2025 as a Milestone

2025 is a pivotal year for healthcare and nursing care in Japan as a large percentage of the baby boomer generation will become 75 years or older, and the elderly proportion of the population will increase significantly. Over the past 20 years or so, this fact has motivated calls to develop systems to provide adequate healthcare and nursing care services.

Specifically, since around 2005 there have been numerous studies and discussions regarding such systems and potential costs targeting 2025 (by the Working Group on Services and Security [Healthcare, Nursing Care and Welfare] under the National Social Security System Reform [September 2008]). At the same time discussions have progressed on the appropriate development of the healthcare system and following the enactment of the Act on Amendatory Law to the Related Acts for Securing of Comprehensive Medial and Long Term Care in the Community (2014), prefectural governments have been required to formulate plans for regional healthcare (Note 1) with 2025 as the target year.

The regional comprehensive care system, on which discussion started around 2003, has also come to play an important role. The regional comprehensive care system is defined as a “system in which an integrated set of housing, healthcare, nursing care, preventive medicine and living support services are provided, allowing people to continue to live independently through the end of their life in the communities that are familiar to them even if they come to require intensive nursing care, with a target of 2025” (source: the website of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [MHLW]).

As the national government has provided generous support for a shift toward healthcare and nursing care at home through the adjustments of medical and nursing care service fees, the share of healthcare and nursing care services provided at home, which form the core of the regional comprehensive care system, has increased to a certain degree. (Note 2) As medical service fees have repeatedly been revised to encourage the shortening of hospital stays, patient attitudes toward healthcare and nursing care have changed significantly.

Regarding hospitals, with the increase in the elderly population, the number of new inpatients has risen, and the share of people aged 65 or older among the total number of inpatients came to 74.8% in 2020 (Note 3) (however, it should be noted that the estimated number of inpatients itself has continued to decrease since 2005).

Where do elderly, dependent patients go after being discharged from hospital? They enter nursing care facilities or receive care at home, including both medical and nursing care services. In the case of nursing care, the number of long-term nursing care insurance beneficiaries has continued to rise and the annual cumulative number of people receiving nursing care services has increased at an even faster pace. (Note 4) This indicates an increase in the frequency of use of nursing care services, which is a factor behind the chronic shortage of nursing care workers.

Management conditions of hospitals and nursing care facility management companies

From the perspective of hospitals and nursing care providers, this trend can be seen as a change in demand, so how has the profitability of hospitals and nursing care providers changed?

The profitability of hospitals has been declining since before the COVID-19 pandemic. While revenue has been growing, many categories of hospitals have become unprofitable (on a pre-subsidy basis), mainly due to increasing shares of pharmaceutical and outsourcing costs. (Note 5) The main expense of hospitals is personnel, which accounts for between 40% and 60% of the revenue. However, the personnel cost has remained stable since 2015 when hospitals entered the current period of low profitability. Hospitals have been managing operations by increasing medical staff numbers to handle the increasing inpatient population while controlling for costs in order to avoid excessive deficits.

On the other hand, nursing care is divided into two categories—facility-based care and home care. In facility-based care including nursing homes, there are limited numbers of unprofitable facilities. (Note 6) Nonetheless, despite an increase in the number of patients, profitability has been declining due to revisions in nursing care service fees.

The profitability of home care services, including visiting care, day care, and visiting nursing has until recent years remained at a certain level, supported by an increase in the number of patients. (Note 7) However, as greater use frequency increases profitability, a significant burden is placed on the staff, so this may not necessarily be a sustainable situation.

What can and cannot be adjusted in response to changes in demand for healthcare and nursing care services

Capital formation is critical for managing a hospital or a nursing care institution, and maintaining a sound balance sheet is critical for undertaking capital investments (investment in equipment), beyond simply operating at a profit or loss. From that perspective, it is difficult to change the number of facilities in line with changes in demand. To make large-scale investments such as those for reconstruction, it is necessary to minimize the debt resulting from past capital investment, among other expenditures, but this is difficult when profitability is low. That is one reason why it is difficult to adjust the stock of facilities in line with demand.

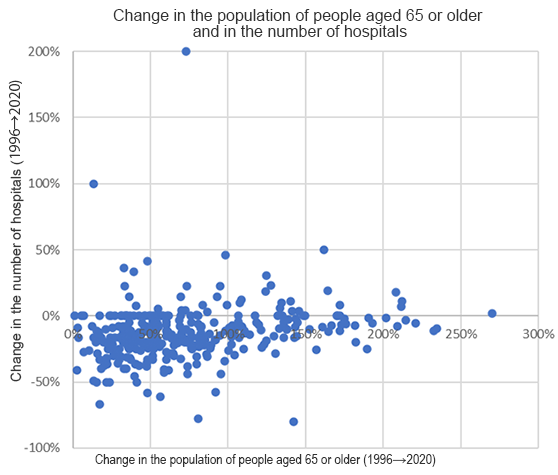

Figure 1 shows the rates of change in the population of people aged 65 or older and change in the number of hospitals in the secondary healthcare areas (nationwide, 330 secondary medical regions were designated to ensure that a full complement of general in-hospital healthcare services, including emergency care, can be provided to the population) (Note 8). The trend since the mid-1990s illustrates the difficulty of maintaining an appropriate relationship among these factors.

