I believe that some readers may have had the experience of resenting their workplace or losing the motivation to work because they were assigned undesired tasks and, as a result, wasted working hours looking at social media sites or checking private emails. In order to enhance productivity within a firm, it is essential to keep workers motivated and control moral hazard behavior (shirking) by providing an appropriate working environment. As employers are unable to fully observe workers’ behavior in the workplace, in many cases the collective performance of a team or division is taken into consideration in determining the amount of compensation or other remuneration for individuals. However, as was argued by Alchian and Demsetz (1972) and Holmstrom (1982), under such a revenue-sharing arrangement, workers feel tempted to avoid hard work by free-riding on their colleagues’ contributions to the workplace. This column introduced readers to the findings of a research paper co-authored by the author and Professor Markussen at the University of Copenhagen (Kamei and Markussen, forthcoming). This paper experimentally shows that low productivity and moral hazard behavior, such as shirking, are prevalent among workers assigned with “undesired tasks” (externally imposed tasks that they do not enjoy). At the same time, this paper proposes that worker participation in the process of task assignment is effective in mitigating the negative effects of mismatching between task preference and task assignment.

Experiment Design

A laboratory experiment makes it possible to show a causal relationship with a high degree of validity (Note 1). Our experiment was conducted in the Laboratory for Experimental Economics of the University of Copenhagen in 2018 and 2020. A total of 601 students participated in the experiment as subjects.

417 of the 601 subjects participated in the experimental sessions where a team-based remuneration system was used. In these sessions, the participants were randomly divided into teams of three, with each team assigned either an “addition” task or a “counting” task, and then the team members individually worked on the task assigned to their own team for 30 minutes. Two treatments were designed. In one treatment condition, one of the two tasks was randomly assigned to each team. In the other treatment condition, the task assignment was made by a majority vote among the three team members. The remuneration was based on revenue sharing: each team member received a third of the total earnings generated by the task-solving activities in the team.

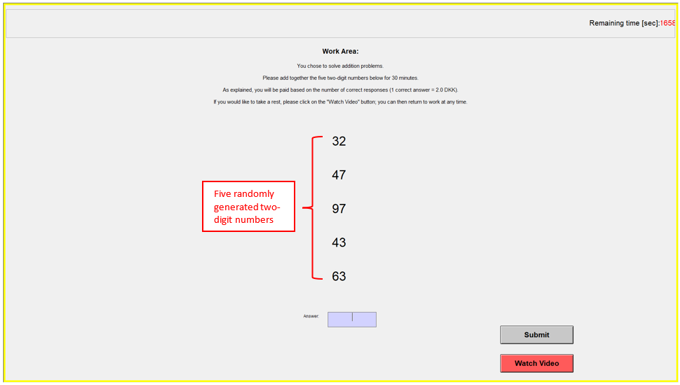

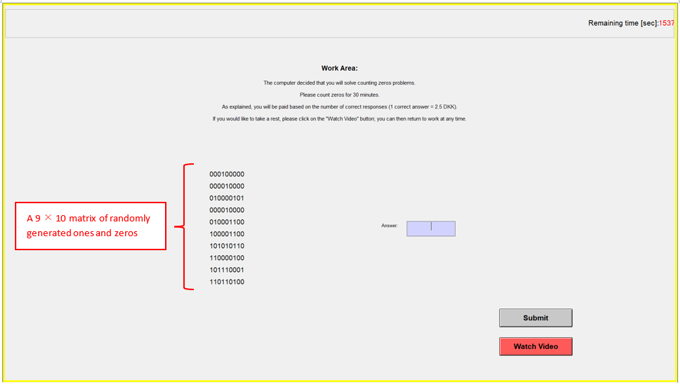

Figure 1 shows an example of a computer display on which the subjects performed their tasks. In the addition task, subjects were shown five two-digit numbers and had to calculate the sum (Figure 1.A). Each question (five numbers) was randomly generated by the computer. Each correct answer was rewarded two Danish kroner (the yen-kroner exchange rate at the time of the experiment was around between 16.5 yen and 17.5 yen/kroner). In the counting task, subjects were provided with a 9 × 10 matrix of randomly generated ones and zeros and had to count the zeros (Figure 1.B). Each correct answer was rewarded 2.5 Danish kroner. For both tasks, the total amount of remuneration in a given team was determined in proportion to the number of correct answers in the team. The subjects could answer any number of problems within the 30-minute task period.

