Life science innovation delivery

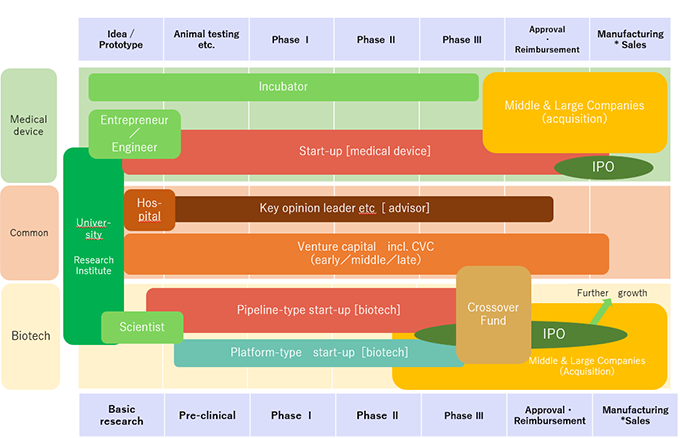

Recently, I have been researching the ideal form of business ecosystems in the field of life sciences including pharmaceuticals and medical devices. The ecosystem is characterized by the innovation delivery framework shown in Figure 1. Specifically, innovations are delivered from left to right, from academia to startups, to venture capital firms, to large companies, etc.

[Click to enlarge]

I am particularly interested in the social implementation of innovations. In the life sciences, research and development on innovations take significant periods of time before their social implementation. The life sciences ecosystem starts with scientific work to build evidence, followed by patent procedures, regulatory approval and licensing before the commercialization phase where products reach domestic and global healthcare markets. In essence, social implementation is quite far along the timeline from academia at the starting point of the ecosystem.

With these characteristics in mind, I have recently published a report (Note 1) in a reportage-style that investigates what kinds of thinking within life sciences academia (as the starting point) can effectively promote research and development toward social implementation.

In this column, I would like to focus on human resource development within the ecosystem.

Importance of human resource development as seen from interviews

This report is based on interviews with European academic stakeholders mainly in Belgium. Despite Belgium’s population of only 11 million, it has achieved a good balance of industrial accumulation and academic accomplishments in the life sciences field, with many creative approaches to learn from.

The Flanders region of Belgium is home to the research institute VIB, which has specialized in biotech since 1996. It operates under a double-affiliation model, cooperating with five universities and other institutions. When selecting research and development projects, VIB does not necessarily prioritize projects with a clear potential for social implementation. The main objective is to sharpen the science itself.

Nevertheless, VIB are able to accurately identify research and development projects that lead to social implementation. Its Technology Transfer Office (TTO) performs this function and the key is that TTO personnel are recruited from among researchers. While they provide various forms of training after recruitment, making such roles available within the career paths of researchers is a unique feature of TTO.

The VIB example represents one form of diverse career path for the researchers. Shifting to the commercialization stage after academic development, when academia produces a startup, operational and administrative personnel are naturally required. In Belgium, a program called AMBT (Note 2) was launched in 2022, including a one-year entrepreneurship program in the life sciences. While the profiles of AMBT students are diverse, 85% of the AMBT faculty members are from outside academia, providing substantial support from the business world.

While North America is the center of such human resource development, Belgium has followed suit and built a human resources development system on its own. Similar work is being done in countries like Germany and Singapore, where human resource development is progressing in line with the industrial characteristics of each country.

Key points of ecosystem formation in Japan

Since academia is at the starting point of these long-term processes, addressing social implementation within academia is a natural aspect of forming a life sciences ecosystem. This is a relatively common challenge around the world, and Japan is also wrestling with this problem. Fortunately, Japan has achieved a certain degree of globalization in the life sciences from an industrial perspective. However, it is still difficult for Japan to deploy a wide range of project support personnel in academia who are business-oriented in nature.

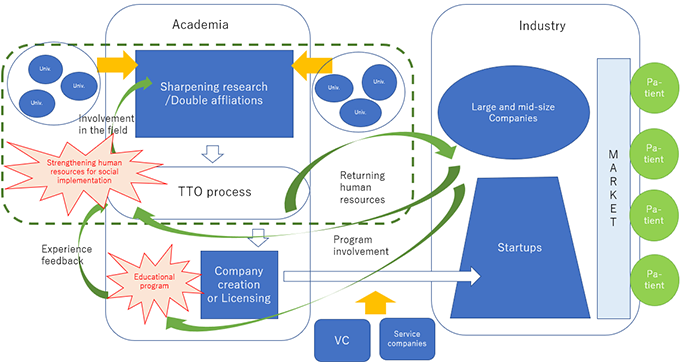

Figure 2 represents a summary of this report, illustrating and modeling several key elements in the formation of a life sciences ecosystem. The figure depicts the development of necessary human resources and their return to academia in addition to the standard approach of “sharpening research, selecting projects from a pool of research results and supporting them with human resources that are well versed in social implementation."

[Click to enlarge]

In reality, medical doctors, researchers, and businesspeople tend to prioritize their career paths in their respective organizational hierarchies. In Japan it is rare for researchers to shift into roles supporting social implementation, or for career businesspeople to pursue active involvement in entrepreneurship programs. To launch a movement pursuing social implementation from within academia, it is necessary to diversify the career paths of medical doctors, researchers, and businesspeople.

The road toward the formation of this ecosystem is not an easy one. Beyond improving productivity, creating an environment where individuals feel they have such career options may be one of the ultimate goals of forming such ecosystems. Many conversations with various people since publishing the report have only strengthened this impression.

July 25, 2025

>> Original text in Japanese