Continuing Inbound Tourism Boom: Japan’s Growth Second Highest among the OECD Countries

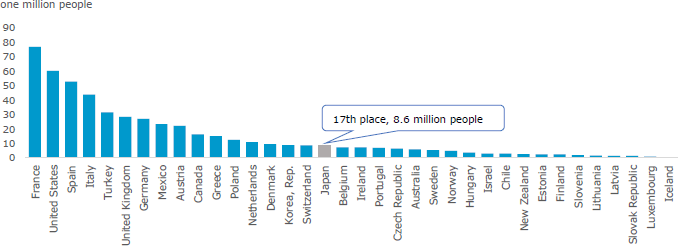

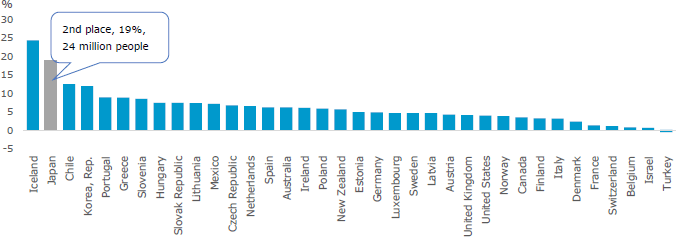

Over the past several years, the number of foreign tourists visiting Japan has continued to rise, achieving new record highs. As was pointed out in a column by Konishi (2016, [1]), foreign tourists have become attracted to Japan mostly because of efforts made by the country with respect to tourism promotion, such as the relaxation of visa requirements, and the development of transportation infrastructure, as well as fortuitous external factors, including the weak yen, the low crude oil price, and the economic growth of other countries. First, in order to identify the current state of inbound tourism in Japan relative to the situations in the rest of the world, I will conduct an international comparison of the recent situation based on World Bank Open Data (2018, [2]). Figure 1 shows a ranking of the 36 OECD countries in terms of the number of inbound tourists in 2010. Japan placed 17th, with around 8.6 million inbound tourists. The top four countries were France, the United States, Spain and Italy. Figure 2 shows a ranking of countries in terms of the compound average growth rate (CAGR) of the number of inbound tourists between 2010 and 2016. Japan, for which the number of inbound tourists increased with a CAGR of around 19% to 24 million people, placed second, after Iceland. Those two figures make it clear that Japan has achieved substantial growth as a tourist destination compared with 2010, when the number of inbound tourists was very low by the global standard. According to the results of the most recent survey by the Japan National Tourism Organization (JNTO) (2019, [3]), the number of inbound tourists in Japan in 2018 was around 31.19 million people, indicating that Japan has continued to grow as a tourist destination in 2016 and later. Which regions in Japan are preferred by foreign tourists as their location of stay?

Is Attractiveness as a Tourist Destination a Constant?—Insight from the Tourist Destination Ranking List

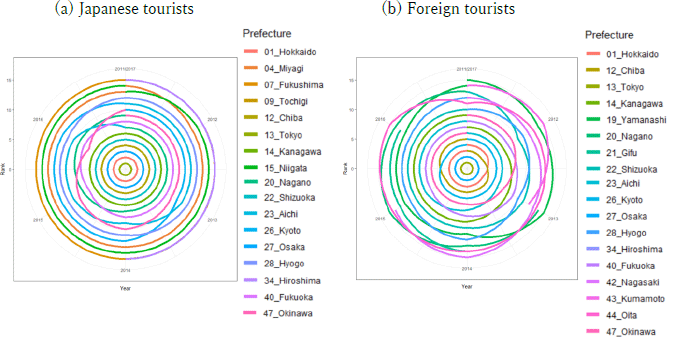

If a region's attractiveness as a tourist site is a property that is developed over a long period of time through the combination of multiple factors, including climate, geographical features, and culture, and if the evaluation of the attractiveness is absolute, the ranking of tourist destinations is likely to remain relatively constant and change little. Figure 3 shows changes in the rank of the top 15 prefectures in terms of the numbers of domestic and foreign tourists between 2011 and 2017 based on the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism's Accommodation Survey. The changes are expressed in the form of Batty's rank clock (2006, [4]). If the top 15 ranking remains unchanged in terms of both the lineup and order, 15 concentric circles are drawn, with each circle expressed in a single color. The innermost circle represents the most popular tourist destination, and the outermost circle represents the least popular one. The time axis for the observation period starts at the top of the circle (12 hour position of the clock) and proceeds clockwise. The rankings in the first and last years of the period, 2011 and 2017, can be compared at the 12 hour position. For domestic tourists, the top six tourist destinations remained unchanged during the observation period. In 2014 and later, the order of the bottom half of the top 15 also remained unchanged.

Meanwhile, for foreign tourists, Tokyo and Osaka continued to be the most popular and second most popular tourist destinations, respectively. Otherwise, there were frequent changes in the positions among the top 15. In addition, there were frequent new entries and exits from the top 15, resulting in the presence of many imperfect circles.

