The Japanese economy is about to reach the end of the prolonged stagnation period due to its breakaway from deflation, the intensifying confrontation between the China-Russia camp and Western countries, and the Trump administration’s “America First” foreign policy. I would like to review Japan’s experiences during the 80 years since World War II and think about Japan’s current economic challenges.

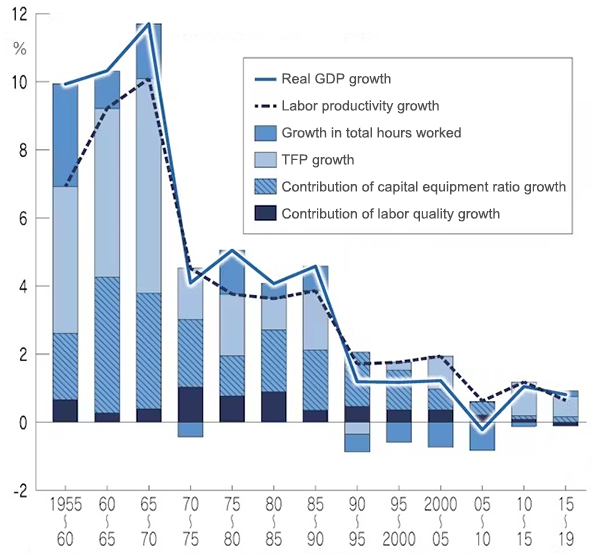

The war-devastated Japanese economy recovered so fast that its labor productivity in 1955 was restored to its 1936 level before the Sino-Japanese war. The figure below shows the results of a growth accounting analysis of the sources of economic growth as seen from the supply-side perspective in and after 1955.

The dashed line shows growth (average annual growth for each period) in labor productivity calculated by dividing real gross domestic product (GDP) by total hours worked. The combined total of the rates of growth in labor productivity and in total hours worked is equal to the rate of growth in real GDP. In the figure, the labor productivity growth rate is decomposed into the contribution of capital equipment ratio growth, the contribution of labor quality growth, and total factor productivity (TFP) growth calculated as residual.

The contribution of labor quality growth refers to growth in labor productivity through an increase in the proportion of higher-wage workers (including highly educated and regular employees) who contribute more to production. The contribution of capital equipment ratio growth includes increases in capital stock per working hour and in the proportion of some capital goods with higher contributions to production (e.g., factory machines and software are considered to contribute more than structures). TFP growth results from productivity growth through technological innovation and efficient resource allocation.

◆◆◆

As indicated by the figure, Japan had three different economic growth periods since 1955: a high growth period between 1955 and 1970, a stable growth period between 1970 and 1990, and a long stagnation period between 1990 and 2019.

During the high growth period, labor productivity growth accelerated. Average annual growth between 1965 and 1970 amounted to 10%. In 15 years, labor productivity increased 3.7-fold. Real GDP grew 4.9-fold, reflecting the fast productivity growth. Such astonishing GDP growth was unprecedented in the world. The largest source of labor productivity growth during this period was TFP growth, followed by capital equipment ratio growth per hour worked.

Of the TFP growth during this period, the manufacturing sector accounted for 57%. In the turbulent period during and immediately after the war, when Japan’s trade and investment relations with developed countries were reduced or cut off, Japan’s heavy chemical and machinery industries were left behind technologically. However, they successfully caught up with their Western counterparts through license agreements with Western companies, capital goods imports, and their own research and development. The government supported these efforts to catch up to other countries.

Wholesale and retail, and the transportation and telecommunication industries also contributed much to the TFP growth. These industries generated 37% of Japan’s TFP growth. Background factors behind their TFP growth included not only the introduction of new technologies but also the government’s proactive development of infrastructure such as ports and roads, and progress in the expansion of wholesale and retail companies.

On the other hand, 53% of capital accumulation, the second largest pillar of growth during the high growth period, came from tertiary industry. Capital accumulation in tertiary industry was attributable mainly to the shift in household demand toward capital-intensive services such as housing, transportation, telecommunications, and electricity/gas/water services, as well as the government's restraint in spending outside of infrastructure development, in effect prioritizing the still insufficient domestic savings for private sector investment.

In the 1970s, economic growth slowed. This was due to the deterioration of the terms of trade through oil crises, a lull in the machinery industry’s efforts to catch up with U.S. technology levels, the yen’s appreciation accompanying the floating exchange rate system, trade frictions with Western countries, and the end of baby-boomers’ entry into the labor market.