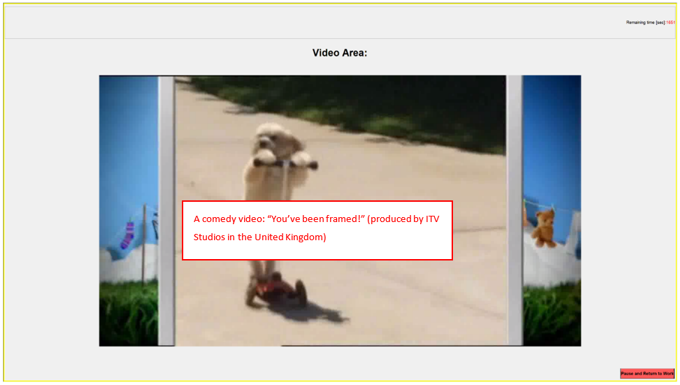

During the experiment, the subjects were also given the option of privately watching a funny video clip (the British “You’ve Been Framed!” show) - see Figure 1.C. In short, the subjects had the choice of working or shirking during the task-solving period. Video watching is treated as a measure of shirking in this study.

For the purpose of comparison with worker behavior under team-based remuneration (revenue sharing), we conducted another experiment sessions in which the subjects solved the tasks under individual-based remuneration (pay based on individual performance). Of the 601 subjects, 184 participated in these experiment sessions. Notice that unlike individual-based remuneration, under the team-based remuneration, team members have incentives to free ride on other members’ contributions because their own remuneration depends not only on their own performance but also on the others’ performance.

In order to analyze the effects of (mis)matches between workers’ task preferences and task assignment, before starting the experiment we elicited preferences from all subjects as to which task they would like to work on.

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

Mismatching between Task Preference and Task Assignment Undermines Performance and Leads to Free Riding

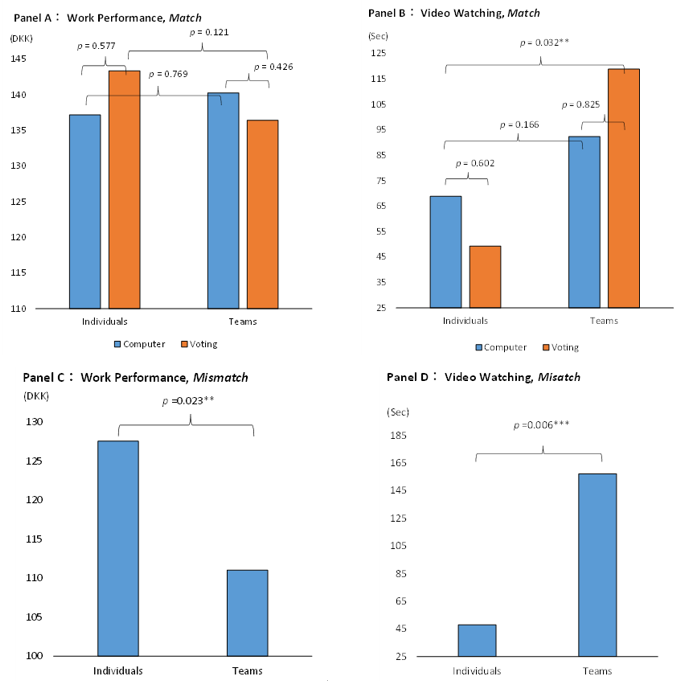

The important indicators of worker behavior in this experiment are (a) work performance, measured by the earnings generated from task solving, and (b) shirking, measured by the duration of video watching. Figure 2 shows the average levels of these two indicators for those assigned to solving tasks they want (Panels A and B) and those assigned undesired tasks (Panels C and D). The blue bar indicates the average worker behavior when the computer randomly determined task assignment, while the orange bar indicates the average worker behavior when the voting outcome determined the task assignment. The figure also shows the data sorted by whether the subjects were paid according to the individual-based remuneration (“Individuals”) or the team-based remuneration (“Teams”).

