On September 25, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and U.S. President Donald Trump signed a joint statement confirming final agreement on the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement and the Japan-U.S. Digital Trade Agreement. That was only one year after they agreed at their summit meeting on September 26, 2018, to start negotiations toward concluding the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement on Goods (TAG). On October 7, the representatives of the Japanese and U.S. governments formally signed those agreements.

On the U.S. side, the agreements will be put into force without Congressional approval based on special measures such as the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) laws. On the Japanese side, the agreements are expected to be put into force in January 2020 at the earliest, subject to approval in the extraordinary session of the Diet. In this article, I will summarize the key points of the two agreements and explain their implications and the outlook on future trade negotiations.

♦ ♦ ♦

First, I will discuss the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement, which concerns goods trade. The United States withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) immediately after President Trump took office. The Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement is based on the contents of the TPP (which were worked out in 2015).

Below, the contents of these two agreements will be compared. On agricultural, forestry and fishery products, a joint statement issued one year ago stipulated that with regard to those products, the market access to be agreed on under the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement should not be greater than the access agreed on under Japan's previous economic partnership agreements. In the United States, there were hardline arguments calling for Japan to provide better market access than the access agreed on under the TPP. However, the market access agreed on under the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement turned out to be almost the same as that under the TPP with respect to beef, pork, wheat, barley, whey, cheese, wine and so on. With respect to rice, the introduction of a tariff-free quota like the quota agreed on under the TPP was not included in the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement.

In addition, all wood and fishery products, for which tariffs have been reduced or eliminated under the TPP, were excluded from the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement. The Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement in effect allows an increase in beef exports from Japan to the United States. On the other hand, the two countries agreed on the reduction or elimination of tariffs on export products of interest for Japan (a total of 42 items, including soy sauce, Chinese yam, persimmon, melon, cut flowers, and "bonsai" potted trees).

As for industrial products, the two countries agreed on the reduction or elimination of U.S. tariffs on 199 items, including machine tools and advanced technology products. However, the elimination of U.S. tariffs on Japanese automobiles and auto parts, which have the largest share (29%, worth approx. 4.5 trillion yen) and the second largest share (6%, worth approx. 930 billion yen), respectively, of the total value of Japanese exports to the United States, is subject to further negotiation. In contrast, the TPP requires tariffs on passenger cars (2.5%) to be phased out over a 25-year period and tariffs on trucks to be phased out over a 30-year period. Tariffs on more than 80% of auto parts must be immediately eliminated. Compared with the TPP, it must be said that the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement is much less advanced than the TPP with respect to the reduction of tariffs on auto parts.

The Japanese government stated that cabinet ministers had confirmed that the United States will not impose additional tariffs of 25%, or quantitative restrictions on automobile imports from Japan based on Section 232 of the U.S. Trade Expansion Act. Imposing additional tariffs or quantitative restrictions based on that law would be a very aggressive action and could be in violation of the WTO agreements.

After the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement is put into force, the two countries will determine the scope of new trade negotiations within four months. The start time and the pace of the new negotiations will be significantly affected by how the U.S.-China trade friction and the trade negotiations between the United States and the European Union (EU) play out in the future.

With respect to exports from Japan, the elimination of tariffs on auto parts, passenger cars and trucks will be priority negotiation items. However, the possibility cannot be ruled out that for strategic reasons, President Trump will defer an agreement in these sectors until the end of the 2020 presidential election. Regarding market access concerning automobiles, the joint statement issued one year ago stipulated that production and employment in the U.S. auto industry should be increased. Therefore, the United States may demand more than just the deferment of the elimination of tariffs.

As there is a provision for renegotiation on agricultural products, items not covered by the latest negotiations may be included in the scope of the new negotiations. Japanese taxable industrial products for which tariff quotas have not been allotted under the latest agreement may also be included.

In December 2018, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative announced 22 negotiating objectives for the trade negotiations with Japan. As the objectives cover most of the TPP's 21 negotiating sectors, the United States may demand liberalization in the services sectors and the inclusion of a foreign exchange provision prohibiting the practice of promoting currency depreciation.