Even during the 1970-1990 stable growth period, however, labor productivity growth in Japan was faster than in Western countries. Its per capita GDP based on purchasing power parity was higher than in major European countries.

One reason for the high labor productivity growth was the cooperation by labor unions in emphasizing employment over wage hikes and appropriate fiscal and monetary policies that prevented Japan from plunging into stagflation (a simultaneous economic recession with severe inflation), which was seen in Western countries. Another reason was that unlike the United States where energy conservation was delayed due to oil price controls, Japan proactively promoted the development of energy-efficient technologies and the reduction of energy-intensive industries.

During Japan’s stable growth period manufacturers expanded rural production bases due to enhanced pollution regulations and labor shortages in metropolitan areas and the government’s promotion of rural infrastructure investment, so the term “rural development era” is also appropriate. The rural development contributed to TFP growth and capital accumulation across Japan. During this period, the accumulation of skills through on-the-job training and the spread of higher education progressed, with improvements to labor quality making particularly significant contributions to economic growth.

◆◆◆

In the long stagnation period starting from the 1990s, however, Japan’s economic growth remained extremely low due to a decline in the working-age population and stagnant labor productivity. Japan’s labor productivity fell to the median level among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) member countries, far behind levels in Western countries.

Some point out that Japan’s labor productivity per working-age person has not stagnated significantly. However, this view is problematic in that it does not take into account the fact that the total hours worked in Japan has increased as the employment of women and elderly people has progressed significantly since the 2010s.

The sources of labor productivity growth during this period changed dramatically around 2000. In the 1990s, TFP growth stagnated remarkably against the backdrop of the non-performing loan problem, driven by capital equipment ratio growth. In the 2000s, TFP growth recovered while the capital equipment ratio stagnated.

Some point out that the stagnation of capital accumulation is to be expected in Japan where population is declining. However, this is a misunderstanding. According to standard economic growth theory, in a developed country like Japan, capital input growth should be equal to the sum of TFP growth divided by labor share (i.e., about 1.5 times the TFP growth) and labor input growth. The sum is called natural growth.

However, capital input growth in Japan has been significantly lower than the expected figure especially since 2010. This is an abnormal situation that is not seen in any other major developed country. One possible explanation for this is the failure of companies and the public sector to substitute human labor with machinery as progress in the offshoring and the increased employment of women and elderly people made labor cheaper.

It is also necessary to note that the quality of labor in Japan has been declining in recent years for the first time since the Meiji period. This is mainly due to the fact that most women and elderly workers are employed in non-regular positions where skill acquisition is minimal.

What lessons can be learned from the postwar experience of Japan outlined above? During the high growth period, Japan focused on increasing labor productivity by supporting the introduction of new technologies and promoted rural development and human capital accumulation during the stable growth period. During the long stagnation period, however, Japan has apparently forgotten those fundamentals as it became preoccupied with escaping deflation and providing generous fiscal stimulus.

Since the end of the war, Japan has relied on free trade and security led by the United States. However, the favorable international environment is being lost. The pre-war period may provide clues regarding how to deal with this situation. For example, the government is working in earnest to reduce supply chain vulnerabilities for the first time since the 1930s.

Today’s Japan needs to learn from the failures of the 1930s when preparations for war and economic controls were the focus. As a member of the Western bloc, it must design economic security policies that respect price mechanisms and corporate autonomy.

*This paper is based on the following data and analyses in addition to the Japan Industrial Productivity (JIP) database developed by RIETI and Hitotsubashi University:

- Hitotsubashi University Institute of Economic Research, High Growth Period JIP Database

https://d-infra.ier.hit-u.ac.jp/Japanese/ltes/b000.html#07 (in Japanese) - Kyoji Fukao (2020) Japan’s Economic Growth and Stagnation in Global Historical Perspective: 1868-2018, Iwanami Shoten

- Kyoji Fukao and Tatsuharu Makino (2021) “Sources of Labor Productivity Growth in the Service Sector: An Industry-Level Empirical Analysis Using the JIP Database, 1955-2015”

Kyoji Fukao, ed., Service Sector Productivity and the Japanese Economy: Empirical Analysis Based on the JIP Database and Its Policy Implications, Chapter 2, University of Tokyo Press

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

August 13, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun