There is concern that the U.S. tariff hikes under the Trump administration will adversely affect the world economy. That said, U.S. tariff hikes will not be uniform across economies. The degree of economic impact should vary among economies in positive and negative directions alongside the magnitudes of impact.

Lesson from the first Trump administration

In 2018, the United States started to hike tariffs on impots from China and China responded by raising import tariffs on the United States. The average U.S. tariff rate on imports from China rose from 2.6% in January 2018 to 17.5% in September 2019 according to Bekker and Schroeter (2020) (Note 1). On the other hand, China’s average import tariff rate on the United States rose from 6.2% to 16.4% in the same period.

In the meantime, U.S. trade deficits with China decreased from 375.2 billion U.S. dollars (USD) in 2017 to 295.4 billion USD in 2024. That said, U.S. trade deficits with Japan and Germany remained broadly unchanged but those with Mexico, Canada, Viet Nam and others increased significantly resulting in the expansion of overall U.S. trade deficits from 792.4 billion USD to 1,202.2 billion USD.

U.S. imports from China decreased to some extent but were replaced by imports from North America, Asia and others and increases in U.S. domestic production were limited. These data clearly indicate that bilateral tariff hikes decrease bilateral trade but create trade for third-party economies due to trade diversion effects.

Keys to the second Trump administration

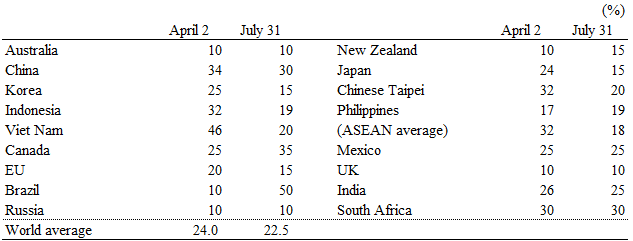

U.S. President Trump raised tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum to 50% in 2025 and imposed an additional 25% tariff on imports of motor vehicles and parts. Meanwhile, he announced reciprocal tariff rates for each competing economy on April 2. He has introduced a uniform 10% baseline tariff, and later on July 31, announced the application of lower than initial reciprocal tariffs on economies that agreed on tariff negotiations, but then imposed higher additional tariffs on China, Canada, Mexico and others as is shown in Table 1. What is important here is that the additional U.S. tariffs are varied and specific to individual economies.

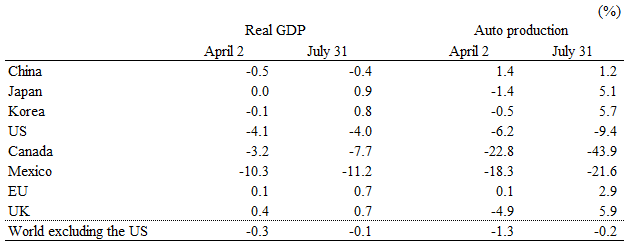

The estimated impact of the above U.S. tariff hikes on production per economy in Kawasaki (2025a) (Note 2), which used a multi-region multi-sector computable general equilibrium (CGE) model provided by Global Trade Analysis Project, is shown in Table 2. U.S. real GDP is projected to decrease by around 4%, which is larger than the annual economic growth rate. Real GDP will decrease to a limited extent in China, but the adverse impact on Canada and Mexico, whose trade dependency ratios on the United States are significantly higher than other economies, will be substantially larger than that of the United States.

On the other hand, real GDP is set to increase in the economies for which tariff negotiations with the United States have been agreed upon. Meanwhile, their motor vehicles and parts production would decrease under initial reciprocal tariffs but are set to increase under the new reciprocal tariffs. The United States will still impose tariffs on those economies but they will be lower than those imposed on other economies. Price competitiveness of those economies against other economies will improve inside the U.S. market resulting in the chance of increased exports to the United States.

As a matter of fact, Japan’s real GDP is estimated to decrease from 0.7% to 0.8% due to trade loss effects resulting from U.S. tariffs on Japan, but will increase due to trade diversion effects resulting from U.S. tariffs on China (0.6%), Canada (0.6%) and Mexico (0.3%) based on the estimated impact of U.S. tariffs by trade partner established in Kawasaki (2025b) (Note 3). With all factors taken into consideration, Japan’s real GDP will not necessarily decrease.

It must be noted that GDP measures development of domestic production, which is different from national income. Substantial decreases in production of motor vehicles and parts in North America include decreases in local productions by other economies through overseas investment. There is concern that revenues from overseas investment in those economies could adversely be affected to a substantial extent.

Appropriate economic analysis and firm behavior

Values of Japan’s exports to the United States decreased from 10 to 11% in May, June and July 2025 but that major cause for the decrease has been declining export prices. The purchasing power parity rate of the Japanese yen (JPY) in 2025 is around 93 yen for one USD in 2025 according to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook. Under the current exchange rate of JPY140 to JPY150 to the USD, Japanese firms should be able to handle a few tens of percent tariffs. As a matter of fact, real exports of goods and services in Q2 2025 increased by 4.9% y-o-y and real GDP also increased by 1.2%.

That said, there is concern of the risk of a self-generated economic downturn if economic agents, including firms, take inappropriate actions. The FY2025 white paper on economy and public finance noted that if the negative perceptions regarding the uncertainty connected to the impact of the U.S. tariff measures were to spread to economic agents, real economy would be substantially affected.

Economists are required to provide appropriate economic analysis in order to aid firms in taking effective action. The U.S. tariffs are a world-wide trade and economic agenda, but the adverse impact of the tariff hikes within bilateral relations should be the sole emphasis: as discussed above, tertiary economies benefit due to trade diversion effects resulting from multilateral relationships should not be overlooked.

August 28, 2025

>> Original text in Japanese