1. Introduction

The role of standardization has expanded from the traditional specification of technologies related to production processes and product appearance to design specifications (e.g., pictograms) related to public safety and ICT services used to transfer information (Note 1) [1, 2, 3]. Therefore, a quantitative understanding of the relevant activities of companies and others is important for policymaking.

This article presents the key findings of a survey I conducted on standardization activities undertaken by companies and others during 2019 [4]. The survey covered standardization activities within institutions; the survey population consisted of Japanese institutions, including companies and research institutes. The survey aimed to gain useful insights into the administration of standardization activities by understanding how and to what extent companies and other organizations implement standardization activities.

This survey is the third in the series, following surveys for 2017 and 2018 [5, 6]. This year’s survey included a new item on governance related to the disclosure of R&D information in standards development organizations (SDOs). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first relevant survey that focuses on this issue.

The previous studies were conducted on an ongoing basis. By comparing the results of each year's survey, approximate yardsticks were obtained for items such as the degree of standardization activities and the development of organizations related to standardization activities (Note 2).

The survey operation adopted an electronic method for the deliberation and collection of results in addition to the conventional postal system. As the survey supervisor, I contacted each survey target directly through postal mail. The survey was conducted between April and mid-July 2021 (Note 3). The survey targeted institutions that had sales of 10 billion yen or more when the survey initially started and that had responded to either of the two previous surveys.

2. Results

2.1. Degree of Standardization Practice

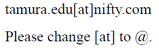

Table 1 shows the number of institutions conducting standardization activities. Of the respondents, 67% (62 cases) indicated that they are implementing standardization activities. This number is almost the same as the 62% (78 cases) in the previous survey. A comparison of previous results shows that the rate of undertaking standardization activities is similar in both years [4, 6].

Source: Tamura, S. (2021) [4]

2.2 Organizational Design for Standardization Activities

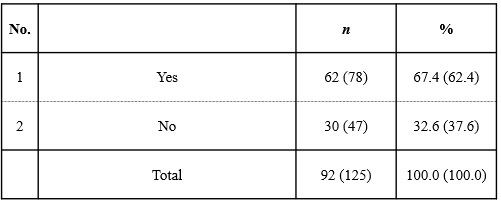

Regarding developing an organization to oversee standardization activities, 33 respondents (approximately 40%) answered that they had developed such an organization (Table 2). As for the percentage, the result is similar to that of the previous year (42.6%). These results are generally similar to those obtained in the past three years, indicating that developing organizations for standardization activities have progressed to a certain degree.

Source: Tamura, S. (2021) [4]

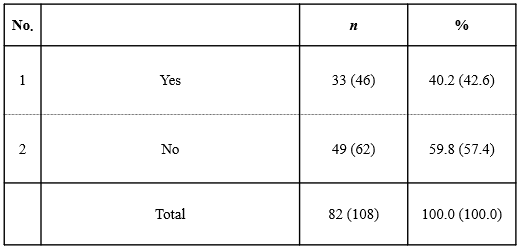

2.3. Reasons for not Implementing Standardization Activities

The reasons for not implementing standardization activities, which are considered important from a policy perspective, were surveyed. The most common reasons were that standardization activities were unnecessary for marketing their products and services, and that they employed established standards instead of formulating new standards (42.9% each). This outcome implies that engagement in new standardization efforts is considered unnecessary if related standards have been established in the market for related technology. In some cases, standardization is not necessary for the marketization of the technology. The most selected items were the lack of an organizational structure for implementation and the lack of human resources for implementation" (14.3% each). These items are mainly related to the organizational managerial capacity and resources. To implement this strategy, an internal organization is required [7]. It has been shown that managerial capacity needs to be improved to implement standardization activities.

Source: Tamura, S. (2021) [4]

2.4. Types of Standardization Activities

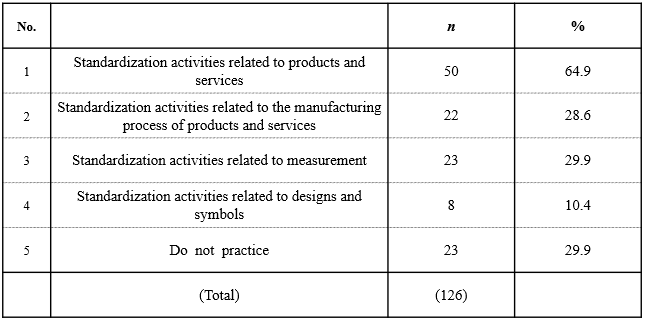

Among the activities implemented, standardization activities related to product specifications and manufacturing methods were the most common (64.9%), followed by measurement (29.9%) and manufacturing processes (28.6%) (Table 4). Activities related to design and symbols accounted for 10.4% (multiple possible responses). The trend in the types of standardization activities implemented was similar to that of the previous year. Standardization related to product standards can be understood as the standards for goods and services. Conversely, standards related to manufacturing methods can be understood to include standardization related to the manufacturing process for providing one's goods or services, and standardization when the goods or services to be produced are related to the manufacturing process. The outcome shows the fact that there is a certain degree of standardization activities related to designs and symbols, as in the previous findings [6]. This fact may imply that standards for designs and symbols (e.g., pictograms for emergency exits) are necessary for building social systems (Note 4) [6].