However, if Japan’s healthcare and nursing care systems were truly disconnected with changes in demand, the systems would have faced a very severe situation.

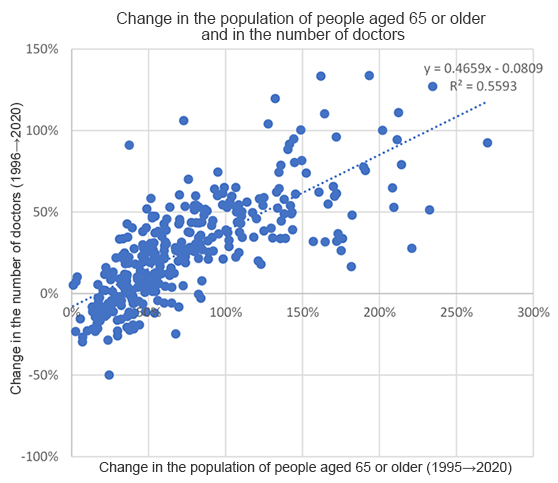

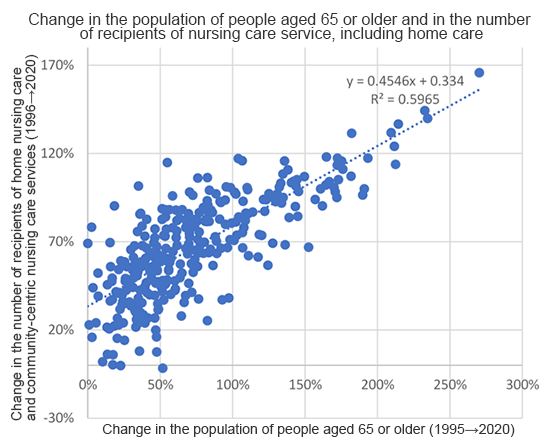

Figures 2 and 3 below indicate that this is not the case. The figures plot the rates of change in the population aged 65 and older against the change in the number of doctors and change in the number of people receiving nursing care service, including care at home (the latter represents the trend in the period since the mid-2000s and has been reorganized based on the medical regions despite nursing care typically being unrelated to the medical region concept).

As is clear from Figures 2 and 3, the healthcare and nursing care systems have changed in line with demand to some degree over the medium to long term. Hospitals have adapted to the demand situation by making adjustments to institutional systems and organizations while maintaining their facilities. With respect to nursing care, the data reflect the changes in the number of patients, with the number of patients correlating to the change in the elderly population.

However, areas with high availability of doctors and those with well-developed nursing care systems do not necessarily overlap. The situation varies from region to region. The Tokyo Metropolitan Area does not have an outstanding advantage in both the healthcare and nursing care sectors. There are cases where the second or third largest city in a prefecture has been the most successful in securing doctors or creating a well-developed nursing care system.

Complimentary insight for Developing Post-2025 Systems

The Post-2025 Vision of the Healthcare and Nursing Care Systems includes an appendix to the Basic Policy for Comprehensively Securing Regional Healthcare and Nursing Care which was revised last year, which states that “in order to meet the growing needs for healthcare and nursing care with limited human and other resources, aiming for optimization and efficiency in the delivery of medical and nursing care services is also important (Note 9).”

In order to put that viewpoint into practice, it is necessary to consider factors such as the medium- and long-term trends in the availability of doctors and nursing care workers and whether hospital and care facility management companies can endure changes in the healthcare and nursing care systems from the viewpoint of profitability, while taking into account the fact that changes in the number of hospitals and demand for healthcare are not necessarily correlated. As is clear from Figures 2 and 3, the healthcare and nursing care systems continue to change in response to the revisions of healthcare and nursing care fees. To avoid confusion in a post-2025 society, when growth in the elderly population is expected to peak in more and more regions, it will become increasingly important to consider the balance of healthcare and nursing care in each region in determining how to respond to such changes.

This issue should not be handled only by the people involved in the provision of healthcare and nursing care, but also by those who support them. For example, end-of-life care will become more and more important (Note 10), and where to provide such care is a question that requires providing various support options that are suited to the respective characteristics of individual regions, rather than merely relying on care service companies.

This is not limited to end-of-life care; the role of digital transformation (DX) in promoting regional comprehensive care is important. To ensure that regional comprehensive care can function effectively in practice, it is necessary to consider how to effectively share information among medical professionals involved in healthcare and nursing care, including doctors, nurses, and nursing care workers. The role of an information hub in each region and determining how to improve the quality of healthcare and nursing care in each region will vary. It is essential that service providers also share the viewpoint of what should be achieved by utilizing DX.

Ensuring fairness and advancing in accordance with the working styles and perspectives of healthcare and nursing care workers is essential. At the same time, stakeholders should assess the developments in the demand and supply systems while providing support, to ensure that the “post-2025” transition is achieved as smoothly as possible.

December 13, 2024

>> Original text in Japanese