Notice that the material incentive to work is reduced to a third under team-based remuneration (revenue sharing) compared with individual-based remuneration (performance pay) as the team size is three in this experiment. Reflecting the difference in the incentive, teams watched the video for longer than individuals (Panels B and D). However, shirking was more prevalent among those who were assigned their undesired tasks (Panel D). As a result, when task assignment did not match preferences, workers in teams solved significantly fewer tasks than individuals (Panel C). In stark contrast to that finding, the effects of team-based remuneration were insignificant for work performance when they were assigned their desired tasks, regardless of the treatment (Panel A).

In the individual treatment, preference mismatching did not worsen video watching (Panels B and D). However, the mismatching undermined work performance by more than 10 Danish kroner—or more than around 170 yen at the exchange rate at the time of the experiment (Panels A and C). As will be explained later, the mismatch between the workers’ skills and the assigned tasks among those assigned undesired tasks causes this difference.

In sum, the above findings underline the importance of taking into consideration workers’ task preferences when assigning their work. If workers are forced to work on undesired tasks, their work motivation suffers due to problems such as negative reciprocity and task-skill mismatching, raising the risk that unproductive activities, including shirking, may become endemic, particularly under a team production system.

[Click to enlarge]

Giving Organization Members Task Choice Increases Productivity

Kamei and Markussen (forthcoming) quantitatively showed that the negative effects of mismatching, which are clearly indicated by Panel C in Figure 2, are attributable to two effects. The first one is a behavioral effect that cannot be explained by standard economic theory (e.g., self-interest). As was explained earlier, this appears in the form of an unproductive phenomenon, such as workers resorting to shirking (video watching), due to a decline in work motivation caused by negative reciprocity arising from the assignment of an undesired task—that is, a psychological reaction against the assignment of the task.

The other is a selection effect. According to the experiment data, on the whole, workers wish to be assigned tasks suited to their skills. This means that assigning tasks to workers contrary to their preferences leads to mismatching between the workers’ skills and the assigned tasks, resulting in a decline in productivity. The observed strong correlation between a decrease in the time spent performing tasks (Figure 2.C) and a decline in work performance (Figure 2.D) among those assigned undesired tasks is attributable in large part to the effects of mismatching between the workers’ skills and tasks assigned. The negative effects of skill-task mismatching were particularly conspicuous with regard to the addition task. Given that the addition task requires better arithmetic skills than the counting task, the finding suggests that the selection effect is particularly important for tasks requiring specific vocational skills.

The simplest way of overcoming the negative effects of mismatching is to allow workers themselves to choose which tasks to perform in the firm. By giving individuals a task choice, or, in the case of a team production system, by allowing team members to make decisions on projects and other matters by majority vote or other democratic processes, the consequences of mismatching can be mitigated, with the abovementioned two behavior effects avoided. There is another behavior effect, which was not quantitatively verified in our experiment. When workers are allowed to choose tasks themselves, it may bring a “democracy premium” to worker behavior. A democracy premium refers to a behavior effect that democratic decision-making directly has on people’s behavior, say, by increasing their intrinsic motivations to cooperate (e.g., Deci and Ryan, 1985). Dal Bó et al. (2010) and Kamei (2016) argue that a democracy premium has extremely strong effects under a situation of social dilemma. According to the argument, having workers involved in task assignment within an organization is not only effective in correcting mismatching but also desirable from the viewpoint of creating intrinsic motivations, and may therefore have a positive impact on productivity improvement.