The ranking of popular tourist destinations for domestic tourists remained relatively stable during the observation period. In other words, for domestic tourists, a regions' attractiveness as a tourist destination is a relatively constant feature. However, for foreign tourists, the attractiveness of tourist destinations are temporary and may change in a short period of time.

In short, tourists’ preferences change and there is room for regions to make efforts to become more popular as tourist destinations. Domestic tourists favor prefectures in the Tohoku and northern Kanto regions as tourist destinations, while of the prefectures in the Kyushu district, only Fukuoka and Okinawa are included in the top 15 popular destinations. In contrast, for foreign tourists, no prefecture in the Tohoku or northern Kanto regions is included in the top 15 popular destinations, while all prefectures in the Kyushu region except for Miyazaki and Kagoshima are included.

[Click to enlarge]

Which Regions Are Growing as Tourist Destinations For Inbound Tourism?

According to Konishi and Nishiyama (2019, [5]), with respect to domestic tourism, little change has occurred in terms of both the ranking order of tourist destinations (Figure 3) and the number of domestic tourists, which increased only 0.11% during the observation period on a CAGR basis. Meanwhile, with respect to inbound tourism, the number of foreign tourists grew 25.2% on a CAGR basis. Let us look at which regions grew as tourist destinations. Table 1 shows the growth rates of the total number of overnight-stay foreign tourists for popular tourist destinations on a CAGR basis (2011-2017). The top five are Kagawa, Saga, Nara, Aomori, and Kagoshima Prefectures, in that order. I assume that for most Japanese-based readers, these regions are not familiar as tourist sites. That is quite natural given that in terms of the number of domestic tourists, the growth rate is negative for Kagawa, Saga and Aomori Prefectures and is positive but lower than 1% for Nara and Kagoshima Prefectures. In terms of the number of tourists who stayed overnight, the ranking positions of the four prefectures other than Kagoshima fell during the period. Three of the five prefectures are near the bottom of the ranking. To put it simply, these regions are not popular as the location of stay among domestic tourists. On the other hand, the top four prefectures in terms of the number of foreign overnight-stay tourists recorded a rise of more than 10 positions on average during the period. As part of its effort to promote tourism, Kagawa Prefecture, for example, holds the Setouchi International Art Festival every three years and provides tourist information via a multi-language website. Saga and Aomori Prefectures have become popular as locations for movies and TV shows. Currently, around 40% of all foreign tourists visit the Kansai region, and Nara Prefecture is capturing this demand. As Kagoshima Prefecture abounds in tourism resources, including Yakushima Island and hot springs, its ranking position was the same in terms of the numbers of both foreign and domestic tourists.

| Ranking in terms of the growth rate of the number of inbound tourists | Prefecture | Inbound tourists | Domestic tourists | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAGR | Change in the ranking position in terms of the number of tourists (2011-2017) | CAGR | Change in the ranking position in terms of the number of tourists (2011-2017) | ||

| 1 | Kagawa | 50.2% | 34→22 | -0.1% | 39→42 |

| 2 | Saga | 48.2% | 35→25 | -0.8% | 45→45 |

| 3 | Nara | 45.4% | 39→28 | 0.6% | 46→47 |

| 4 | Aomori | 43.5% | 38→29 | -0.2% | 30→28 |

| 5 | Kagoshima | 37.4% | 20→18 | 1.0% | 20→18 |

Chance for New Tourist Spots to Emerge

Locations of overnight stays for foreign tourists in Japan in recent years have been concentrated in major cities in the Kanto and Kansai regions that form the so-called golden route. However, due to an increase in repeat visitors and the diversification of information sources, including social network sites (SNS), we have recently observed the dispersion of the flow of tourists and an increase in the number of tourists to regions which were previously not frequented by tourists. It has also become clear that the number of foreign tourists is increasing in regions that are not perceived by Japanese people to be popular tourist destinations. Of course, some regions popular among Japanese tourists are also favored by foreign tourists, as shown by Figure 3. Kyoto Prefecture is being shunned by domestic tourists who want to avoid the congestion resulting from the inbound tourism boom, resulting in a decline in the number of tourists who stay overnight (March 4, 2019, issue of The Kyoto Shimbun, [6]). Congestion is one of the negative effects of an increase in tourists. A desirable scenario is that regions not frequented by domestic tourists will attract attention from foreign tourists as new tourist destinations, resulting in the diversification of locations for overnight stays and easing of congestion. If a virtuous cycle starts, with new tourist sites discovered by foreign tourists growing further and attracting domestic tourists, then tourism will become a major local industry. In 2011, foreign tourists accounted for only 5% of the total number of overnight-stay tourists, but their share is more than tripled to 17% in 2017. If the number of foreign tourists continues to increase and if they continue to search for new places to visit, new tourist spots could be created in Japan and tourism could become a lively industry in more prefectures, widening the range of tourism options for domestic Japanese tourists as well. I would be most pleased to see that scenario being realized.