Japan should strongly insist on the removal of the additional tariffs imposed on imports of steel and aluminum products based on Section 232 of the U.S. Trade Expansion Act. In the negotiations over the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), Canada and Mexico succeeded in persuading the United States to remove the additional tariffs.

It should also be kept in mind that under the Japan-U.S. Trade Agreement, imports from the United States will be included in the threshold amount for the invocation of the safeguard measure (emergency import restriction) for beef, making it necessary for Japan to seek an understanding from the 11 TPP signatory countries.

♦ ♦ ♦

Next, I will discuss the Japan-U.S. Digital Trade Agreement. There are vast cross-border flows of digitized data and products. Recently, due to the advance of data analysis technology and the development of artificial intelligence (AI) and robots, international competition over data accumulation has been intensifying and the digitization of production processes and the globalization of production and R&D bases have been proceeding. It is becoming more and more important to develop rules on digital trade.

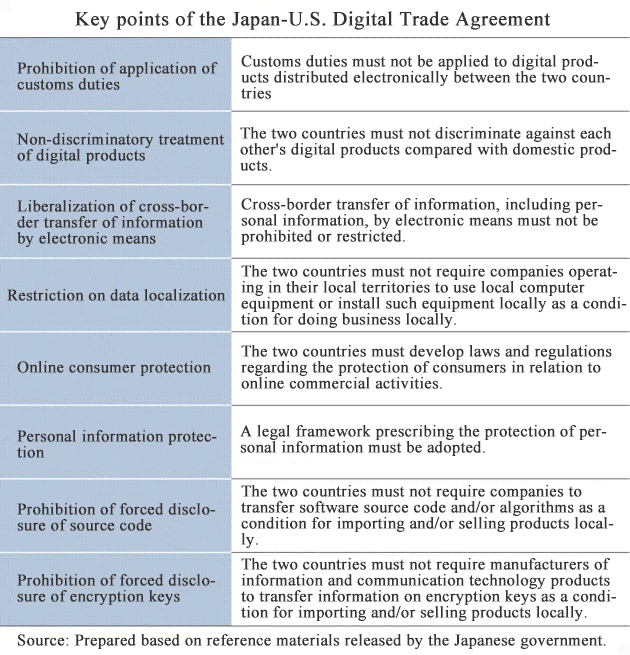

To secure its leadership in rule-making, the United States is vigorously trying to incorporate a provision concerning digital trade into free trade agreements (FTAs). The conclusion of the Japan-U.S. Digital Trade Agreement is part of this effort (see the table below).

Prime Minister Abe proposed the "data free flow with trust" concept at the Davos meeting in January 2019. The Japanese government has stated that "liberalization of cross-border transfer of information by electronic means" and "restriction on data localization," and "prohibition of forced disclosure of source code" and "prohibition of forced disclosure of encryption keys" are important for "data free flow" and for "trust," respectively.

The TPP contains an e-commerce chapter with similar provisions, but the provisions of the Japan-U.S. Digital Trade Agreement are more advanced in terms of promoting free cross-border data flow.

Although goods trade tends to attract more attention, around 40% of all Japanese companies provide data across borders (White Paper: Information and Communications in Japan, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications). It has also been reported that over the 10 years from 2005, the volume of cross-border data flow increased by a factor of 45 and that the volume will continue to increase exponentially. In the future, digital trade agreements will become much more important than goods trade agreements.

Therefore, the Japan-U.S. Digital Trade Agreement may become a critical key to the future progress of globalization. The development of rules on digital trade is most likely to become a verykey item in future FTA and WTO negotiations. Under the Japan-Europe EPA that has already been put into force, the two sides are required to conduct a review within three years to decide whether or not to include a provision concerning free data flow in the agreement.

The approach to rule-making for digital trade varies significantly from country to country. As the United States is home to huge platform providers, such as GAFA, it is supportive of the liberalization of digital trade. China is trying to secure control over data, which constitutes a wellspring of competitiveness in a digital economy, by collecting and managing data under the government's leadership. Europe attaches particular importance to data protection because of its strong concerns over privacy and personal information.

If the rules are fragmented across countries, that could impede digital trade. The Japanese government must carefully and strategically consider what kind of rules on digital trade to develop, while aiming to strike the right balance between the interests of consumers and producers.

* Translated by RIETI.

October 25, 2019 Nihon Keizai Shimbun