employees in declining business areas and hiring new employees to undertake the new roles, facilitating these changes.

Episodes regarding the introduction of industrial robots in the 1980s and 1990s in Japan and in the United States illustrate this difference. When inexpensive robots became available, Japanese automakers guaranteed employment through the reassignment of existing employees and were able to introduce those robots without facing strong opposition from labor unions. In contrast, US automakers faced strong opposition from labor unions which feared layoffs, delaying the adoption of robots.

Determining whether the Japanese or US employment practice is better depends on various factors, such as the importance of affinity between workers and their jobs, ease of retraining workers, and the fluidity of labor mobility across companies. It also depends on the nature of each business, meaning that the optimal solution may vary by company.

Nevertheless, the strictness of dismissal regulations plays a significant role in the decision-making process. According to a study comparing Germany and the United States by Professor Toshihiko Mukoyama of Georgetown University, et al., job transitions within the same company are more common in Germany, while those across companies are more common in the United States, and this difference can be explained by the variation in strictness of dismissal regulations between the two countries.

If the opacity of Japan’s dismissal regulations is forcing many companies to rely on internal reassignment to adjust to changes in the business environment, making the system more transparent and developing an environment in which companies can make choices tailored to individual circumstances is obviously necessary.

In order to enhance the transparency of dismissal regulations in Japan, it is necessary to establish monetary settlements as a remedy for unfair dismissal and set the settlement amounts in advance.

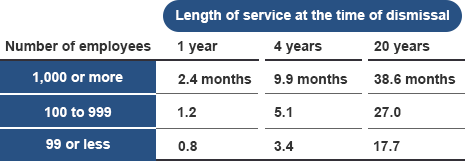

University of Tokyo Associate Professor Keisuke Kawata and I propose the use of a “Complete Compensation Rule,” in defining the settlement amounts. This rule would use the calculation of the difference between the lifetime income that a worker would obtain by continuing to work for the present company and the lifetime income that the worker would obtain after changing jobs. We calculated how many months of salary the standard would be at the time of resignation (see the Table below).

(Source) Reconsidering Unfair Dismissal in Japan: Design of Monetary Compensation System; edited by Shinya Ouchi and Daiji Kawaguchi.

Monetary compensation increases with tenure because it depends on increases in wages in accordance with the years of service. As wage growth is larger for large companies, settlement amounts are larger in large companies.

Many regular workers in Japan endure long working hours, accept job transfers nationwide, and endeavor to improve their skills, in anticipation of employment security and future wage increases.

Relaxing dismissal regulations in a way that discounts this social contract would be both unfair and politically difficult to achieve. Instead of attempting a major reform of the current dismissal framework that is aligned with Japanese employment practices, a more realistic approach is to introduce a monetary resolution system and enhance transparency.

It is preferable to adopt this system and implement a mechanism to adjust the standards for settlement money based on objective indicators, such as changes in the relationship between the length of service and the wage amount.

◆◆◆

Critics have raised concerns regarding this proposal and I would like to respond to those concerns. First, Professor John Mark Ramseyer of the Harvard Law School in the United States criticized it as a proposal to strengthen dismissal regulations. However, we consider our proposal to be realistic for enhancing transparency while maintaining current regulatory levels. If a business restructuring plan involving the dismissal of employees convincingly describes future revenue growth, management must be able to secure funds for settlements.

Looking back on discussions on dismissal-related legal systems over the last 20 years or so, some may consider that current discussions will also fail. However, discussions on policies that affect many stakeholders naturally take time. As shown in the results of the opinion poll mentioned above, the situation is actually changing. By focusing on the introduction of the monetary settlement system for unfair dismissal, we may also be able to prevent a rehashing of the debate.

Despite labor shortages dominating the concerns in the current labor market rather than labor surplus, some point out that dismissals are less relevant in the current context. Critics overlook the diversity of jobs and workers. Looking at the actual status of job offers and job seekers, the jobs-to-applicants ratio for engineers is increasing amid digitalization, but that for clerical roles has stagnated, showing a shift in the occupational structure. Even amid current and future labor shortages, dismissals will occur due to the degree of transformation.

Another issue is whether to allow employers to initiate monetary settlements. I consider it preferable to also allow employers to initiate the process. Due to the nature of monetary settlement as a remedy for unfair dismissal, it is generally thought that claims should be restricted to workers.

However, restricting the claims exclusively to workers effectively grants them veto power over monetary settlement, potentially creating bottlenecks and undermining the effectiveness of the system. Therefore, the system should be designed to allow both employers and workers to initiate claims for monetary settlements.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

November 1, 2024 Nihon Keizai Shimbun