Source: Tamura, S. (2021) [4]

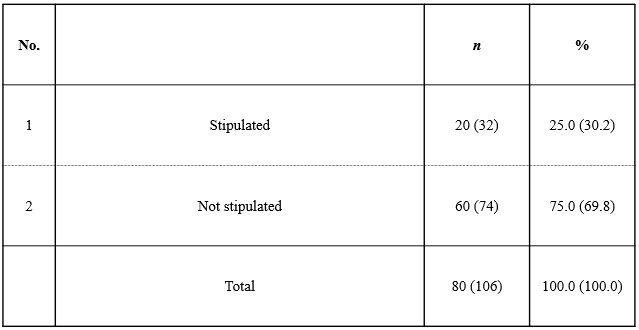

2.5. Establishment of Guidelines for Standardization Activities

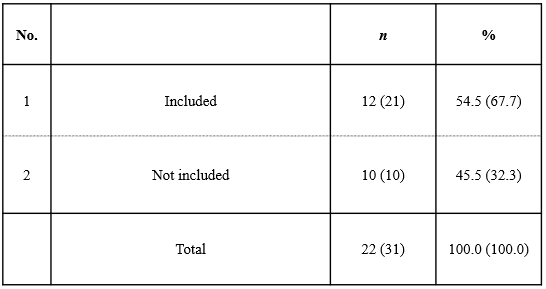

Approximately 20% of the respondents developed institutional management guidelines for standardization activities (Table 5). About 55% of the surveyed institutions that developed guidelines indicated that their management guidelines for standardization activities include a separate section on trade secret protection (Table 6). Both results show survey figures similar to those of the previous year's survey results. The results confirm the findings of the case study analysis in a previous study [8].

Source: Tamura, S. (2021) [4]

Source: Tamura, S. (2021) [4]

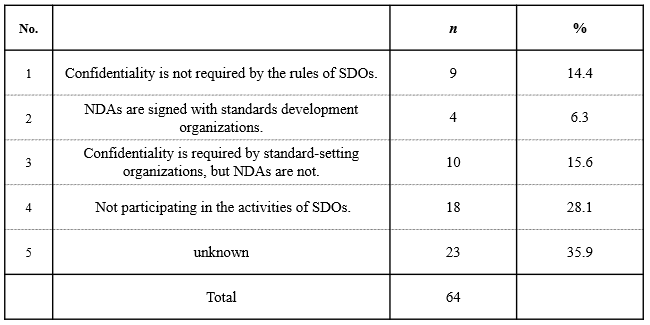

2.6. R&D Information Management in Standardizing Organizations

It is an important policy issue to develop a system that allows participants to conduct the standardization that they desire while maintaining the confidentiality of their research results. This survey is conducted on the administration of internal information in standards development organizations (SDOs), where standardization activities are conducted. The results suggest considerable differences among organizations, ranging from those that take virtually no action to those that do to some extent. In standardization activities, each participant must disclose the technical content they intend to standardize. For example, it is similar in some aspects to the activities of academic societies in which academic results are presented. However, concerning presentations at academic conferences, from the perspective of protecting the authorship of research results in academic fields, issues such as plagiarism are considered research misconduct and are subject to various academic and social sanctions. The operations of academic societies and related academic systems are developed based on these common rules. Conversely, the handling of research information in SDOs does not appear to be well-developed.

Prior studies have indirectly analyzed the externalities of information leakage associated with standardization activities (discussed in the context of the benefits to users of the information obtained). However, from a different perspective, these externalities can be seen as indirect evidence of the leakage of relevant research-related information [9, 10, 11].

3. Summary

Since this investigation was the third survey conducted in this series, it was possible to compare the data obtained from the previous two surveys to indicate the approximate validity of the figures for the main items [4, 5, 6]. From an academic point of view, this outcome means that I was able to compile data with a certain degree of success. The percentage of companies and other entities implementing standardization activities was approximately 60% (Table 1). In addition, the percentage of companies that established standardization organizations was approximately 40% (Table 2).

During this survey, a new questionnaire on the governance of R&D information was conducted, revealing differences among SDOs in handling information disclosure. Since information disclosure in SDOs is an unavoidable part of standardization activities, participants are required to manage information leakage, and SDOs must also establish a management system to cope with this issue. In addition, SDOs must disclose information to the public and participants regarding the status of the systems they have in place for confidentiality. This treatment is important for the implementation of standardization activities [4, 11].

Finally, I, as the survey administrator directly contacted target respondents to provide them with the survey and responded to inquiries about how to answer it. I provided information to respondents through this survey and had the advantage of obtaining two-way communication with them. Moreover, I also obtained a fairly high response rate (above 50%). I want to take this opportunity to thank those who were asked to respond to the survey despite the restrictions on activities as responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of this survey have been provided to the Japan Industrial Standards Committee (JISC), relevant departments of the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), the Japanese Standards Association (JSA), international institutions (ISO, IEC, and OECD), and others to establish a system that enables international comparison of key indicators that were observed in this survey, such as the implementation rate of standardization activities (Note 5).

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere appreciation to those who made time to respond to survey requests despite their busy schedules and to all those who cooperated in responding to the survey. The study was supported by JSPS Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15K03718 and 19K01827; Principal Investigator: TAMURA, Suguru).

Because this remark is important academic information, the JSPS granting policy is appended as follows. “The views and responsibilities regarding research results resulting from a grant shall exclusively belong to the researcher; the implementation and publication of said research results are not based on requests from the Japanese government body that provides the grant or others. Namely, the research funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research shall be conducted under the individual researcher’s authority with the researcher’s awareness and responsibility. ” (Handbook on Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research Program [Japan Society for the Promotion of Science] [in Japanese]) (Note 6).